The Legacy Project: Preserving and Engaging the Digital Archive of the Colombian Truth Commission

Damien Rea

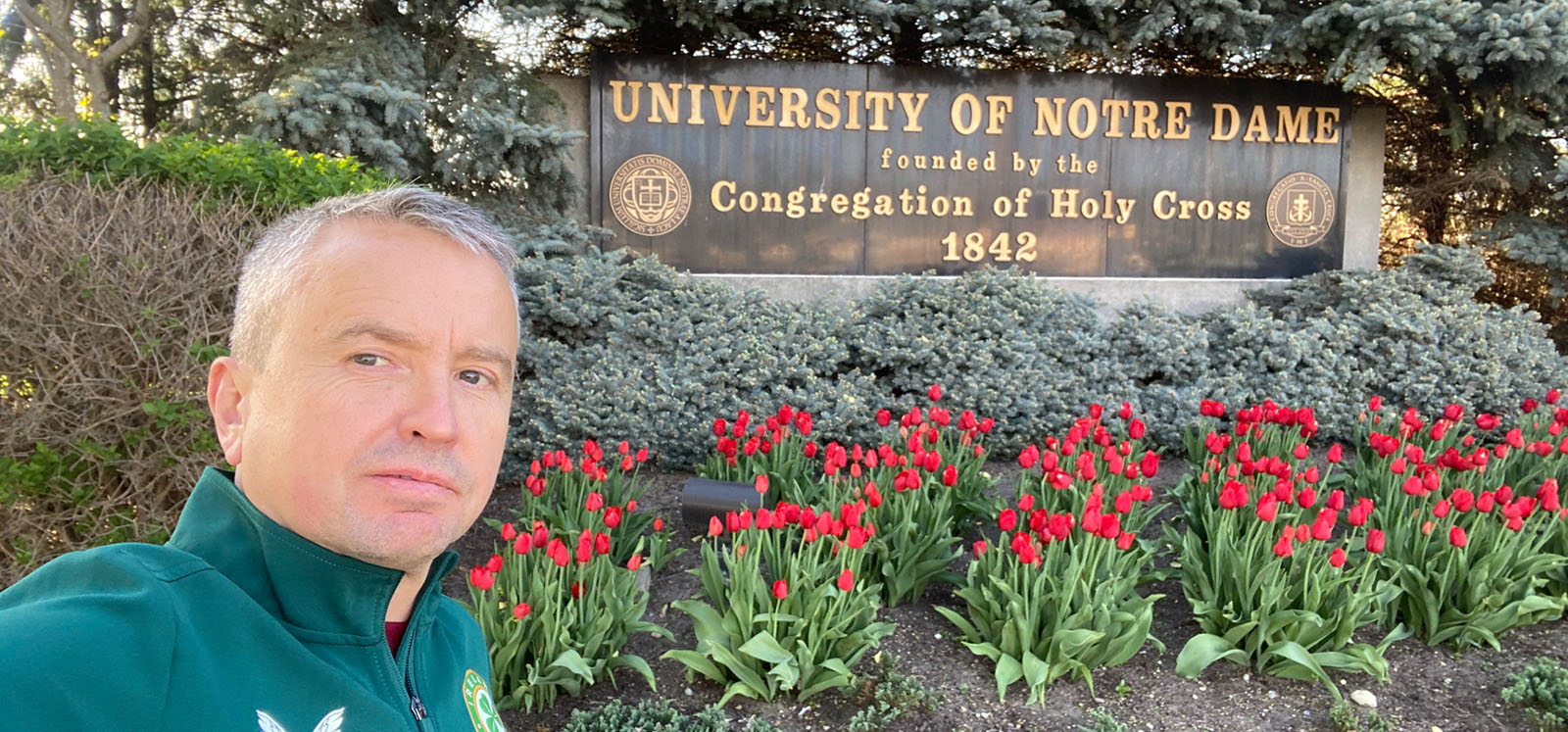

At the end of April 2025, I had the privilege of undertaking a two-week funded research Fellowship at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, USA. As a final year PhD candidate, my research examines the role of civil society in transitional justice in Northern Ireland and Colombia. The trip provided me with an opportunity to work closely with some of the leading global scholars and practitioners in the field of peacebuilding and transitional justice.

The main aim of the Fellowship was to engage with resources linked to The Legacy Project: Preserving and Engaging the Digital Archive of the Colombian Truth Commission. The Legacy Project, a collaborative initiative based at Notre Dame, preserves and manages a vast array of materials compiled by Colombia’s Truth Commission following the 2016 Peace Agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP. These materials—referred to as transmedia files—include testimonies, written volumes, videos, audio recordings, pedagogical tools, and artistic content. They are designed not only to preserve memory but also to engage local and global audiences with the narratives of Colombia’s victims and survivors.

The sheer scale and depth of the archive can feel overwhelming, especially for an early-career researcher trying to navigate it and identify relevant information. However, it is also an inspiring and powerful body of work, rich in memory, marked by narratives that reveal how Colombia’s Truth Commission centred victims and included civil society throughout its process.

My visit included the opportunity to meet with members of the Legacy Project team, who helped answer many of the questions that have emerged during my research and especially following recent fieldwork carried out in Colombia, where I interviewed lawyers, academics, judges, politicians, and victims' groups who had engaged with the truth-telling process. This provided an invaluable opportunity to connect practice and theory and to reflect on how Colombia’s model contrasts with Northern Ireland’s more ‘piecemeal’ approach to legacy.

During my visit, I also conducted three additional interviews for my research. One of the highlights was speaking with Professor Josefina Echavarría Álvarez, Director of the Peace Accords Matrix (PAM) programme at Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. The Kroc Institute was given the mandate to monitor the implementation of Colombia’s 2016 peace agreement, an unprecedented level of international academic involvement in a peace process. The Barometer Initiative—PAM’s real-time monitoring mechanism—uses a meticulous, evidence-based methodology to track over 500 stipulations in the agreement. I was fortunate to interview two other team members, one based in Notre Dame and the other in Bogotá, gaining insights on the interaction between civil society, state institutions, and data-driven implementation monitoring.

These conversations deepened my appreciation for the robust monitoring framework employed in Colombia, which not only fosters accountability but also facilitates the meaningful participation of civil society organisations in peace implementation. By contrast, the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland, while ground-breaking in many ways, lacked a formal monitoring mechanism—a widely acknowledged shortcoming.

Beyond interviews and archival research, the fellowship also allowed me to participate in various informal academic exchanges, including meetings, working lunches, and end-of-semester drinks receptions with staff and fellows from the Kroc Institute, the Kellogg Institute for International Studies, and the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies. These conversations helped me to better understand how transitional justice scholarship is situated within Notre Dame’s wider research ecosystem and global outreach and also provided opportunities to discuss future possibilities for academic exchange between Queen’s and Notre Dame.

Whenever I had the chance (and in between rain showers), I took the opportunity to experience and explore the campus itself—which is among the most iconic and picturesque in the United States. Spanning over 1,250 acres, its architectural landmarks include the Golden Dome, the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, and the famous Hesburgh Library with its towering ‘Touchdown Jesus’ mural, which, despite being busy with students cramming for exams, served as a peaceful study environment during my stay. The grounds also feature two lakes, a golf course, a performing arts centre, several museums, Harry Potter-style dining halls, and a scaled-down replica of the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes. The University’s world-famous ‘Fighting Irish’ sporting culture is also visible everywhere—from the 80,000-seat football stadium to the numerous state-of-the-art facilities for baseball, lacrosse, basketball, tennis, rugby, and even real football.

Although my visit took place during the final weeks of the semester, I was still able to catch a ‘Fighting Irish’ baseball game, on free hot-dog night, and listen to grown men in the bleachers make dubious noises and shout out random words which I wasn’t able to connect to anything that was happening on the field. I later discovered I had just missed a WNBA preseason basketball game held in another arena, just across the car park from the baseball stadium, a reminder of the importance of sport in university life at Notre Dame.

Looking back, I arrived at Notre Dame with a long list of questions and left with a deeper understanding of how transitional justice is practised, studied, and disseminated—both in Colombia and globally. The experience provided an ideal space to reflect on how ideas travel: how lessons from Colombia can inform policy and practice elsewhere, and how digital archives like the Legacy Project play a crucial role in sustaining victims’ voices long after the formal structures of truth commissions have wound down.

I would like to thank all those at Queen’s who made the trip possible, particularly Gladys, Wendy-Louise, and Louise for helping with travel logistics and making everything run smoothly. Despite recent global events, I even managed to get through US Customs without any drama! On the other side, I am especially grateful to my hosts at Notre Dame—Peter, Gráinne, Beth, Emma, and Josefina—for their warm welcome, generosity and support throughout my stay. Special thanks also to Paul for showing me some of the sights in the surrounding South Bend area—I look forward to catching up with him when he makes the reverse trip from Indiana to Belfast this summer.

Damien Rea

Supervised by Professor Kieran McEvoy, Damien’s working title for his research project is: “The role of civil society in transitional justice in Colombia: lessons to be learnt for Northern Ireland“.

He is looking at the impending implementation of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill (NITLRB), which intends to initiate legislation to deal with the legacy of the Northern Ireland conflict. Once enacted, it will see all conflict related prosecutions, police investigations, inquests and civil actions closed down as well as the introduction of a conditional amnesty scheme. The introduction of the Bill will lead to a significant mobilisation from civil society, with victims seeking legal advocacy and taking challenges.

Damien is working alongside the local NGO, the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ). The CAJ have been collaborating with QUB on legacy issues associated with Northern Ireland and are the partner organisation for the PhD project. On the Colombian side, he is examining the key role that civil society has played in their transitional justice process and identifying lessons learnt, with a particular focus on the victim-centric mechanisms that have been adopted.