Philadelphia, Here I Come! (1964)

By Dr Kelly Matthews

In June 1963, Brian Friel, his wife Anne, and their young daughters Paddy (Patricia) and Mary returned home to Derry from three months in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where Friel had been invited to observe Sir Tyrone Guthrie in rehearsals at his new repertory theatre. Friel had just published his short story collection The Saucer of Larks and won the Macauley Fellowship from the Arts Council of Ireland. Anne was expecting a new baby, and as she packed their daughters’ clothes for summer holidays in Donegal, Friel gathered onionskin pages of notes he had handwritten in Minneapolis and tucked them into a manila envelope so he could continue drafting his new play. The former maths teacher had listed his initial scene ideas using Greek letters—α, β, γ, δ—[Brian Friel Digital Archive MS 37,047.1.10] and on the outside of the envelope, he wrote himself a reminder: ‘1. There must be reactions of hearty (from the heart & belly) laughter. 2. There must be sadness—people must cry for grief.’ [BFDA MS 37,047.1.1] These gut-level extremes were modelled on Guthrie, whose ‘directing is aimed primarily at the heart and the belly, not the brain’, as Friel wrote of him in an American magazine.1

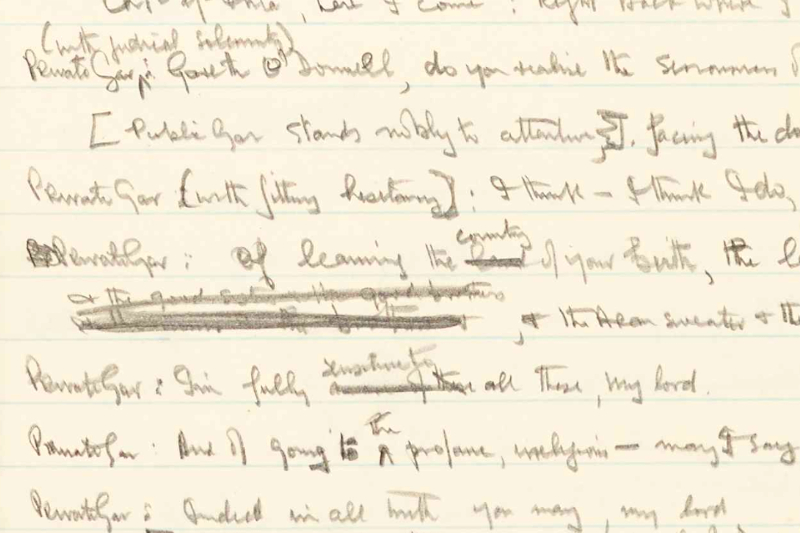

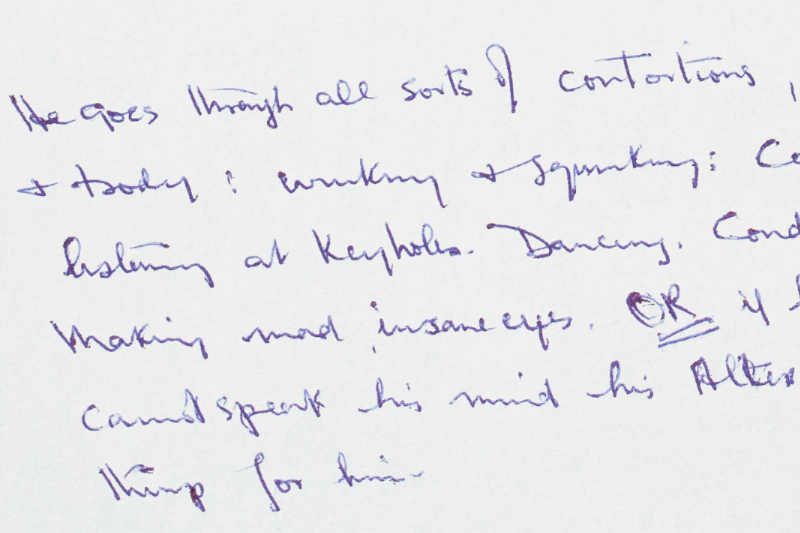

Friel layered the script of Philadelphia, Here I Come! with physical comedy, whose communicative power he had witnessed on Guthrie’s rehearsal stage as the director, a self-described ‘sucker for jokes and horseplay’,2 choreographed his production of Hamlet. In Friel’s earliest draft of Philadelphia, written in pencil in a feint-ruled notebook, main character Gar O’Donnell comes ‘bounding’ onstage, so ‘ecstatic with joy’ at the prospect of leaving for America that he rolls up his shop coat and ‘swings it round as if it were a machine gun’, then swiftly transforms into a footballer taking a free kick using the bundled coat as a ball [BFDA MS 37,047.2.1.5], then stands at military attention, saluting an imaginary judge who cross-examines him about ‘leaving the country of your birth, the land of the curlew + the snipe, + the Aran sweater + the Irish Sweepstakes’ [BFDA MS 37,047.2.1.6]. Friel noted that Gar ‘goes through all sorts of contortions, gyrations of face & body: winking & squinting: cocking snooks; listening at keyholes. Dancing. Conducting. Goose-stepping. Making mad insane eyes. OR if he is in company & cannot speak his mind his Alter Ego does these things for him.’ [BFDA MS 37,047.1.26] As Friel explained in a synopsis of the play, ‘I have heightened the comic element because the situation is essentially tragic.’3

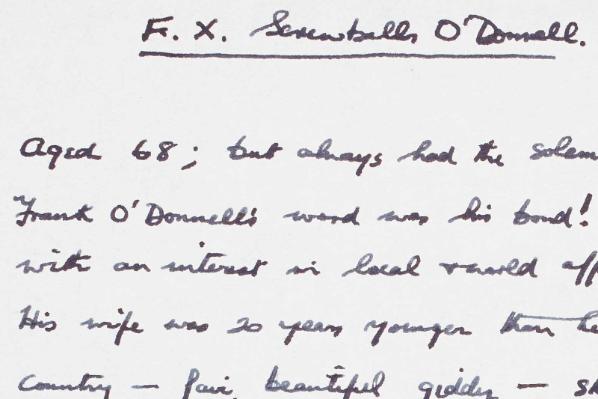

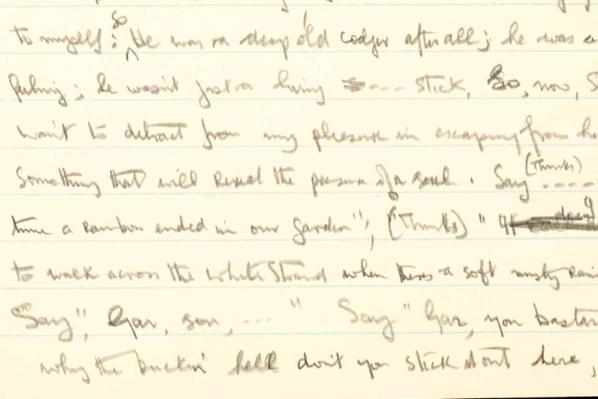

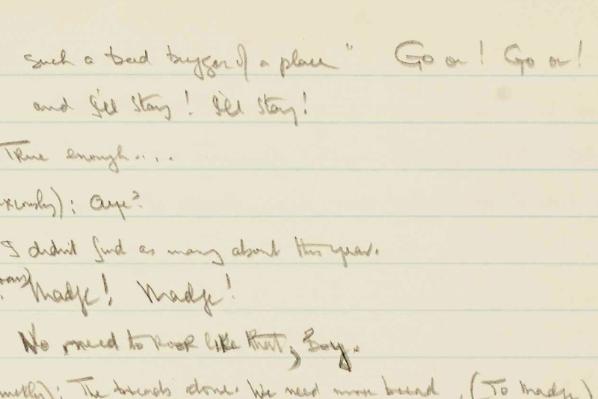

At the heart of the tragedy lies the gap between Gar and his widower father, Sean Bernard (S.B.) O’Donnell, a man of few words and fewer displays of emotion, secretly nicknamed ‘Screwballs’ by his son. In early drafts, S.B. was F.X. O’Donnell or Daniel E. O’Boyle [BFDA MS 37,047.1.16]. Friel asserted that ‘This is not another “American wake” story’ but ‘a story about growing-up, and the inarticulate love between a son and his father’ on a night that represents ‘the distillation of all his boyhood and growing-up and young manhood.’4 The two men tread well-worn paths through every conversation: Gar anticipates every word his father will speak and reflexively assumes ‘a surly, taciturn gruffness’, according to stage directions in the published play.5 And yet Gar wishes S.B. would ‘make one unpredictable remark’ or ‘Say, “Gar, you bugger you, why don’t you stick it out here with me for it’s not such a bad aul’ bugger of a place.”’ [BFDA MS 37,047.2.1.25] In a line deleted from the final script, Gar promises, ‘Say it, and I’ll stay! I’ll stay!’ [BFDA MS 37,047.2.1.26]

Gaps between father and son are mirrored by gaps between memory and truth. Gar treasures a memory of fishing with his father amid a rain shower that prompted them to share a coat, a hat, and a few bars of a song, sung by S.B. because ‘between us, at that moment there was this great happiness, this great joy—you must have felt it too […] although nothing was being said—just the two of us fishing on a lake on a showery day—and young as I was I felt, I knew, that this was precious […] and then, for no reason at all except that—except that you were happy too—you began to sing’ [BFDA MS 37,047.2.2.66]. But the song, and the moment, are nothing his father remembers when Gar finds the courage to ask him in their final conversation. [BFDA MS 37,047.1.12] Instead, S.B. has his own memory: Gar in a green gansey, holding tight to his father when the rain turned to lightning and thunder—and this, too, is S.B.’s memory alone.

Private Gar muses, ‘Your blue coat + his green gansey—did both of you imagine them?’ [BFDA MS 37,047.2.2.85] To the playwright, it didn’t matter. Friel changed the green gansey to a sailor suit in the published script, but he would continue to plumb the depths of discordant memories in his later plays.

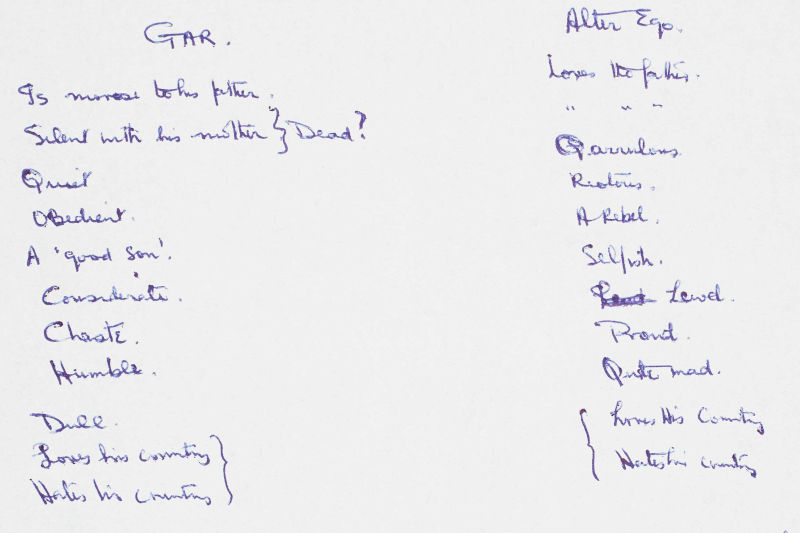

Before he settled on Philadelphia for Gar O’Donnell’s destination, Friel knew he wanted both halves of Gar’s inner and outer consciousness in full view on stage. To plot the contrasts between Gar O’Donnell and his ‘Alter Ego’, Friel drew two columns:

"He must primarily be himself, highly individual, but he is also THE IRISHMAN who appears to conform—and does—but who leaves." [BFDA MS 37,047.1.26]

Each of Gar’s two selves was to be played by a separate actor. In the script, they are labelled ‘Public Gar’ and ‘Private Gar’, or in shorthand, ‘Public’ and ‘Private’. Private is visible only to the audience, though he can be heard by Public. As Friel’s notes point out, Public Gar ‘never looks at him: you can’t look at your alter ego.’ [BFDA MS 37,047.2.1.29] The rest of the characters onstage are unaware of Private Gar’s existence.

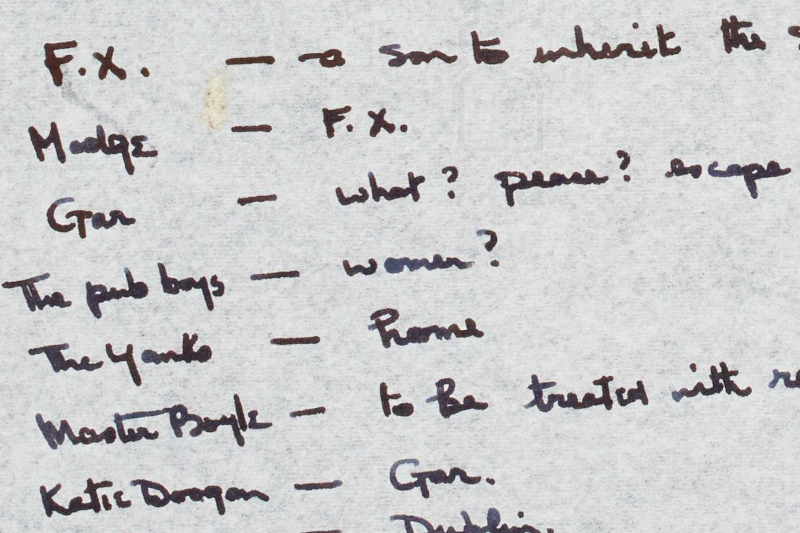

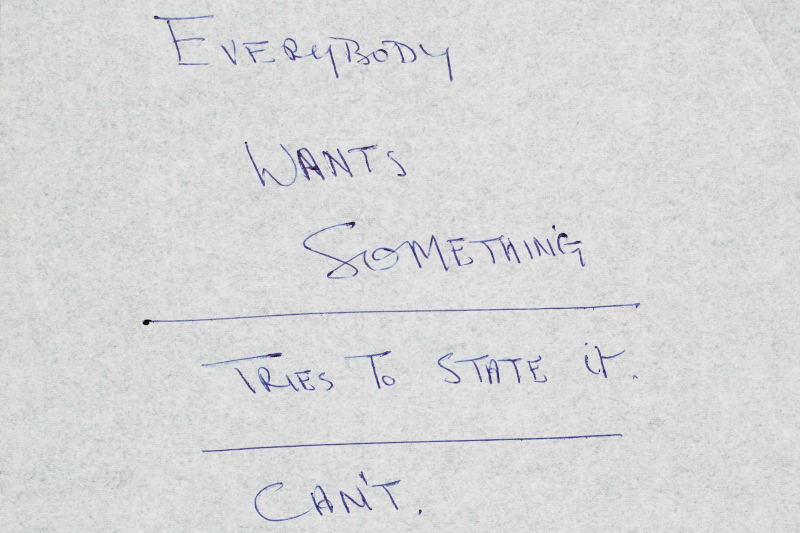

The play quickly took shape around each character’s repressed desires. Friel wrote it out for himself in block letters: [BFDA MS 37,047.1.20]

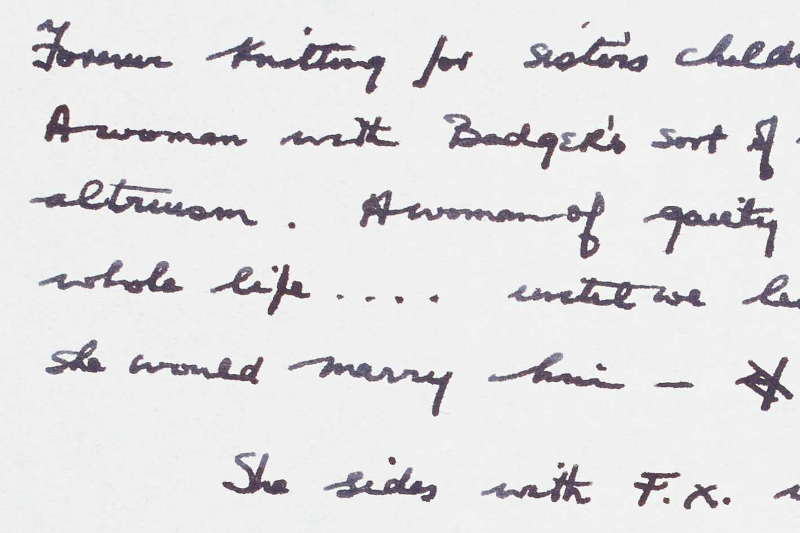

Gar’s father wants his son to inherit his shop; Madge wants to marry Gar’s father and has been waiting twenty years for his proposal [BFDA MS 37,047.1.18]; Gar’s friends want women; his American aunt Lizzy wants a sense of home; his old teacher wants to be treated with respect; his lost girlfriend still wants Gar; and Gar wants, Friel wondered, ‘what? peace? escape?’ [BFDA MS 37,047.1.20] Alone among all the characters, only Gar’s alter ego can voice his unspoken needs.

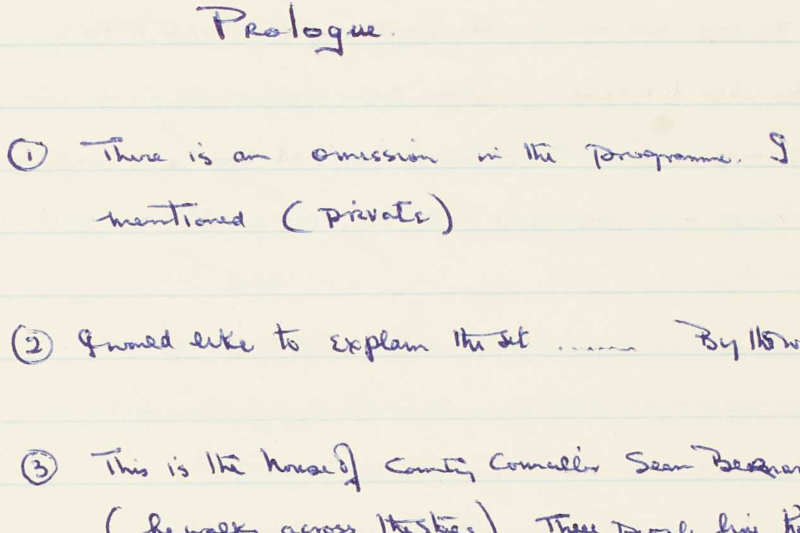

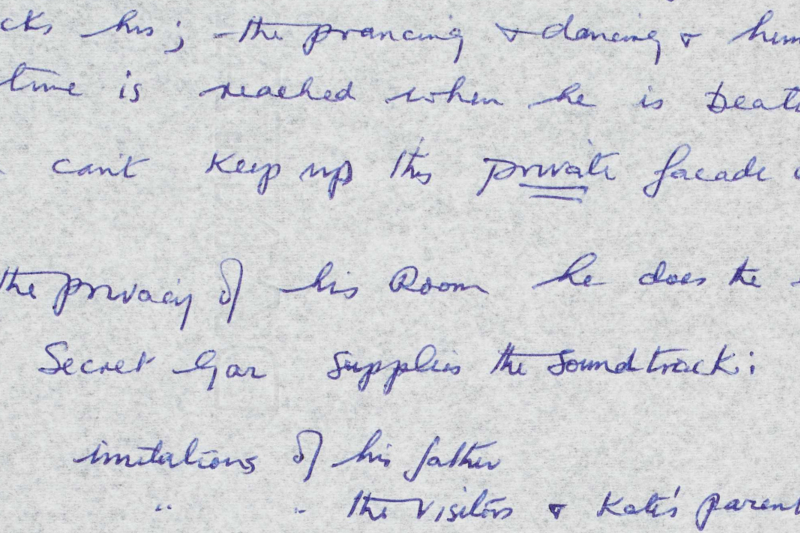

Friel knew from the start that the Private/Public division would be difficult to stage. In his first draft, he brainstormed three possible prologues in which Private Gar introduced the dichotomy, all of which were eventually discarded [BFDA MS 37,047.2.1.32]. Despite the challenges, Friel held fast to the dual-personality premise, convinced that on the night before Gar’s departure for America, ‘a time is reached when he is beaten to a stop—You can’t keep up this private facade endlessly.’ [BFDA MS 37,047.1.31] Initially, to mirror the prologue, Friel bookended the play with an epilogue, bringing all the characters onstage to look skyward as Public and Private Gar board the plane to America. In Friel’s notes, ‘his Alter Ego keeps up an endless stream of meaningless talk while Gar just sobs & sobs & sobs.’ [BFDA MS 37,047.1.22]

On 9 September 1963, Friel carried three copies of his finished script to the Marlborough Terrace post office near his house in Derry. He mailed two to his Curtis Brown agents in London and New York, and the third to Tyrone Guthrie in Minneapolis [BFDA MS 37,047.2.1.2 and MS 37,047.2.1.3]. And then, he and Anne waited. For their new baby, for the agents’ responses, and for Guthrie. The director returned to his family estate at Annaghmakerrig in late September and sent a typed critique of Philadelphia, suggesting numerous revisions, all of which Friel made. Guthrie loved Madge, whose characterisation was ‘so true to life, as lived in the Northern latitudes of our puritan isle; so just exactly like the women who have formed my own life, and therefore so endearing’, but Gar’s father, he thought, should show the audience ‘subtly and not a bit sentimentally, that he is missing the dead wife and is as lonely as Gareth.’6

‘Now for it’, Guthrie wrote, bracing himself—and Friel—before plunging into his most potentially damaging assessment: ‘I can’t decide whether the dodge of having two actors to play Private and Public, Ego and Alter Ego, is justified. I guess it ought to be tried.’ He called the epilogue ‘a mistake’ because ‘It adds nothing, and would look, I believe, a little pretentious in performance.’ Friel cut it. In terms of production, Guthrie warned, ‘I somehow think that neither English nor American managements will want to do it. Too “Irish” they’ll say; and I think maybe they’d be right.’7

The Friels’ daughter Judy—christened Judith, like Lady Guthrie—was born just a few days later, and in January 1964, word arrived from Curtis Brown’s London office that Oscar Lewenstein, a founding member of the English Stage Company, would pay £100 for a six-month option to produce Philadelphia, Here I Come! Lewenstein enlisted Hilton Edwards to direct Philadelphia at the 1964 Dublin Theatre Festival, hoping to attract the attention of English and American impresarios who could bring it to the West End or Broadway. When it eventually arrived in New York City after previews in Philadelphia, it struck such a chord with American audiences that it broke box office records as Broadway’s longest-running Irish play and grossed over a million dollars.8 It was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Play, and Friel was heralded as the voice of a new generation from Ireland.

[1] Friel, B. (1964), ‘The Giant of Monaghan’, Holiday 35 (5), 89-96, p. 92.

[2] Guthrie, T., A Life in the Theatre, New York: McGraw-Hill 1959, 69.

[3] Friel, B. (1964), ‘The Giant of Monaghan’, Holiday 35 (5), 89-96, p. 92.

[4] Guthrie, T., A Life in the Theatre, New York: McGraw-Hill 1959, 69.

[5] Guthrie, T., A Life in the Theatre, New York: McGraw-Hill 1959, 69.

[6] Friel, B. (1964), ‘The Giant of Monaghan’, Holiday 35 (5), 89-96, p. 92.

[7] Guthrie, T., A Life in the Theatre, New York: McGraw-Hill 1959, 69.

[8] Variety magazine weekly ticket sales reports, 2 March 1966 through 30 November 1966.

Kelly Matthews, Ph.D. is Professor of English at Framingham State University in Massachusetts and President of the American Conference for Irish Studies. Her first book, The Bell Magazine and the Representation of Irish Identity, was published by Four Courts Press in 2012, and she co-edited The Country of the Young: Interpretations of Youth and Childhood in Irish Culture, published by Four Courts in 2013. Her essays on Irish literature have appeared in Irish University Review, Éire-Ireland, New Hibernia Review, and other journals. She holds degrees from Harvard, Trinity College Dublin, Boston University, and Ulster University. Her current research focuses on the first decade of Brian Friel’s career.

-

Introducing the Friel Papers

To mark the launch of the Brian Friel Digital Archive in December 2022, the Friel Reimagined project commissioned a series of critical essays to illuminate the creation of Friel's most acclaimed plays and provide unique insights into the life and work of this most accomplished dramatist.

Author Play Dr Kelly Matthews, Framingham State University Philadelphia, Here I Come! Dr Lisa Fitzpatrick, Ulster University The Freedom of the City Mr David Grant, Queen's University Belfast Faith Healer Dr Alison Garden, Queen's University Belfast Translations Dr Bernadette Sweeney, University of Montana Dancing at Lughnasa