Faith Healer (1979)

By Mr David Grant

There is a jaw-dropping moment in Brian Friel’s Rehearsal Diary (Faith Healer 1979), his contemporaneous account of the play’s first rehearsal process, when in the entry for Saturday 24th February 1979, we read the words: ‘I don’t want to write any more.’1

He is responding to the demoralising experience of sitting through two poorly received previews of the original Broadway production, starring Hollywood legend James Mason in the title role. At first sight, this seems like a classic case of life imitating art, because Faith Healer is in essence a lightly disguised metaphor for the mercurial nature of artistic inspiration. But on further reflection, drawing on the materials now available in the Friel Papers, one realises that the play itself has been informed by a life-time of artistic doubts.

Faith Healer consists of four intricately interwoven monologues, in which the ‘fantastic’ Frank Hardy, his wife (or mistress?) Grace and manager Teddy give subtly divergent accounts of Frank’s fateful homecoming to Ballybeg. The play would go on to be a triumphant success at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre the following year but reading through the evidence of Friel’s painstaking writing process lends an added poignancy to his traumatic experience on Broadway.

Throughout his life, Friel famously eschewed any attempt by critics to make connections between an artist’s life and their work. This position reached its most public form when it became the central theme of Performances (2004), in which he allows the ghost of the Czech composer Janáček to vent his spleen against Anezka, a PhD student who is seeking to understand the composer’s Intimate Letters String Quartet in the context of his unrequited infatuation with a married woman. When Anezka tries to insist that ‘there must be a connection between the private life and the public work’, Janáček responds with evident exasperation: ‘You’d learn so much more by just listening to the music’ – a sentiment that surely reflects Friel’s own position.

So it feels almost disloyal to be prying into Friel’s private notes.

On the other hand, there is ample evidence in Friel’s own work that he gave considerable thought to the fate of his own literary estate. In Aristocrats (1979) he introduces us to Hoffnung, the prurient historian delving into the murky secrets of the denizens of Ballybeg Hall. Even more explicitly, in Give Me Your Answer Do! (1997), the agent of an American university who comes seeking to buy up a writer’s papers provides the major catalyst for the action. So, we must assume that when he entrusted his papers to the National Library of Ireland he was implicitly licensing our intellectual curiosity. In relation to Faith Healer, what emerges from the archive is a fascinating complement to Friel’s diary account of that first Broadway production – a multi-layered exposition of the lengthy gestation of what is widely regarded as his most accomplished play.

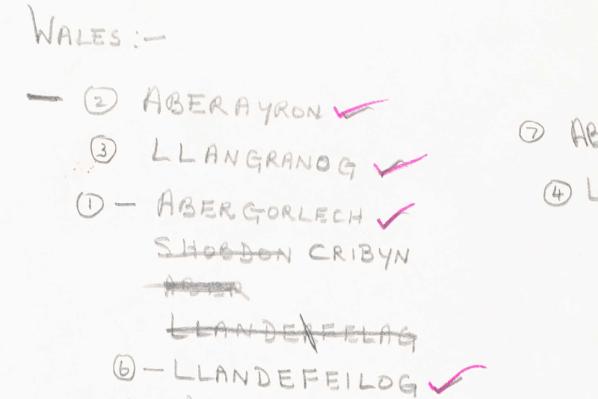

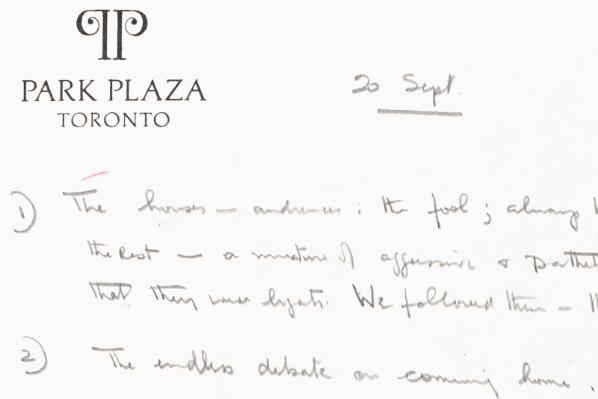

The archive is organised in such a way that we encounter its seemingly more ephemeral elements first, including a handwritten list of Scottish and Welsh placenames [BFDA MS 37,075.1.1.2] that together with a reference to George Steiner [BFDA MS 37,075.1.4.14], seems to foreshadow his later play, Translations, which drew so tellingly on Steiner’s After Babel. Even more delightfully, the second page [BFDA MS 37,075.1.1.3] is written on hotel notepaper (the Park Plaza in Toronto), suggesting either that Friel was staying there when he wrote the list, or that he made off with an ample supply given that the hotel logo also appears on a note from the following September! [BFDA MS 37,075.1.3.23] It is above all this human dimension that makes the archive so absorbing.

The collection moves steadily towards successively more substantive annotated drafts and no doubt, in time, detailed forensic analysis will reveal a coherent chronology of how the final script of Faith Healer was refined and developed. But even allowing for the difficulty in precisely dating some of the artefacts and materials, perhaps the most fascinating insights can be found in the possibilities considered and rejected by Friel as his thinking about the play began to take shape.

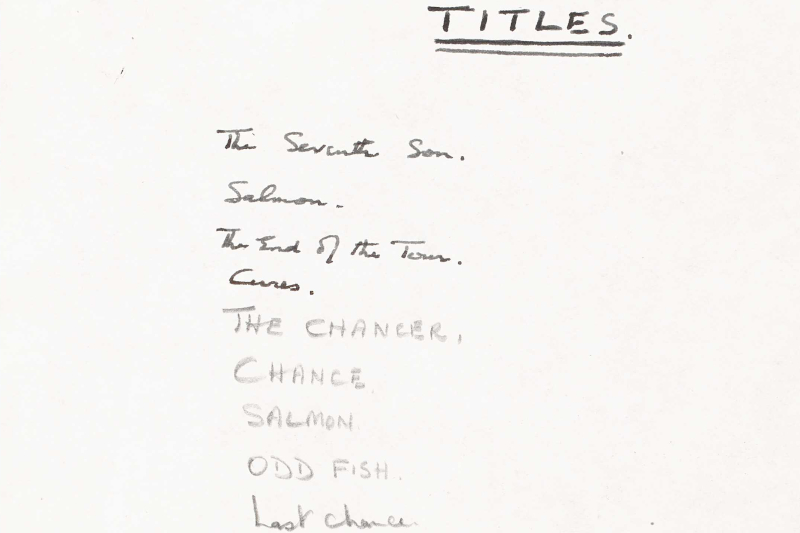

Take for example the page dated 21st May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.1.1] and boldly headed ‘TITLES’. The joy of being able to access a digital facsimile of this document lies in the extra layers of meaning that are revealed by the manuscript itself. The full list comprises three distinct hand-written elements, the first four titles being written in ink and in continuous script, the next four in pencilled capitals, and the final one in pencil but in the same style as the first four. This suggests that the initial block of titles dates from 21st May and that the others are later additions. We are therefore given an immediate insight into the trajectory of Friel’s thinking, even before we consider the actual titles themselves; and also a kind of road map with which to navigate other documents in the archive that help contextualise some of the options on the list.

Relatively few of the early pages in the collection are dated with the year, but those that are suggest that Friel’s creative process for Faith Healer began in the Spring of 1975. The earliest item appears to date from 15th April that year [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.45] and consists of notes under the heading The Seventh Son (the first title on the list discussed above), presumably a reference to the superstition that the seventh son of a seventh son was imbued with special powers.

‘Is a faith healer a poet, a saint, a charlatan?’, it begins. Then asks, ‘At what cost to himself? Is faith-healing an art? A craft? A technique? A con? … Is he accompanied – manipulated? Impaired? Smothered? – by a brother, a mother, a girlfriend?’ Just a few lines, but already (although the archive evidences a myriad of subsequent digressions) the germ of the play is there. The identity of Grace and Teddy as the key antagonists will be much slower to come into focus. And though this may be just subjective fancy, the handwriting looks, no, feels tentative and deeply personal, hinting perhaps at the close relationship between faith-healing and Friel’s uneasy sense of the precarity of his own craft as a dramatist.

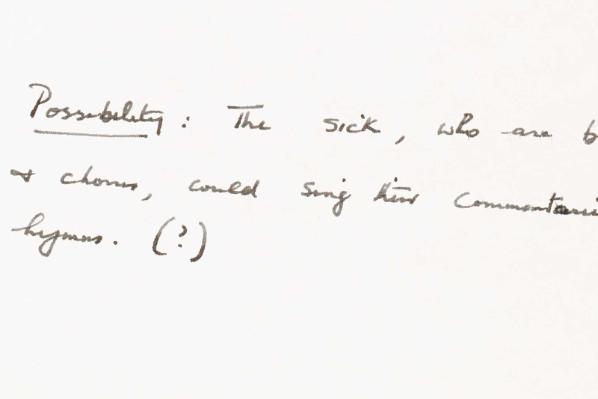

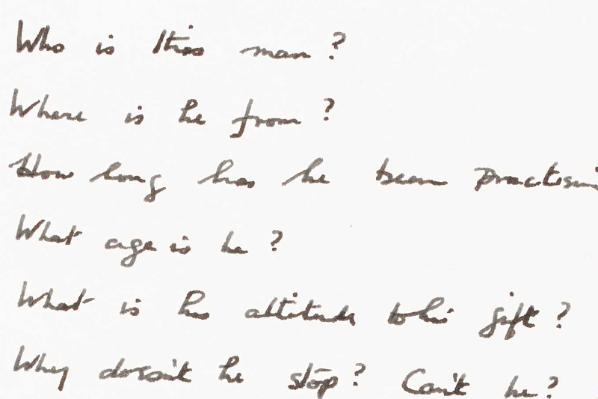

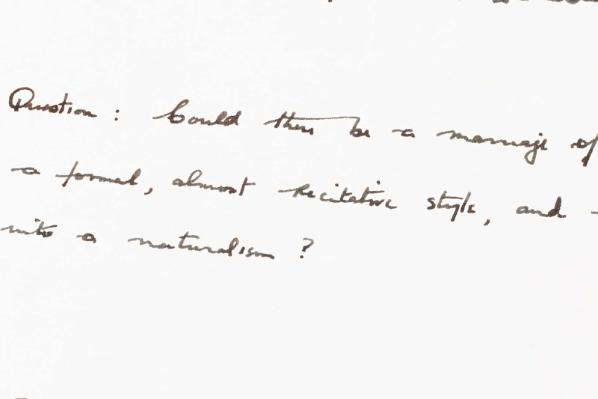

By 1st May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.44], the idea of the play being set mainly in a meeting hall has emerged, though with provision for other locations within the set (as in Philadelphia, Here I Come!). There is even the ‘possibility’ of a chorus of the sick who ‘could sing their commentaries to the air of hymns (?)’. And on the previous page [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.43], we see the first reference to the ‘group of local lads’ who will become Frank Hardy’s nemesis. By 5th May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.40], there is a list of character prompts beginning with ‘Who is this man?’, providing a telling insight into the meticulous craftsmanship of Friel’s writing process. And on the same date [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.39] a reflection on form.

Friel is on record more than once that a play arises from its form: the way, for instance, that Philadelphia, Here I Come! is driven by the unseen presence of Private Gar and Translations is shaped by presenting Irish as English. The Faith Healer archive opens up to scrutiny Friel’s struggle to identify an equivalently innovative stylistic device; having toyed with a wide range of casting schemes, he will eventually find it in that most traditional of theatrical forms – pure storytelling.

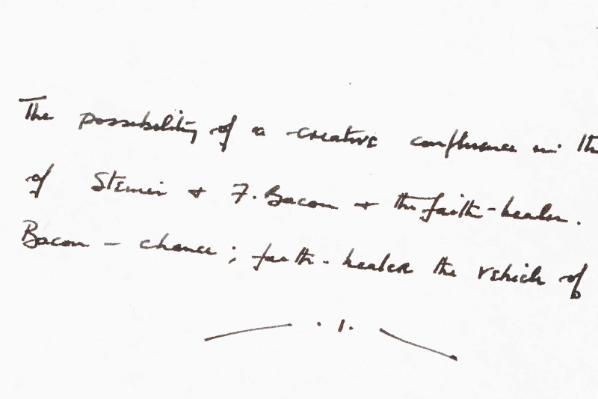

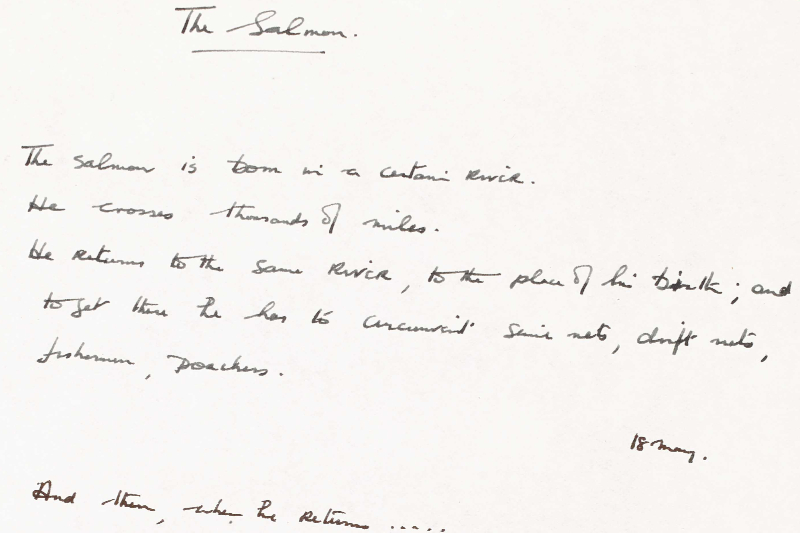

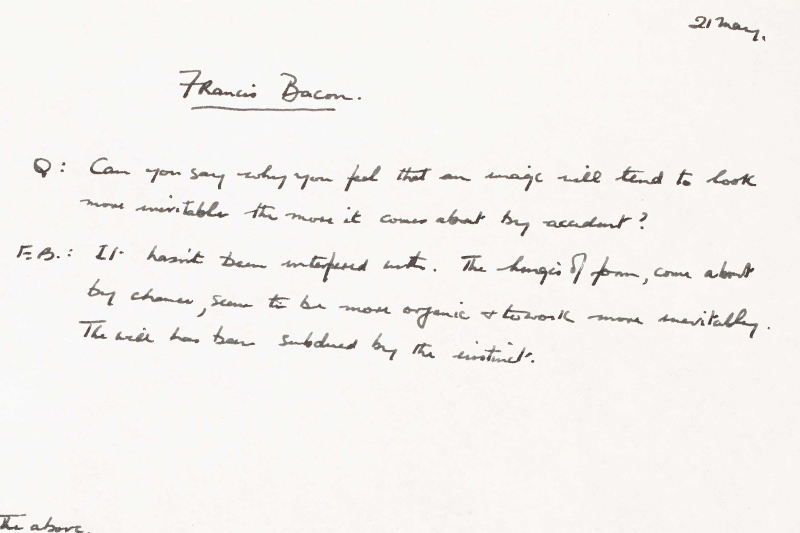

On 17th May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.47], there is a note about the second title on Friel’s list, The Salmon, the first hint of what will become a running theme in the playwright’s later work, the importance of returning home. And on the same day [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.34], another significant ‘possibility’ – ‘The power inducing arrogance and recklessness. And the destruction resulting from this’ – which foreshadows the ending of the play when Frank Hardy renounces chance. Friel attributes this concept on 21st May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.24] to his ‘chance’ reading of an interview with the painter Francis Bacon on the subject at this time. Two days earlier [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.30] Friel has speculated that Hardy could be the narrator of his own biography, a first hint at monologue form. By 23rd May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.16] he is considering two narrators, ‘Lily and Him’, and so the seed of a principal female antagonist is sown.

Tantalisingly, Friel considers possible casting options – Patrick Magee and Niall Tóibín [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.42] and the implications of each choice for the development of the character of Frank. On the 26th May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.12] he writes:

Thinking only in terms of the kind of Faith Healer that Magee would portray now seems to be diminishing the concept by making S.S. [presumably an abbreviation of Seventh Son] a POMPOUS, SELF-REGARDING man. Where is the scamp that the life-style suggests? The rogue?

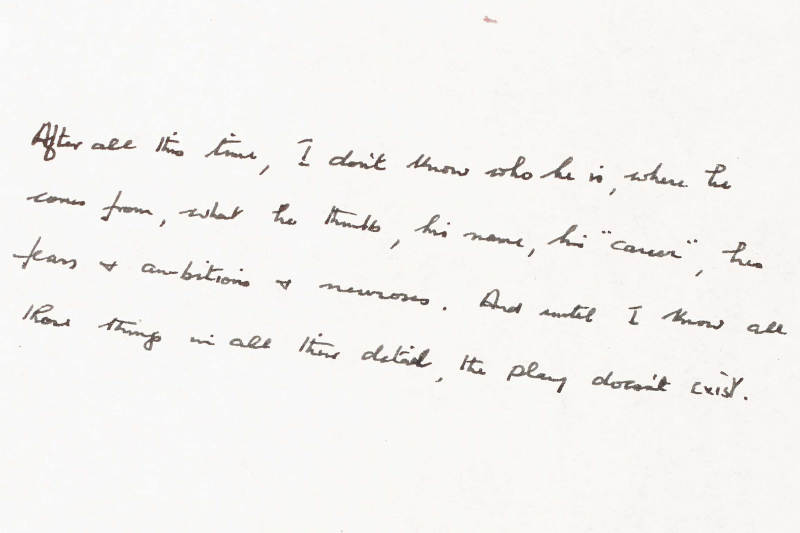

This note gives us a rare insight into the way the embodiment of a character in a writer’s imagination may influence how they write. But by 29th May [BFDA MS 37,075.1.2.6] Friel’s frustration at his lack of progress leaps off the page: ‘After all this time, I don’t know who he is, where he comes from, what he thinks, his name, his career, his fears and ambitions and neuroses. And until I know all those things in detail, the play doesn’t exist.’

The struggle to wrest a play from these ideas continues for another month, but on 23rd June there is a short revelatory note [BFDA MS 37,075.1.4.13] that suggests the eventual form of the play is beginning to emerge when he imagines what a character now called Frank says. As is clear from the subsequent notes and drafts that complete this section of the archive, Friel’s creative journey was just beginning, but the play’s essential architecture had become clear.

Friel, Brian. Plays 1 (London: Faber, 1996)

Friel, Brian. Performances (London: Faber, 2005)

Friel, Brian. Rehearsal Diary (Faith Healer, 1979) (Oldcastle: Gallery Press, 2022)

Grant David. The Stagecraft of Brian Friel (London: Greenwich Exchange, 2004)

Murray, Christopher (ed.). Brian Friel – Essays, Diaries, Interviews: 1964-1999 (Faber: London, 1999)

Pine, Richard. The Diviner (Dublin: University College Press, 1999)

[1] Brian Friel, Rehearsal Diary (Faith Healer, 1979) (Oldcastle: Gallery Press, 2022), p.38

David Grant is a Senior Lecturer in Drama at Queen’s University, Belfast, where he has been based since 2000. He is a former Programme Director of the Dublin Theatre Festival and Artistic Director of Belfast’s Lyric Theatre. He has enjoyed a long association as a theatre director with the work of Brian Friel, having directed Conleth Hill in Winners in 1984, Philadelphia, Here I Come! (Lyric Theatre, 1994 and U.S. tour, 1996) and two productions of Translations, of which one was in Hungarian for the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj in Transylvania (2001), and the other at the Brian Friel Theatre at Queen’s University (2012). He was privileged to have the opportunity to see Donal McCann in Faith Healer at the Abbey Theatre when he reprised the role in 1990 – a truly unforgettable experience.

-

Introducing the Friel Papers

To mark the launch of the Brian Friel Digital Archive in December 2022, the Friel Reimagined project commissioned a series of critical essays to illuminate the creation of Friel's most acclaimed plays and provide unique insights into the life and work of this most accomplished dramatist.

Author Play Dr Kelly Matthews, Framingham State University Philadelphia, Here I Come! Dr Lisa Fitzpatrick, Ulster University The Freedom of the City Mr David Grant, Queen's University Belfast Faith Healer Dr Alison Garden, Queen's University Belfast Translations Dr Bernadette Sweeney, University of Montana Dancing at Lughnasa