Translations (1980)

By Dr Alison Garden

When Brian Friel’s play Translations premiered in Derry’s Guildhall in 1980 helicopters hovered over the makeshift theatre and audience members were searched on the way in. The play was hotly anticipated. The audience, including politicians, writers and activists, gave the play a standing ovation. Today it is one of Friel’s most popular plays: regularly performed by theatre companies and taught in schools across Ireland and the UK.

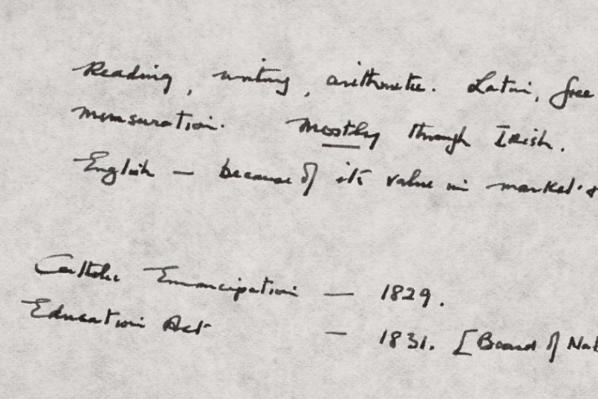

Set in 1833 in Baile Beag, a fictionalised town in County Donegal, all of Translations—with the exception of one crucial love scene—takes place inside a Hedge School. Hedge Schools were a vital source of education that had developed in the eighteen-century after the Penal Laws prohibited Catholic and Dissenting Schools. This Hedge School is run by Hugh and his son, Manus, where the pair teach Latin, Greek and arithmetic to their Irish-speaking students in exchange for money and food.

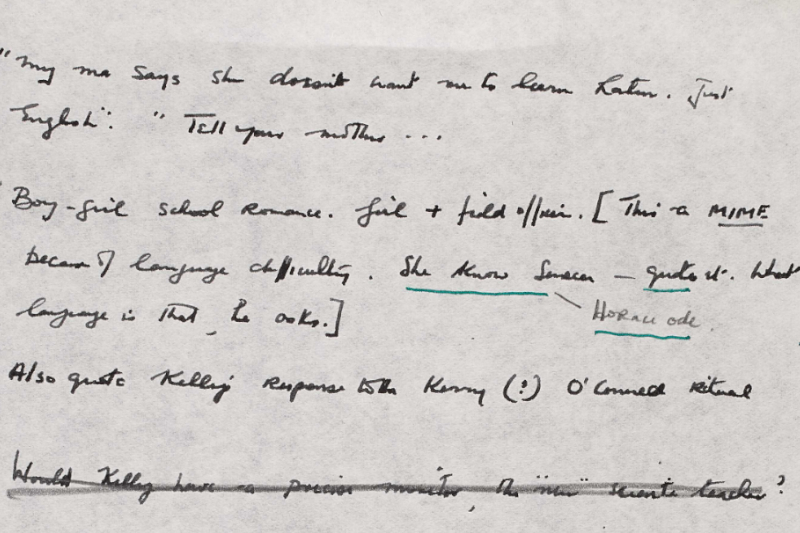

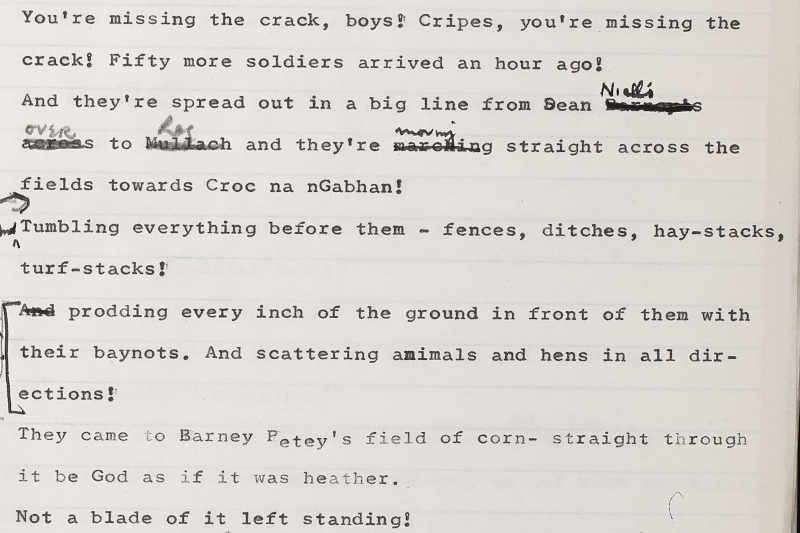

The drama really starts to unfold when Hugh’s younger son Owen turns up at the Hedge School accompanied by the British Royal Engineers, a group of soldiers who have arrived to map the local area as part of the first Ordnance Survey of Ireland. Part of this mapping process involved replacing ancient Irish language place names with English ones. Many of the characters are not happy with what they see as an act of colonial violence against their language and culture. Quote: BFDA MS 37,085.4.2.1

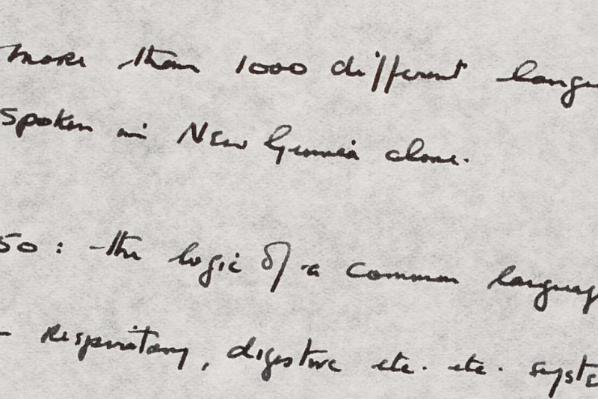

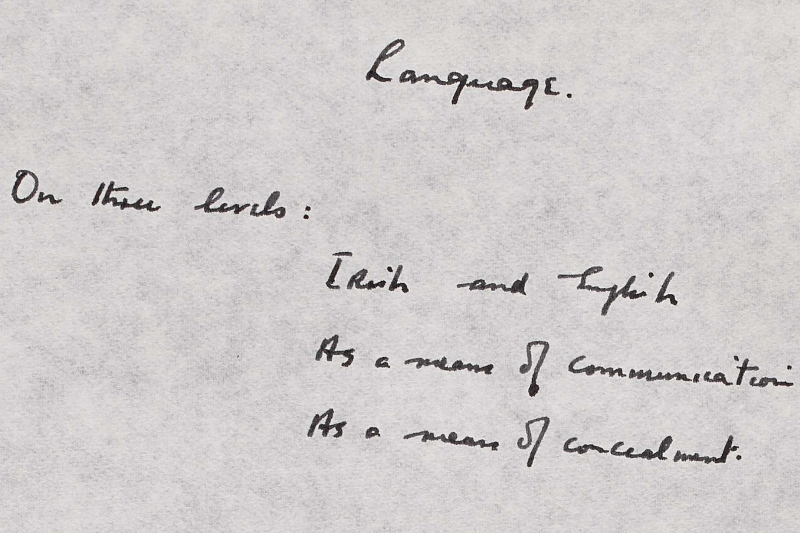

Translations is underpinned by a stunning theatrical device: the play is performed in the English language, despite the fact that nearly all of the characters are supposed to be speaking Irish. This generates some lively humour. More than this, though, it is a haunting reminder of what happened to the Irish language in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The play is ghosted by the sense that, as one of the soldiers says, ‘something is being eroded’.

Image: Brian Friel Digital Archive MS 37,085.1.1.14

TRANSLATIONS AND THE FIELD DAY THEATRE COMPANY

Translations itself is not just a literary masterpiece: it was also the first production from the Derry-based Field Day Theatre Company. Established by Friel and the actor Stephen Rea, who played Owen in the original production, Field Day aimed to produce art that responded to the ongoing conflict in the North. They sought to do this by creating an artistic and imaginative ‘fifth province’ that could transcend the divisions in Irish politics and society.

This first production of Translations toured across Ireland on both sides of the border. Other academics and writers would later join Field Day, including Seamus Heaney and Seamus Deane, and Field Day published a variety of pamphlets and anthologies. Their work was not always uncontroversial; they were criticised by some for their political stance and side-lining women in their early anthologies.

Although it was and is widely praised, Translations was also subject to a mixed reception, with a number of critics finding fault with Friel’s uses (and abuses) of history. For example, the men working on the Ordnance Survey are consistently called ‘English soldiers’ but, in actuality, the bulk of those who worked on the Ordnance Survey were civilians not military men. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that Translations was written and performed at the height of ‘The Troubles’ in the North, such liberties were a source of contention—both at the time and subsequently. The literary critic Edna Longley and historian Sean Connolly were amongst those early respondents who found Friel’s dramatic license questionable.

Image: Brian Friel Digital Archive MS 37,085.3.2.9

Returning to Friel’s archive gives us a fascinating insight into how Friel made use of Irish history in the writing of Translations in 1978 and 1979. An intriguing note left in Friel’s papers held at the National Library of Ireland (NLI) reveal that he felt there needed ‘to be a calculated misrepresentation of history’ if the play was going to achieve his intended impact (BFDA MS 37,085.1.6.006 19790531). In his diary entry for 22 May 1979, Friel recognises that his play is an ‘inaccurate history’ but the wealth of detail left to us in his NLI papers make it obvious that Friel researched Translations meticulously.

In these archival holdings we find references and copious notes to John Andrews’s study of the Ordnance Survey in Ireland, A Paper Landscape (BFDA MS 37,085.1.7; Patrick John Dowling’s history of The Hedge-Schools of Ireland (BFDA MS 37,085.1.10); and George Steiner’s exploration of language and translation, After Babel (BFDA MS 37,085.1.8).

There are numerous passing references to celebrated men from Irish history such as Daniel O'Connell, ‘The Liberator’—who played a key role in Catholic Emancipation in the early nineteenth century (BFDA MS 37,085.1.2.13)—and the Irish republican Robert Emmett who was killed in 1803 (BFDA MS 37,085.1.2.010).

There are some especially intriguing references to historical figures associated with the Ordnance Survey: including Colonel Colby, who wrote Memoir of the City and North Western Liberties of Londonderry and John O’Donovan, an Irish language scholar who worked on the Survey and would later become a Professor at Queen's University Belfast. References to these men and their work are dotted throughout the manuscripts found in various folders in the collections BFDA MS 37,085.1 through to MS 37,085.12. These figures lend their names to early versions of some of Translations’s characters as Friel crafted his play.

The 'BOY-GIRL SCHOOL ROMANCE'

For all of his diligent research, Friel wanted his play to be a work of art that had emotional resonance: in a comment to himself from 3 May 1979, Friel maintained that if the play was ‘a thesis about language or colonisation or famine, then scrap it’. Quote: MS 37,085.1.3.13

One of the most affecting and powerful episodes in Translations is the love scene between Maire and George Yolland that takes place in Act 2, Scene 2. The attraction between the two is illicit for two reasons: George is one of the English soldiers and Maire has previously been involved with Manus. It is important to remember that, for audiences watching this in Ireland in the 1980s, such romances would still have been highly dangerous and transgressive.

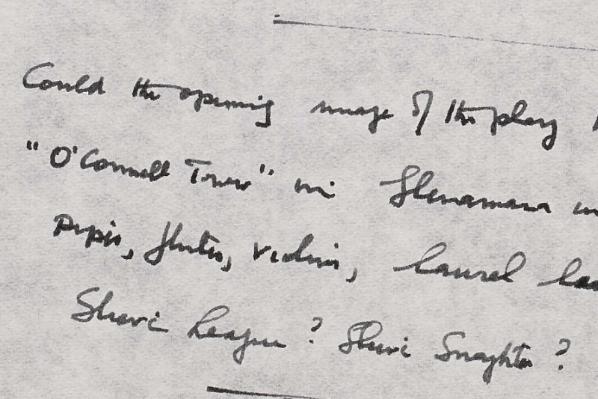

Regularly described as one of the best love scenes in modern theatre, this scene is the only one in the whole play that isn’t set in the schoolroom. This tells viewers how central it is to the drama. In fact, this romance, and this scene especially, were some of the very first images that came to Friel as he wrote Translations.

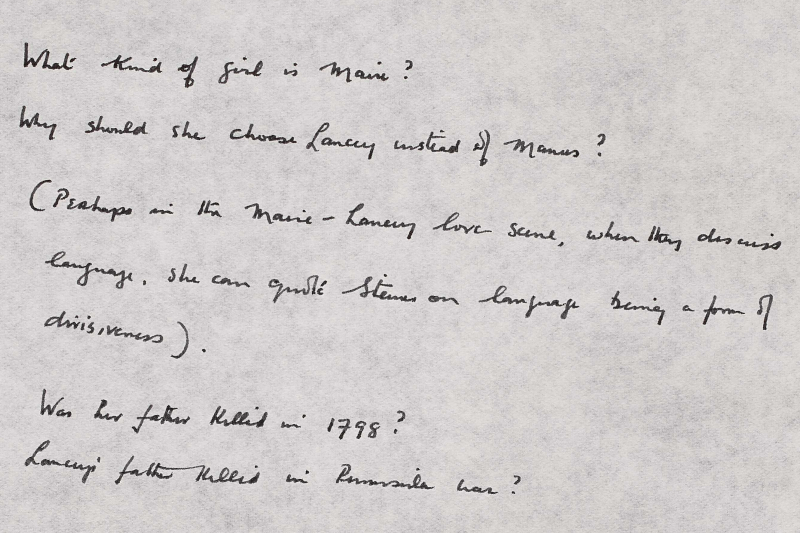

Papers from May 1978 (BFDA MS 37,085.1.1.10 & MS 37,085.1.1.11) give us an insight into Friel’s thinking as he plays with ideas. In a very early description of her character, on a page entitled ‘Maire’, written in pen, Friel adds in pencil what we can presume is a later annotation next to Maire’s name: Exogamy and Endogamy (BFDA MS 37,085.1.1.11). Those who know the play, or know the meaning of these words, will know their resonance. In the play’s final scene, one of the characters, Jimmy Jack, says to Maire:

Do you know the Greek word endogamein? It means to marry within the tribe. And the word exogamein means to marry outside the tribe. And you don’t cross those borders casually – both sides get very angry.

Image: Brian Field Digital Archive MS 37,085.1.1.10 [1978]

Part of the scene’s effectiveness comes from the lovers’ attempts to communicate despite speaking different languages: Maire speaks Irish and George, English. The scene famously culminates in an exchange of place-names but Friel’s papers reveal he danced around several ways of staging the couple’s growing feelings for one another. An early thought included, ‘a MIME because of language difficult’ (BFDA MS 37,085.1.2.7).

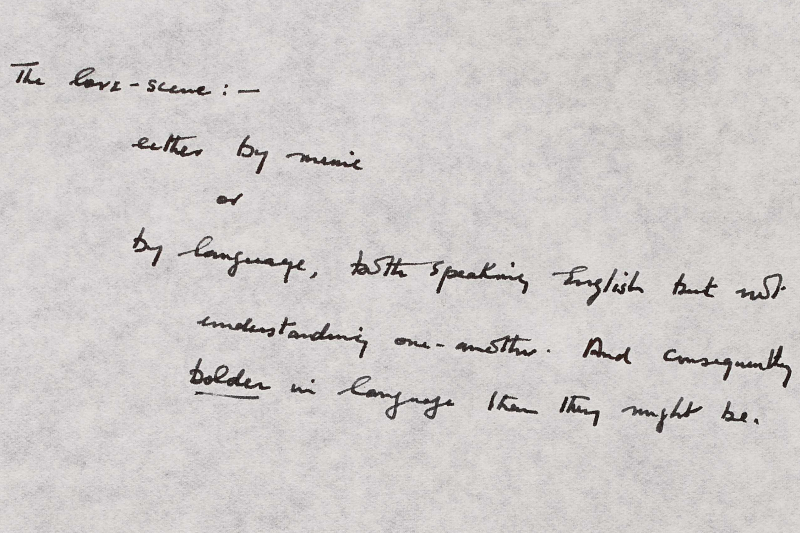

A later idea for the ‘love-scene’ was to stage their deepening love ‘either by music or by language, both speaking English but not understanding one-another. And consequently bolder in language than they might be’ (BFDA MS 37,085.1.3.4). Friel went with this second idea including the notion that they might be ‘bolder’ because they couldn’t speak the same language. Both Maire and George are more confident with their feelings in this scene than anywhere else in the play. They both say to the other ‘Say anything at all. I love the sound of your speech’. Maire is the most assertive, though, with her articulation of a very taboo desire: ‘I want you too, soldier’.

Despite the romantic optimism of this scene, things do not end well for these young lovers. In practical terms, Friel uses their plotline as a catalyst for what will follow in the rest of the play. In emotional terms, their burgeoning love acts as a vital thread in the affective tapestry of Translations. Friel’s papers tell us how important this scene was to his early envisioning of the play and how vital it was to him that the intensity of human life could be felt amongst his driving preoccupations of history and language. More than simply a ‘calculated misrepresentation of history’, Translations is a masterful exploration of what it means for people and cultures to speak to, and (mis)understand, one another.

Brian Friel, Brian Friel—Essays, Dairies, Interviews: 1964-1999 ed. Christopher Murray. London: Faber and Faber, 1999.

Brian Friel, Translations, London: Faber and Faber, 2000 [1981].

Marilynn J. Richtarik, Acting Between the Lines: The Field Day Theatre Company and Irish Cultural Politics 1980–1984. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994.

Dr Alison Garden is a UKRI Future Leaders Fellow at Queen’s University Belfast, where she leads a project on the cultural and social history of ‘mixed marriage’, or mixed relationships, in modern Ireland. She is the author of The Literary Afterlives of Roger Casement, 1899-2016 (Liverpool 2020) and is currently writing Love Across the Divide: desire and colonial culture in Northern Ireland, 1970-present. In addition to her academic work, Alison has written for TIME, Aeon, Al Jazeera, the Irish Times and radio content for BBC NI.

-

Introducing the Friel Papers

To mark the launch of the Brian Friel Digital Archive in December 2022, the Friel Reimagined project commissioned a series of critical essays to illuminate the creation of Friel's most acclaimed plays and provide unique insights into the life and work of this most accomplished dramatist.

Author Play Dr Kelly Matthews, Framingham State University Philadelphia, Here I Come! Dr Lisa Fitzpatrick, Ulster University The Freedom of the City Mr David Grant, Queen's University Belfast Faith Healer Dr Alison Garden, Queen's University Belfast Translations Dr Bernadette Sweeney, University of Montana Dancing at Lughnasa