Using the Stormont Brake

David Phinnemore and Lisa Claire Whitten

February 2024

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Introduction

When the Windsor Framework was announced in February 2023, the ‘Stormont Brake’ was heralded by the UK Government as redressing the ‘democratic deficit’ of the Protocol and providing a ‘firm guarantee of democratic oversight, and a sovereign veto for the United Kingdom on damaging new goods rules’. More recently, in its 2024 Safeguarding the Union Command Paper, the UK Government presented the Stormont Brake as providing ‘a powerful democratic safeguard that provides powers to stop the application of [EU] single market rules’.

Under the Stormont Brake, 30 Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLAs) from two different political parties, subject to certain conditions, can initiate a process for blocking the automatic application of certain EU acts amending or replacing an EU act that applies in Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Whether or not the Stormont Brake is actually activated, and the application of the relevant EU act suspended, will depend on whether the UK Government agrees that certain criteria have been met. As the UK Government has indicated, the Brake will not be available for ‘trivial reasons’.

The detailed arrangements for the operation of the Stormont Brake are set out in:

-

- Article 13(3a) of the Protocol/Windsor Framework (added 23 March 2023)

- Unilateral Declaration by the United Kingdom on Involvement of the institutions of the 1998 Agreement (made 23 March 2023)

- Windsor Framework (Democratic Scrutiny) Regulations 2024 (SI 2024/118) (in force 2 February 2024) and the accompanying Explanatory Memorandum

- Letter from Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to the Speaker of the Northern Ireland Assembly (2 February 2024)

Of the many questions that the existence of the Stormont Brake raises, we consider here the likelihood of there being EU acts to which it could be legitimately applied. To do this, we first consider the types of acts the EU adopts and which automatically apply under Article 13(3) and which could entail an amendment or replacement to an EU act applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Second, we consider the criteria that must be met for the Stormont Brake to be activated. These are set out in Article 13(3a). Third, we ‘test’ the criteria for applying the Stormont Brake. To do this we identify those EU acts adopted by the EU during 2023 that were automatically applied in Northern Ireland via Article 13(3). Based on the listing of acts provided on the EurLex website and supplemented by monitoring of the dynamic regulatory alignment taking place under the Protocol/Windsor Framework as part of the Post-Brexit Governance NI project, 685 such EU acts were adopted in 2023. We then consider the extent to which the Stormont Brake could have been legitimately applied to them. A further section considers some of the potential consequences of the Stormont Brake being applied.

The analysis explains the process for applying the Stormont Brake and provides an indication of the type and volume of EU acts that amend or replace relevant EU acts applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework and to which the Stormont Brake could be applied.

1. What types of EU Acts can the Stormont Brake cover?

EU Acts that automatically apply under the Protocol Windsor Framework as a consequence of the dynamic regulatory alignment provision in Article 13(3) generally fall into one of three categories.

First, there are EU acts adopted either jointly by the Council and the European Parliament (EP) or by just the Council. Such acts can update and/or introduce changes to existing EU acts, for example in response to policy developments.

Second, there are ‘delegated’ acts. These are EU acts that the European Commission or the Council has been empowered to adopt through an act of the Council or the Council and the EP. They are provided for in Article 290 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). Delegated acts may ‘supplement or amend certain non-essential elements’ (emphasis added) of the relevant act of the Council or the Council and EP, with the ‘objectives, content, scope and duration’ of the Commission’s power being ‘explicitly defined’. Supplements or amendments to ‘essential elements’ may not be the subject of a delegation of power.

A third category of EU act comprises ‘implementing’ acts. These can either be ‘Decisions’, ‘Directives’ or ‘Regulations’. They are generally adopted by the European Commission, but occasionally the Council, and they put into practice – i.e. implement – via legislation what has been previously agreed in acts adopted by either the Council or the Council and the EP. Most implementing acts concern very technical, and often specific issues. Some relate to specific geographical locations.

2. The Stormont Brake Criteria

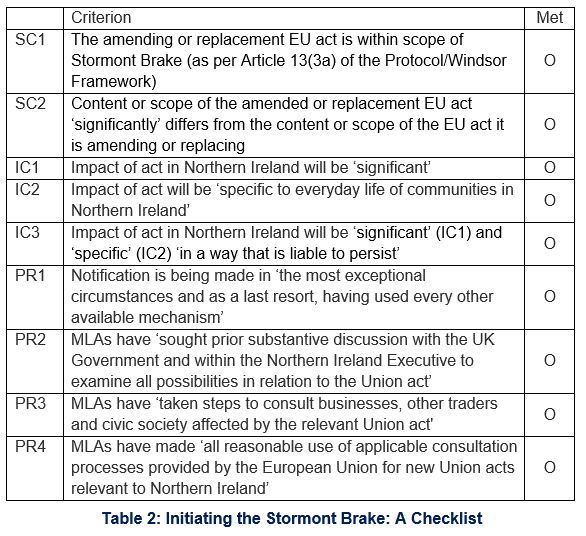

For the Stormont Brake to be activated and the application of an EU act in Northern Ireland suspended, the act must meet five criteria: two concerning scope and three concerning impact. In initiating the process, MLAs also need to fulfil a series of procedural requirements. The decision on whether to activate the Stormont Brake is then for the UK Government to take based on whether the criteria have been met.

2.1 Scope Criterion 1 (SC1): is the EU act that is being amended or replaced within the scope of Article 13(3a)?

The Stormont Brake can only be used with regard to an EU act that amends or replaces an EU act applicable under Protocol/Windsor Framework. As Article 13(3) notes ‘where this Protocol makes reference to a Union act, that reference shall be read as referring to that Union act as amended or replaced’. The EU act therefore needs to be one referenced in the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Few EU acts are specifically referenced in the actual text of the Protocol/Windsor Framework; most are referenced in its Annexes. Importantly, these ‘form an integral part of th[e] Protocol’ (Article 19).

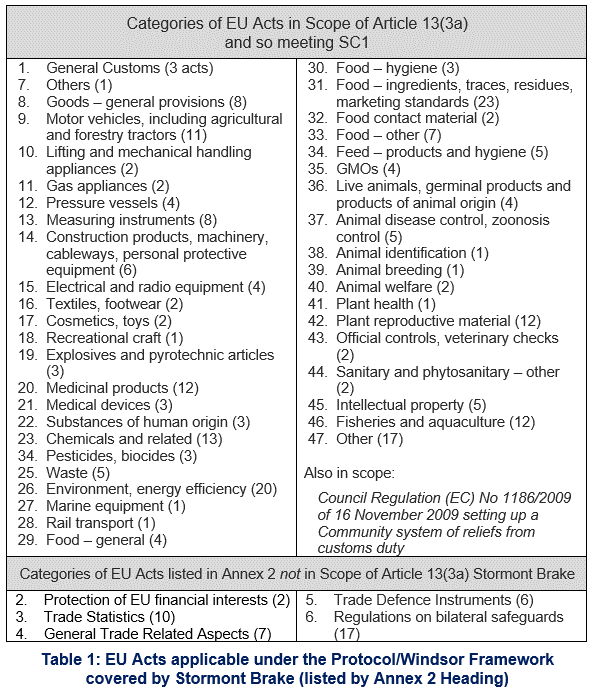

However, not all EU acts referred to in the Protocol/Windsor Framework fall within the scope of Article 13(3a). It is only those that amend or replace EU acts listed in Annex 2, i.e. those relating to the movement of goods. The Stormont Brake cannot be used with regard to amendments and replacements to EU acts concerning individual rights under Article 2 (Annex 1), VAT and Excise (Annex 8), the Single Electricity Market (Annex 9) or state aid and subsidies for agriculture (Annex 10).

Moreover, even within Annex 2, the Stormont Brake cannot be applied to all listed EU acts. Explicitly outside its scope are 42 EU acts listed under headings 2-6, e.g. trade defence measures and EU trade agreements with non-member states (see Table 1).

The Stormont Brake therefore primarily covers amendments and replacements to EU acts concerning areas of devolved competence (i.e. acts in areas where the Northern Ireland Assembly has legislative competence). However, the UK Government has indicated that some acts within the scope of the Stormont Brake do extend beyond devolved issues.

2.2 Scope Criterion 2 (SC2): does the content or scope of the amended or replacement EU act significantly differ from the content or scope of the EU act it is amending or replacing?

Second, for the Stormont Brake to be applied, the content or scope of the EU act as amended or replaced needs to ‘significantly’ differ ‘in whole or in part’ to the act as it was before being amended or replaced. Key here is not only whether there is a difference between the existing EU act and the act as amended/replaced, but that any difference is ‘significant’.

2.3 Impact Criteria (IC1, IC2 and IC3): does the amended or replacement EU act as a consequence of the amendment or replacement have ‘a significant impact specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland in a way that is liable to persist’ (Article 13(3a)?

Third, the impact in Northern Ireland of the EU act as amended or replaced needs to be:

-

- ‘significant’ (IC1)

- ‘specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland’ (IC2), and

- ‘in a way that is liable to persist’ (IC3).

The Protocol/Windsor Framework is silent on how these criteria are to be interpreted and no guidance has been issued by either the EU or the UK Government.

2.4 Procedural Requirements (PR1, PR2, PR3 PR4): has the Stormont Brake been initiated in accordance with procedural requirements?

Fourth, MLAs can only initiate the Stormont Brake process where several procedural criteria have been met. A notification of the Stormont Brake’s initiation can only be made:

-

- ‘in the most exceptional circumstances and as a last resort, having used every other available mechanism’ (PR1);

- where MLAs have ‘sought prior substantive discussion with the UK Government and within the Northern Ireland Executive to examine all possibilities in relation to the Union act’ (PR2);

- where MLAs have ‘taken steps to consult businesses, other traders and civic society affected by the relevant Union act’ (PR3); and

- where MLAs have made ‘all reasonable use of applicable consultation processes provided by the European Union for new Union acts relevant to Northern Ireland’ (PR4).

While most requirements involve practical steps that can be demonstrably fulfilled, requirements are not specifically defined and are therefore open to interpretation, e.g. ‘most exceptional circumstances and as a last resort’ (PR1) and ‘all reasonable use’ (PR4).

To meet the procedural requirements, MLAs will be able to draw on the work of the Assembly’s newly formed Windsor Framework Democratic Scrutiny Committee, whose purpose is ‘to assist with the observation and implementation of Article 13(3a)’. Its work includes:

-

- the examination and consideration of replacement EU acts,

- the conduct of inquiries and publication of reports in relation to replacement EU acts,

- engagement with businesses, civil society and others as appropriate in relation to replacement EU acts,

- engagement with the UK Government in relation to replacement EU acts,

- engagement with Ministers and Northern Ireland departments in relation to replacement EU acts.

To support the work of Windsor Framework Democratic Scrutiny Committee, the UK Government has committed to the timely provision of relevant information on proposed or adopted EU acts to which the Stormont Brake could potentially be applied. It has also committed to provide the Assembly with the same information on such acts as it provides Parliament in Westminster (e.g. Explanatory Memoranda).

2.5 MLAs supporting and the UK Government Applying the Stormont Brake?

MLAs may seek the application of the Stormont Brake if they believe the two scope and three impact criteria have been met and that they have fulfilled the four procedural requirements (see Table 2).

Where 30 MLAs from at least two different parties (but excluding the Speaker and Deputy Speaker) – or 30 MLAs including one from a political party and one independent MLA – believe the criteria have been met and are in favour of the Stormont Brake being applied they may notify the Speaker of the Assembly. They must do so within ten working days of the end of the two-month ‘scrutiny period’ following the publication in the Official Journal of the European Union of the EU act in question.

The notification must provide ‘detailed reasons’ for seeking to prevent the application of the relevant act and, in ‘a detailed and publicly available written explanation’, evidence that the scope and impact criteria have been met and the procedural requirements have been followed. It is expected that the notification will specify an MLA as the ‘lead member’.

If the Speaker is content that 30 MLAs support the notification, they forward notification to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. No vote in the Assembly is required. The notification must be forwarded to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland within nine working days of the end of the two-month ‘scrutiny period’.

The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland must then decide if they believe that the two scope (SC1, SC2) and three impact criteria (IC1, IC2, IC3) have been met and the four procedural requirements (PR1, PR2, PR3 and PR4) have been followed. Before doing so they may request further information, for example from the MLA named as 'lead member’ for the notification.

If the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland decides that the criteria have been met and the procedural requirements followed, the UK Government notifies the European Commission, and the application of the relevant EU act is suspended. In its notification, the UK Government must provide a ‘detailed’ explanation of how the criteria have been met. The UK Government is committed to ensuring that any notification is made ‘in good faith’. Where the European Commission considers the explanation insufficient, it may request within two weeks further explanation from the UK Government. The UK Government is obliged to respond within two weeks. The UK Government may request further information from the 'lead contact’ MLA.

Where the UK Government decides that one or more criteria have not been met or the procedural requirements not followed, it must provide written reasons to the Northern Ireland Assembly and is committed to doing so ‘without undue delay’. The UK Government has noted that such a decision not to apply the Stormont Brake does not prevent a separate notification being made in relation to the same EU act.

Of note is that if the UK Government does apply the Stormont Brake, its application only concerns the specific amending or replacement EU act. The original EU act continues to apply in its unamended/replaced form. Moreover, where the scope and impact criteria are only met in respect of part of the amending or replacement act, non-application only applies to the relevant part of the act. The rest of the amending or replacement act applies.

3. Testing the Criteria for applying the Stormont Brake – The Scope Criteria

How often the Stormont Brake might be applied will depend on: (a) the number of amending or replacing EU acts applicable to which it can be applied, and (b) whether the scope and impact criteria for its use are met.

As noted (see 1 above), there are essentially three types of EU acts that can update and/or introduce changes to EU acts applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework via the dynamic regulatory alignment process in Article 13(3):

-

- Acts adopted either jointly by the Council and the EP or by the Council

- Delegated acts

- Implementing acts

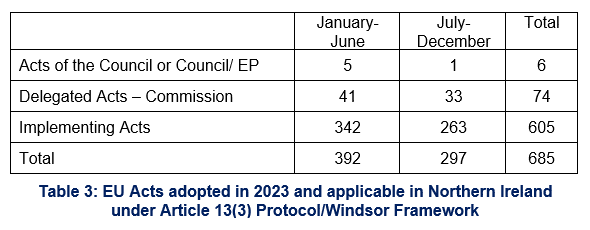

The number of each type of act adopted annually will vary. Based on the listing of acts provided on the EurLex website and supplemented by monitoring as part of the Post-Brexit Governance NI project, we identified 685 acts in 2023 that were adopted by the EU and which became applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework due to Article 13(3). Importantly, not all of these were ‘amending’ or ‘replacement’ acts. Moreover, not all fell within the scope of Article 13(3a) and so potentially the Stormont Brake.

3.1 How Many Amending and Replacement Acts?

In the case of acts adopted either jointly by the Council and the EP or by the Council, the number potentially subject to the Stormont Brake was small. In the first six months of 2023, for example, the EU adopted five such acts replacing or amending existing EU acts applicable in Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. In the second half of 2023, only one such act was adopted (see Table 3).

The number of ‘delegated’ acts adopted annually can be expected to be higher. In 2023, 74 such acts concerning EU acts applicable in Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework were adopted. Of the 41 adopted in the first six months of 2023, 35 introduced amendments or replacements to the applicable EU act. The remainder either corrected specific language versions of EU acts, ‘supplemented’ or updated existing acts, or were of limited duration and have since expired. In the second six months of 2023, the EU adopted 33 delegated acts relating to EU acts applicable in Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Of these, 23 introduced amendments or replacements to the applicable EU act; the remainder generally concerned (primarily language) corrections or supplements to EU acts. Of the 74 delegated acts adopted in 2023 and automatically applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework via Article 13(3), around three-quarters (78%) actually formally ‘amended’ or ‘replaced’ EU acts applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework.

The largest number of acts adopted by the EU in 2023 and made applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework through the process of dynamic regulatory alignment in Article 13(3) are ‘implementing’ acts. We identified 605 such acts, 342 of which were adopted in the first six months of 2023 with a further 263 being adopted in the second half of the year. These 605 implementing acts comprise 88% of the EU acts adopted in 2023 that automatically apply under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. As noted (see 1 above), implementing acts do not ‘amend’ or ‘replace’ EU acts, they implement them. As such, they cannot, by definition, be considered to be within the scope of Article 13(3a) and the Stormont Brake.

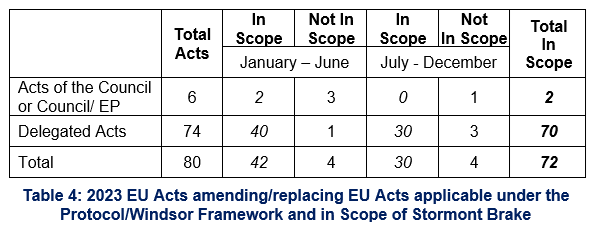

With the exclusion of implementing acts, we are left with 80 EU acts adopted by the EU in 2023 and made applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework through Article 13(3). These EU acts could potentially be subject to the Stormont Brake provided the scope criteria are met. Of these, 22 Delegated acts do not strictly ‘amend’ or ‘replace’, but generally ‘supplement’ or ‘correct’ EU acts applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. As such, they could be deemed to be beyond the scope of the Stormont Brake. For the purposes of this exercise, however, they are not being ruled out of scope at this stage.

3.2 Scope Criterion 1 (SC1): is the EU act that is being amended or replaced within the scope of Article 13(3a) Protocol/Windsor Framework (i.e. listed in headings 1 or 7-47 of Annex 2)?

When SC1 is applied to the six EU acts adopted by the Council or by the Council and the EP and the 74 delegated EU acts adopted by the Commission in 2023 made applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework via Article 13(3), eight concern EU acts – primarily concerning state aid – that are outside the scope of Article 13(3a), i.e. EU acts not listed in headings 1 or 7-47 of Annex 2.1

This leaves two acts adopted jointly by the Council and European Parliament meeting SC1 for the use of the Stormont Brake and 70 delegated acts adopted by the Commission (see Table 4).

The two ‘in-scope’ acts are ones adopted by the Council and the EP:

-

- Regulation (EU) 2023/607 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2023 amending Regulations (EU) 2017/745 and (EU) 2017/746 as regards the transitional provisions for certain medical devices and in vitro diagnostic medical devices

- Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on the making available on the Union market and the export from the Union of certain commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation and repealing Regulation (EU) No 995/2010

The 70 delegated acts concern primarily product standards.

These 72 ‘in scope’ acts are now considered in respect of the remaining criteria.

3.3 Scope Criterion 2 (SC2): does the content or scope of the amended or replacement EU act significantly differ from the content or scope of the EU it is amending or replacing?

Turning to the second scope criterion (SC2) – on whether the amended or replacement EU act significantly differ from the content or scope of the EU act it is amending or replacing – the first of the two acts adopted by the Council and the EP, Regulation (EU) 2023/607 on certain medical devices, would not appear to fall within scope. This is because it was limited to introducing extensions to existing transition periods for those implementing new standards for medical devices and in vitro medical devices as laid down in the two earlier EU acts (Regulation (EU) 2017/745 and Regulation (EU) 2017/746). The extensions gave more time for manufacturers to ensure relevant devices are compliant with new standards and can be certified to indicate as much as a matter of EU law. This being so, it is doubtful that this Regulation would have met the ‘significant’ change to ‘content’ or ‘scope. Of note here too is the welcome that the UK Government gave to the Regulations. The UK subsequently extended related transition periods for the acceptance onto the GB market of ‘CE’ marked medical devices.

As regards Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 on deforestation, the UK Government’s initial position was that the European Commission’s proposed regulation differed ‘fundamentally’ from Regulation (EU) 995/2010 which it replaced, although did not specify how. The UK Government subsequently committed to produce an analysis of the regulation’s ‘potential applicability’ under Article 13(3) which would presumably address the scope question. That assessment has not yet been produced.

As for the 70 delegated EU acts adopted during 2023, these by definition should not have affected – ‘significantly’ or otherwise – the ‘scope’ or the ‘content’ of the EU act that they amend or supplement. This is because, as noted (see 1 above), delegated acts are limited to amending and supplementing ‘non-essential elements’. The amendments and replacements that they introduce are therefore unlikely to have met SC2.

A delegated EU act having a ‘significant’ change to the ‘scope’ or ‘content’ of the original EU act cannot be ruled out, however. The European Commission in proposing legislation does on occasion exceed its competences and so legislation has been annulled. However, the Commission’s record regarding delegated acts suggests that it generally acts within the scope and content of the original EU act. A 2019 study for the EP noted that MEPs only objected to ten of the 848 (i.e. 1.2%) delegated EU acts that the Commission introduced between 2010 and May 2019. And in only one instance did the EP cite the Commission exceeding its mandate as the reason for objection. Notably, the Council only objected to three delegated acts during the same period.

Overall, the likelihood of a many EU amended or replacement acts meeting the ‘content and scope’ criterion (SC2) for MLAs to initiate the Stormont Brake, based at least on the data from 2023, appears to be low. In principle, as the UK Government’s initial reaction to the Deforestation Regulation demonstrates, the potential for SC2 to be met does though clearly exist.

4. Testing the Criteria for applying the Stormont Brake – The Impact Criteria

How often the Stormont Brake might be initiated for an EU act amending or replacing an EU act applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework will depend not only on whether the scope criteria have been met, but also the impact criteria. Three impact criteria would, as noted (see 2.3 above), need to be met. The impact of the EU act as amended or replaced would need to be:

-

- ‘significant’ (IC1);

- ‘specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland’ (IC2); and

- ‘in a way that is liable to persist’ (IC3).

Crucial here is how the three criteria will be interpreted. However, Article 13(3a) provides no definitions; the same applies to the Windsor Framework (Democratic Scrutiny) Regulations 2024 and the accompanying Explanatory Memorandum. And despite noting the significance of the Stormont Brake and stating that ‘it will ensure that the arrangements and in place to enable [its] full use’, the UK Government’s 2024 Safeguarding the Union Command Paper contains no guidance either. It did, however, include a commitment to update guidance so that government departments would provide ‘proper analysis on how a proposed act might affect Northern Ireland’s people, businesses, and place in the UK internal market’.

In the absence of any definition of the three impact criteria, either individually or collectively, MLAs seeking to initiate the use of the Stormont Brake appear set to have the first opportunity to offer a definition of the criteria. Whether the UK Government in considering a notification will adopt the same definition remains to be seen.

The next question is the extent to which the criteria would be met and whether this can be demonstrated. Brief consideration of the Deforestation Regulation, assuming it would have met the two scope criteria, can provide some insights into the challenges involved.

The key requirement of the Deforestation Regulation is that companies importing or exporting seven specific commodities (cocoa, coffee, soy, palm oil, wood, rubber, and cattle) and their derivatives as well as products made using these commodities (e.g. leather, cosmetics, chocolate etc.) prove the products are deforestation-free. As such the Regulation will clearly have an impact on companies in Northern Ireland purchasing and selling the commodities and products covered and for those companies the impact may be ‘significant’ depending on how the impact is measured. Many products used on a day-to-day basis would be covered, but would this be in a way that is ‘specific’ to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland’? It could be if the affected products are supplied primarily from Great Britain and those suppliers cannot or are unable to prove their deforestation-free origin.

Assuming this were the case, then the question arises whether the impact would be ‘liable to persist’. This would depend on whether similar deforestation-free legislation is adopted in the rest of the UK such that producers and suppliers would be obliged to verify deforestation-free origins of goods and, if not, whether supplies of the goods for the Northern Ireland market could be sourced from elsewhere. In this respect, it is worth noting that the UK Government is committed to introducing ‘due diligence’ requirements for businesses regarding ‘forest risk commodities’ in goods. And in December 2023, it set out plans for new regulations stating that these would ‘focus on four commodities identified as key drivers of deforestation: cattle products (excluding dairy), cocoa, palm oil and soy’. While the proposed scope of the new UK deforestation regulations will probably be narrower than in the EU’s Deforestation Regulation, similar regulatory requirements would weaken a case that the impact was ‘significant’ and ‘specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland in a way that is liable to persist’.

Consideration of whether the Deforestation Regulation could have been subject to the Stormont Brake is academic. The Northern Ireland Assembly was not sitting in 2023 and so the Stormont Brake was not available to be used. The EU’s Deforestation Regulation therefore now applies in Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Consideration does, however, highlight the challenge in making a clear case for the activation of the Stormont Brake.

5. And if the UK Government does apply the Stormont Brake, what next?

If the UK Government decides to apply the Stormont Brake it notifies the European Commission, and the application of the relevant EU act is suspended. Although the European Commission may request within two weeks further explanation from the UK Government for its decision, it cannot block the suspension of the EU act. If it does seek further explanation, the suspension of the relevant EU act is deferred until the UK Government has responded, which it must do within two weeks.

This then begs the question of what the EU could do next. It could simply accept the non-application of the relevant amending or replacement act. Much will depend here on, among other things, the strength of the case of applying the Stormont Brake and whether the act’s non-application poses a threat to the integrity of the EU internal market.

Alternatively, the EU could inform the UK that the relevant act falls within the scope of the Protocol/Windsor Framework and propose that it be added to Annex 2 through a Decision of the EU-UK Joint Committee in accordance with Article 13(4). If it does, the UK Government has committed to ‘intensive consultations’ in the Joint Committee. However, the UK Government would normally only be able to agree to the relevant EU act being added if the addition has cross-community support of MLAs through an ‘applicability motion’ of the Assembly. Ultimately, if there is no agreement on adding the relevant EU act to Annex 2, the EU could take ‘appropriate remedial measures’. These could ultimately involve suspension of Northern Ireland’s access to the EU internal market, at least for specific goods.

A further option is for the EU to challenge the UK Government’s use of the Stormont Brake. The matter would not be considered by the EU Court of Justice, but under the independent arbitration procedure provided for Article 175 of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement. If its arbitration panel rules that the criteria for applying the Stormont Brake have not been met, the UK Government has agreed to the application of the relevant amending or replacement act within two months of the panel’s ruling.

Conclusion

The Stormont Brake exists to provide an opportunity for UK Government to block the application of certain EU laws under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Central to the process is the Northern Ireland Assembly. Only through the action of MLAs can the process be initiated. If 30 MLAs agree that the criteria for applying the Brake have been met, the Speaker will notify the UK Government. If the UK Government agrees with the MLAs, it will activate the Brake.

The scope of the Stormont Brake’s application is limited. It cannot be used to disapply EU legislation that already applies under the Protocol Windsor Framework. Moreover, its application is limited to EU acts that ‘amend’ or ‘replace’ EU acts already applicable under Protocol/Windsor Framework, and to acts governing goods accessing the EU internal market. Certain acts are, however, excluded. With the application of the Stormont Brake limited to only EU acts that ‘amend’ or ‘replace’ EU acts already applicable under Protocol/Windsor Framework means, the majority of EU acts automatically applying as part of the process of dynamic regulatory alignment – implementing acts – are by definition out of scope.

Based on analysis of the EU acts adopted in 2023 and applying as part of the process of dynamic regulatory alignment, not many EU acts will meet the scope criteria. Some will, and indeed there will be periods when the EU’s legislative activity will be greater than in 2023, thus increasing the likelihood of there being amending and replacement EU acts that could potentially be subject of the Stormont Brake process.

Importantly, where acts do meet the scope criteria, three impact criteria need to be met before the Stormont Brake can be activated. As yet, no guidance has been given as to how the criteria – ‘a significant impact specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland in a way that is liable to persist’ (emphasis added) – are to be defined, and use of the Stormont Brake has not been tested. What is clear is that evidencing the impact will not necessarily be a straightforward exercise. This not only reflects the substance of the criteria, but also the procedural requirements that MLAs need to fulfil in initiating the Stormont Brake process.

Ultimately, MLAs will not decide whether the Stormont Brake will be applied. The decision falls to the UK government as to whether the criteria have been demonstrably met, the MLAs have provided a ‘valid’ notification, and whether it will therefore apply the Brake.

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Note:

1. One EU act, Regulation (EU) 2023/1182 concerning medicinal products for human use intended to be placed on the market in Northern Ireland would normally have fallen within scope of Article 13(3a). However, although it does amend an EU act applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework (Directive 2001/83/EC), the Regulation was added to Annex 2 following UK-EU agreement under Article 13(4) in the EU-UK Joint Committee as part of the agreement on the Windsor Framework.