Democratic Consent and the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland

David Phinnemore and Lisa Claire Whitten

June 2022 (Updated)

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Introduction

An important – and indeed novel – feature of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland is the ‘democratic consent mechanism’. It commits the UK government to provide members of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLAs) with the opportunity to grant their consent to the continued application of core provisions of the Protocol. These provisions – Articles 5-10 of the Protocol – concern primarily arrangements for the free movement of goods on the island of Ireland and therefore the location of post-Brexit customs and regulatory checks. These are the checks that currently are – or should be – taking place at ports and airports in Northern Ireland. An initial ‘democratic consent’ vote is scheduled to take place in November/December 2024.

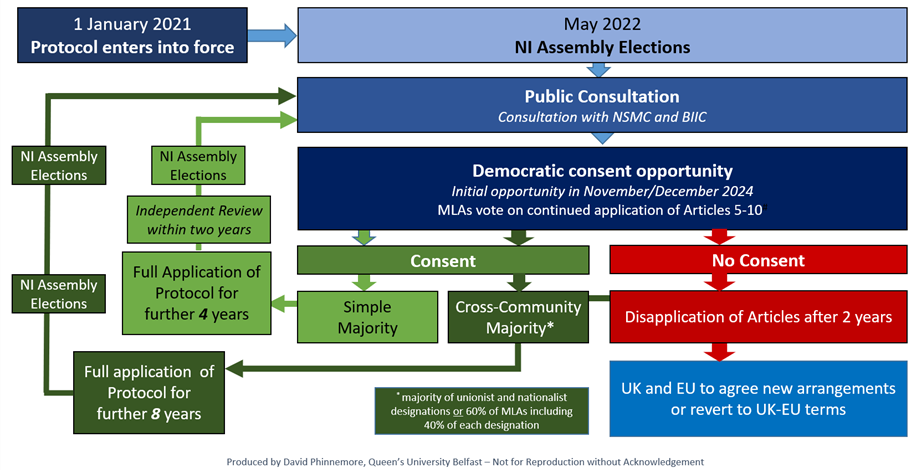

Assuming MLAs grant consent, they will be provided with a further opportunity to vote on Articles 5-10 of the Protocol after four or eight years depending on whether their most recent vote in favour of consent was by a simple majority or involved a cross-community majority. Where a democratic consent vote is held, and there is no majority in favour of consent, Articles 5-10 of the Protocol cease to apply after two years. In the meantime, the UK and the EU will, as required by the Protocol, take ‘necessary measures, considering the obligations of the parties to the 1998 [Belfast (Good Friday)] Agreement’.

The existence of the democratic consent mechanism therefore provides an opportunity for democratic input into the continued existence of the Protocol’s core provisions on the movement of goods. It also means, however, that the medium- to long-term future of arrangements for the movement of goods in and out of Northern Ireland remains uncertain. The outcome of the 2024 vote – as well as any democratic consent votes thereafter – will therefore be of vital importance for Northern Ireland as well as for the UK as a whole, for Ireland, for UK-Ireland relations and for UK-EU relations.

The existence of the democratic consent mechanism raises a range of questions. Why is such a mechanism included in the Protocol, and what does the mechanism involve? How will MLAs vote in 2024? What happens if there is no Northern Ireland Executive in place and the Northern Ireland Assembly is not meeting? What happens if MLAs do not consent for Articles 5-10 of the Protocol to continue to apply? And when will there next be an opportunity for MLAs to vote if a majority of MLAs do vote in favour of Articles 5-10 continuing to apply?

This explainer considers these and other questions regarding the democratic consent mechanism.[1] A first section provides background on the mechanism’s presence in the Protocol. A second section considers the legal and political texts that underpin the democratic consent mechanism. A third section reviews in more detail the participants in, and the substance and anticipated timing of a democratic consent vote. A fourth section sets out the different outcomes. A fifth section tracks the development of the domestic law procedure for the exercise of democratic consent as provided for in the Protocol. Following this, the sixth and seventh sections detail the mechanics of the two processes – ‘default’ and ‘alternative’ – established in UK law for MLAs to vote on whether to grant consent for the continuation of Articles 5-10 of the Protocol. Sections eight and nine then set out the implications of, respectively, a vote granting consent for and a vote against the continued application of these provisions of the Protocol.

1. Why a Democratic Consent Mechanism?

The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland places Northern Ireland in a unique position in the UK-EU relationship. Although formally ‘part of the customs territory of the United Kingdom’ (Article 4) and occupying an ‘integral place in the [UK] internal market’ (Article 6(2)), the effect of the Protocol is to make Northern Ireland part of the EU’s customs territory and internal market for goods. This follows from core provisions of the Protocol applying in Northern Ireland the EU Customs Code and specified EU acts providing for the free movement of goods. Moreover, the Protocol requires that amendments and replacements to those EU acts automatically apply in Northern Ireland and includes provisions for relevant new EU laws to be applied by agreement between the UK and the EU (Article 13). Also applicable in Northern Ireland are specified EU acts relating to VAT and excise (Article 8), wholesale electricity markets (Article 9) and state aid (Article 10). Furthermore, for disputes concerning the application of applicable EU law relating to the movement of goods, the United Kingdom in respect of Northern Ireland falls under the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) in Luxembourg (Article 12).

The purpose of these – and other – arrangements in the Protocol is to deliver on a set of shared UK and EU objectives agreed as part of the Brexit process and the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. The objectives are listed in Article 1(3) of the Protocol:

‘to address the unique circumstances on the island of Ireland, to maintain the necessary conditions for continued North-South cooperation, to avoid a hard border and to protect the 1998 [Belfast/Good Friday] Agreement in all its dimensions’

When the UK government under Theresa May agreed to the initial ‘backstop’ version of the Protocol as part of the initial 2018 Withdrawal Agreement, there was no provision for any ‘consent’ mechanism, whether for the entry into force of the ‘backstop’ Protocol and its differentiated arrangements for Northern Ireland – albeit ones that would have kept the UK as a whole in a customs union with the EU – or for their continued application.

For some critics of this ‘backstop’ version of the Protocol, the absence of a consent mechanism ran counter to the spirit if not necessarily the letter of the 1998 Agreement, a central element of which is the principle of consent. This principle is reflected the requirement for the people of Northern Ireland to give their consent for any change in the constitutional status of Northern Ireland – i.e. Northern Ireland leaving the United Kingdom for a united Ireland – and the provisions regarding a ‘petition of concern’ according to which certain legislation can only be adopted by the Northern Ireland Assembly where there is ‘cross-community’ support among the MLAs. The ‘backstop’ Protocol was therefore perceived by some as a breach of the 1998 Agreement. Others were not convinced.

Opposition to the differentiated treatment of Northern Ireland and criticism of the absence of any consent mechanism for the Protocol were among the reasons why the May government was unable during the first half of 2019 to secure support for the 2018 version of the Withdrawal Agreement concluded with the EU. May’s successor as Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, took up the issue and in August 2019 insisted that the ‘backstop’ Protocol was ‘anti-democratic’ and could not form part of any agreed terms governing the withdrawal from the EU.

Despite the implied rejection of differentiated treatment for Northern Ireland, Johnson conceded that regulatory alignment between Northern Ireland and the EU was necessary to avoid a hard border. This could be acceptable provided that arrangements would be subject to the consent of MLAs ‘before they enter into force… and every four years afterwards’. As the UK government noted in its proposals for revisions to the ‘backstop’ Protocol:

‘Northern Ireland will be, in significant sectors of its economy, governed by laws in which it has no say. That is clearly a significant democratic problem. For this to be a sustainable situation, these arrangements must have the endorsement of those affected by them, and there must be an ability to exit them. That means that the Northern Ireland institutions – the Assembly and the Executive – must be able to give their consent on an ongoing basis to this zone (and to the Single Electricity Market, which raises similar issues)’.

With the Irish government open to the inclusion of a consent mechanism, the EU agreed to revise the Protocol. However, it rejected the UK government’s proposal that a consent vote would be required for the Protocol to enter into force. It also sought to reduce the frequency of votes given that the Protocol was designed, in part at least, to minimize uncertainty around arrangements for avoiding a hard border. The result is the democratic consent mechanism provided for in Article 18 of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland annexed to the Withdrawal Agreement concluded by the UK government with the EU in October 2019 and which entered into force on 31 January 2020.

2. Providing for Democratic Consent

The arrangements for democratic consent are set out in three documents.

The first is the Protocol itself, where Article 18 (see Annex 1 below) states that ‘the United Kingdom shall provide the opportunity for democratic consent in Northern Ireland to the continued application of Articles 5 to 10’. A first ‘opportunity’ will be before the end of the fourth year of the Protocol’s application, i.e. before the end of 2024. In providing such an opportunity, the United Kingdom ‘shall seek democratic consent… in a manner consistent with the 1998 Agreement’ (emphasis added). Article 18 then sets out what happens if consent is not provided. We discuss this more below (see section 9), but essentially Articles 5-10 will cease to apply after two years. In the meantime, the Joint Committee overseeing implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement – and with it the Protocol – will make recommendations to the UK and the EU on ‘necessary measures’. Where, however, Articles 5-10 continue to apply, Article 18 states that a further opportunity for democratic consent will be provided after four years where there is a simple majority of MLAs providing consent or eight years where there is ‘cross-community support’ (see below, section 4).

Article 18 also refers to a second document. This is the Declaration by Her Majesty’s Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning the operation of the ‘Democratic consent in Northern Ireland’ provision of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland. The document was issued on 17 October 2019 (see Annex 2 below). And its importance cannot be understated. Although only a political statement, according to Article 18, any ‘decision expressing democratic consent shall be reached strictly in accordance with the unilateral declaration’. The Declaration sets out how the UK government will provide the opportunity for democratic consent and what the process will entail. It also contains a ‘commitment to legislate for a democratic consent process’ (see below, section 5).

The third document follows from this commitment and is Statutory Instrument 2020/1500. Entitled The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland (Democratic Consent Process) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/1500), it sets out in an amendment to the Northern Ireland Act 1998 the arrangements for democratic consent. Statutory Instrument (SI) 2020/1500 was made on 9 December 2020 under powers granted to UK government ministers by the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. It was therefore adopted without a debate on the floor of the House of Commons. It was, however, considered and approved by eleven MPs sitting on the Delegated Legislation Committee of the House of Commons on 26 November 2020. Their deliberations lasted just 16 minutes. There was no consultation or impact assessment and no MPs from Northern Ireland participated in the approval. The Grand Committee of the House of Lords gave the matter greater consideration on 1 December 2020 during a 50 minute-long debate involving several members from Northern Ireland. It agreed to the motion approving the SI.

The SI inserts a new section 56A and new Schedule 6A into the Northern Ireland Act 1998. In doing so, it establishes the legal basis for delivering ‘the opportunity for democratic consent in Northern Ireland’ provided for in Article 18 of the Protocol and the accompanying UK government Declaration.

Together these three documents set out how and when the democratic consent mechanism will operate.

3. Who votes… on what… and when?

The democratic consent mechanism provides the elected members of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLAs) with an opportunity to vote – potentially as often as every four years – on whether Articles 5-10 of the Protocol shall continue to apply.

There are several points to note here.

First, the democratic consent mechanism applies to a specific set of provisions in the Protocol, primarily those covering the regulatory alignment that allows for the free movement of goods between Northern Ireland and the EU, thereby avoiding a physical hardening of the land border on the island of Ireland. Also covered is the regulatory alignment allowing for the continued free flow of electricity supply on the island of Ireland. As such the democratic consent mechanism does not provide MLAs with a formal opportunity to ‘scrap the Protocol’ as is often mistakenly assumed.[2] MLAs only vote on Articles 5-10.

The democratic consent mechanism does not apply to the Protocol’s objectives (Article 1) or its provisions on, for example, the rights of individuals (Article 2), the Common Travel Area (Article 3), continued North-South cooperation beyond the movement of goods and the Single Electricity Market (Article 11) implementation and governance arrangements (Articles 12-15).

Second, Articles 5-10 come as a package; MLAs do not vote on whether they wish to see individual provisions retained. For example, MLAs cannot in a democratic consent vote per se opt to retain Article 9 on the Single Electricity Market while withholding consent for the continued application of the remaining articles.

Third, it is not the ‘consent of the people of Northern Ireland’ per se that is being sought, but the consent of their elected representatives in the Northern Ireland Assembly. MLAs can be expected to vote, however, on the positions advanced in Assembly elections. Given the five-year cycle for Assembly elections and assuming consent is only by a simple majority of MLAs, four in every five future elections could become a proxy vote for the continued application of Articles 5-10 of the Protocol and indeed for the principle of the Protocol as a whole. Among the likely effects, therefore, of the democratic consent mechanism, particularly given divided reactions to the Protocol are sustained political contestation and indeed business and other stakeholder uncertainty regarding continued application of its core provisions.

Fourth, following an initial vote scheduled for late 2024, and assuming consent is granted, the next opportunity to hold a democratic consent vote will be after eight years if there is ‘cross-community’ consent or after four years if consent is granted by a simple majority of MLAs voting. Of note too is that democratic consent votes are not mandatory under the Protocol. The reference in Article 18 is to the UK government providing an ‘opportunity’ for democratic consent vote. Whether a vote will be held will depend on decisions taken by the Northern Ireland Executive and MLAs; it is indeed technically possible that MLAs may decide not to hold a vote (see below, sections 5 and 6).

4. What does consent look like?

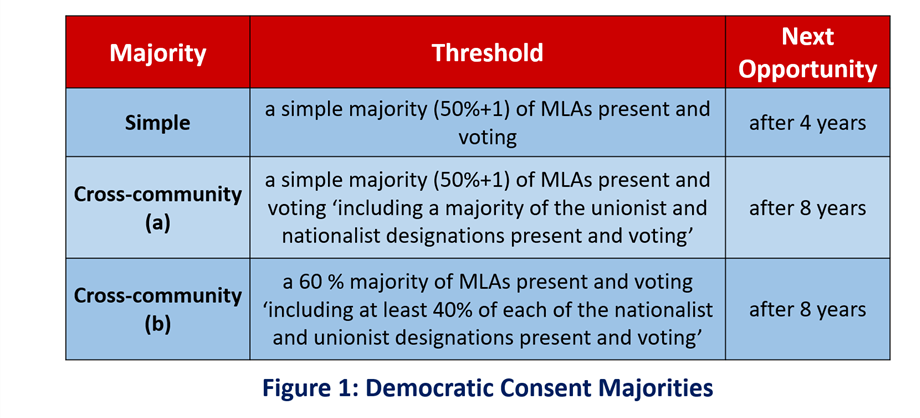

Democratic consent come in two forms: consent by a simple majority or consent with a cross-community majority. Which form of majority is achieved is important since it determines when the democratic consent mechanism can next be used. The requirements of each majority are set out in Article 18 and in Schedule 6A of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

The first type of majority – a ‘simple’ majority – requires 50%+1 of the MLAs present and voting to support a ‘motion for consent’ (see Figure 1). To note here is that the Speaker (or Deputy Speaker), as presiding officer, does not have a vote in Assembly debated. Therefore, if 86 of the 89 MLAs eligible to vote took part in a democratic consent vote, a simple majority would be 44 MLAs (43+1). If there is an even number of MLAs present and the vote splits 50-50 then the motion is not carried and so there would be no consent. If a simple majority is secured, the next democratic consent opportunity will be after four years.

The second type of majority – a ‘cross-community’ majority – can be secured through two routes:

- a simple majority (50%+1) of MLAs present and voting where this includes a majority of designated unionists and a majority of designated nationalists

- a 60% majority of MLAs present and voting where this includes 40% of designated nationalists and 40% of designated unionists

The exact number of MLAs required to meet the majorities required for cross-community consent will depend on how many MLAs designate as ‘nationalist’ and ‘unionist’. During the 2017-22 Assembly there were 39 MLAs who designate as ‘nationalist’ and 40 MLAs as ‘unionist’. The remaining 11 MLAs either designated as ‘other’ or were deemed to have designated themselves so. The votes of these ‘other’ MLAs contribute to the 50%+1 and the 60% majority requirements but play no role in the remainder of the calculation for a cross-community majority. The thresholds are the same as those that apply when MLAs vote on legislative matters requiring ‘cross-community support’, for example following a petition of concern. If a cross-community majority is secured, the next democratic consent opportunity will be after eight years.

Claims have been made that the option of democratic consent being granted by a simple majority of MLAs and without cross-community support contravenes the spirit, if not the letter, of the principle of consent at the heart of the 1998 Agreement. This is primarily because MLAs cannot lodge a ‘petition of concern’ and so require a consent vote to include a dual majority of designated nationalists and designated unionists.[3]

To have required a dual majority would have been to grant each ‘community’ a veto over the continued application of Articles 5-10 of the Protocol. In devising the Protocol to address the ‘significant and unique challenge to the island of Ireland’ that the UK’s withdrawal from the EU presented, the UK and the EU were intent on minimizing as far as they could the anticipated disruptive effects of Brexit and securing as much certainty as possible for Northern Ireland. To have allowed MLAs from one ‘community’ to prevent the continued application of the Protocol would have been to compromise efforts at promoting certainty.

5. From ‘opportunity for democratic consent’ to a democratic consent vote

Although Article 18 provides only that the UK ‘provide the opportunity for democratic consent’, it is widely expected that a first democratic consent vote will be held in 2024. This is not only the consequence of how the Protocol has been presented in the UK Declaration, but also how UK legislation governing the use of the democratic consent mechanism has been written to include contingencies for a situation where there is no functioning Northern Ireland Executive, and the Northern Ireland Assembly is not meeting. Essentially, absent a functioning Executive, a democratic consent vote by MLAs will be held in November/December 2024.

The 2019 UK Declaration on the democratic consent mechanism expands on Article 18 and sets out the UK approach to the mechanism. Overall the UK objective:

‘should be [NB not ‘is’] to achieve agreement that is as broad as possible in Northern Ireland and, where possible, through a process taken forward and supported by a power sharing Northern Ireland Executive’

Moreover, that process is to follow ‘a thorough process of public consultation’ undertaken by the Northern Ireland Executive’. This, according to the UK Declaration will see the UK government:

‘provide support as appropriate to the Northern Ireland Executive in consulting with businesses, civil society groups, representative organisations (including of the agricultural community) and trade unions on the democratic consent decision’.

The UK Declaration also states that the North South Ministerial Council and British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference ‘should [NB not ‘shall’] be involved in any consultation process’.

The mechanics of the democratic consent process were refined and, with the exception of the arrangements for public consultation, given legal effect through SI 2020/1500 and the introduction of Schedule 6A to the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (see above, section 2)

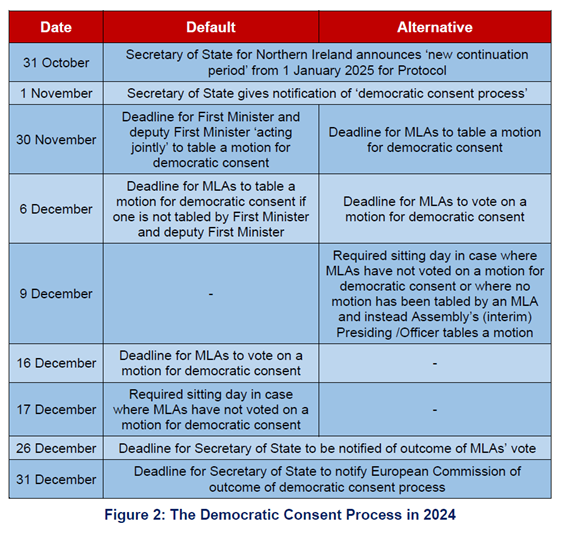

Schedule 6A involves the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland initiating the democratic consent process two months before the end of 2024 following a formal announcement of a ‘continuation period’ for the Protocol. Assuming consent in 2024, the democratic consent process will thereafter be initiated by the Secretary of State immediately after the next ‘continuation period’ is announced two months before the end of the four- or eight-year period depending on the nature of the majority in favour of consent. If in 2024 consent is granted by a simple majority of MLAs, the next opportunity for a democratic consent vote will be in November/December 2028. If there is a cross-community majority, the next opportunity for a democratic consent vote will be in November/December 2032.

In addition to this ‘default’ process, Schedule 6A includes an ‘alternative democratic consent mechanism’. The provisions apply if, on the day the Secretary of State initiates the democratic consent period, ‘the offices of the First Minister and the deputy First Minister are vacant (and their functions are not otherwise being exercised by another Northern Ireland Minister in accordance with section 16A(11))’. There is thus a contingency for if Northern Ireland is without an Executive.

And, thereafter, it is the UK government’s position that the ‘consent process… will be repeated every four or eight years’ (emphasis added).

6. The ‘Default Democratic Consent Process’

For a consent vote to take place, MLAs need to be provided with a ‘motion for a consent resolution’. Under the ‘default democratic consent process’, it falls in the first instance to the First Minister and deputy First Minister in the Northern Ireland Executive ‘acting jointly’ to decide whether to table such a motion. They must act before 30 November. The required wording of the ‘resolution’ for a motion is set out in SI 2020/2500:

‘That Articles 5 to 10 of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland to the EU withdrawal agreement should continue to apply during the new continuation period (within the meaning of Schedule 6A to the Northern Ireland Act 1998)’

If the First Minister and deputy First Minister do table a motion for a consent resolution it must be accompanied ‘with such explanatory materials as it is reasonable to provide in order to assist them when deciding the question’. It is for the First Minister and deputy First Minister to determine what form ‘such explanatory materials’ shall take.

If the First Minister and deputy First Minister do not table a motion, then ‘any’ MLA may do so ‘[b]efore the start of the final 25 days of the current period’, i.e. within the first six days of December. Other MLAs may add their name to the motion. Lack of agreement between First Minister and deputy First Minister on whether to table a motion for a consent resolution cannot therefore prevent a democratic consent vote taking place.

If an MLA tables a motion, it falls to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to take ‘reasonable steps’ to provide MLAs with ‘such explanatory materials as it is reasonable to provide in order to assist them when deciding the question’.

If no motion is forthcoming from an MLA, the democratic consent process ends. Motions tabled and then withdrawn are treated as not having been tabled. In the absence of a motion being tabled, Articles 5-10 continue to apply.

Where a ‘motion for a consent resolution’ is tabled, the vote is organized in line with normal Assembly procedures. However, the vote needs to take place before the start of ‘the final 15 days of the current period’ (i.e. 17 December). Also, the motion is to be adopted without amendment, and there can only be one motion on which MLAs vote.

And Schedule 6A is explicit: ‘Section 42 does not apply in relation to a motion for a consent resolution’. A petition of concern cannot therefore be applied.

If, however, before the start of ‘the final 15 days of the current period’ (i.e. 17 December) MLAs have not held their vote on a tabled motion, provision exists for a ‘required sitting day’. If such a day is necessary, the consent resolution will be the first business of the day. The session will start at noon and MLAs will vote no later than six hours after the motion has been moved and the Assembly may not be adjourned until the result of the vote has been declared. If the motion is not put as required, a further ‘required sitting day’ will be held.[4]

Once the MLAs have voted and the outcome has been declared, the Presiding Officer notifies the Secretary of State of the outcome. This must happen ‘before the start of the final 5 days of the current period’ (i.e. 26 December). The Secretary of State then communicates the outcome to the European Commission on or before 31 December.

The schedule, with dates for the expected 2024 vote, are set out in Figure 2.

7. The ‘Alternative Democratic Consent Process’

The expectation is that the Northern Ireland Executive will be in place whenever MLAs are given an ‘opportunity’ for democratic consent. However, Schedule 6A also provides for an ‘alternative democratic consent process’ if the posts of First Minister and deputy First Minister are vacant.

This alternative process also commences with the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland announcing the continuation period and giving notification of the start of the democratic consent process. The Secretary of State must also provide ‘such explanatory materials as it is reasonable to provide in order to assist [MLAs] when deciding the question on the motion for a consent resolution’.

As soon as the Secretary of State has given notification of the start of the democratic consent process, an MLA may table a motion for a consent resolution. Provided a motion has been tabled, MLAs vote in line with normal Assembly procedure and the outcome is communicated to the Secretary of State.

If no MLA has tabled a motion by the end of the month, however, the Assembly’s Presiding Officer summons MLAs for a ‘required sitting day’ on the first weekday during the final 25 days of the following month. In 2024, this will be Monday 9 December. A ‘required sitting day’ will also be called if MLAs have not voted on a tabled motion.

Where a motion for democratic consent has not been tabled, the ‘alternative’ process requires the Presiding Officer to table such a motion on the ‘required sitting day’. MLAs can then proceed to vote. If no MLA moves the motion, the Presiding Officer must move it so the vote can be taken. As with the ‘default’ process, the consent resolution will be the first business of the day and MLAs will vote no later than six hours after the motion has been moved.[5] The Assembly may not be adjourned until the result of the vote has been declared. If the motion is not put as required, a further ‘required sitting day’ will be held.

Once the MLAs have voted and the outcome has been declared, no further motion can be tabled. The Presiding Officer notifies the Secretary of State of the outcome. As with the ‘default’ process, this must happen ‘before the start of the final 5 days of the current period’ (i.e. 26 December). The Secretary of State then communicates the outcome of the vote to the European Commission on or before 31 December.

8. What happens if MLAs support a democratic consent motion?

If MLAs vote in favour of a democratic consent motion the provisions of Article 5-10 of the Protocol will continue apply and the UK ‘in respect of Northern Ireland’ will remain aligned with EU law applicable under the Protocol.

MLAs will, however, as noted, be given a further opportunity to vote after four or eight years depending on whether the majority in the previous voted was, respectively, a ‘simple’ or a ‘cross-community’ majority.[6] If, under the default democratic consent process, no motion is tabled, and no vote is held, cross-community support for the continued application of Articles 5-10 would be deemed to exist. The next opportunity for a democratic consent vote will be after eight years (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Democratic Consent in 2024 and Beyond

If a democratic consent motion only gains the support of a simple majority of MLAs and so the continued application of Articles 5-10 is for four years, the UK government will commission an independent review into the functioning of the Protocol. This was envisaged in the Unilateral Declaration, the relevant paragraphs of which – paragraphs 7-9 – are specifically referenced in Schedule 6A of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

These envisage a review that looks at ‘the implications of any decision to continue or terminate alignment on social, economic and political life in Northern Ireland’. The review will involve ‘close consultation’ with political parties in Northern Ireland, businesses, civil society groups, representative organisations (including of the agricultural sector) and trade unions. It will conclude within two years of the MLAs’ democratic consent vote – so before the end of 2026 in the case of a simple majority on a motion in 2024 – and make recommendations ‘including with regard to any new arrangements it believes could command cross-community support’.

The independent review will be commissioned by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. Who will undertake the review is not specified.

9. What happens if MLAs do not support a democratic consent motion?

If MLAs do not vote in favour of a democratic consent motion, Article 18(4) of the Protocol states that the provisions of Article 5-10 of the Protocol ‘shall cease to apply after 2 years’.[7] Article 18(4) also states that ‘other provisions… to the extent that [they] depend on [Article 5-10] for their application’ would also cease to apply after two years. For a vote in 2024, this would mean on 31 December 2026. This begs the question: what would replace Articles 5-10?

The default position is that for matters covered by Articles 5-10 the terms of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement would apply. The essential consequence of this would be to subject the movement of goods from Northern Ireland to the EU to the same regime as goods moving from the rest of the UK to the EU. The effect would be to take Northern Ireland out of its current position of being de facto part of the EU customs territory and its internal market for goods and so remove all Protocol-related formalities, checks and controls applicable to goods moving from the rest of the UK into Northern Ireland across the ‘Irish Sea border’ to the land border on the island of Ireland.

While this would restore the conditions for the movement of goods between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, subject to changes in domestic UK legislation, to what they were before the Protocol entered into force on 1 January 2021, it would introduce the respective UK/EU import/export regimes at the land border. It is most likely, that this would necessitate capacity for physical checks and controls at the border. The single electricity market on the island of Ireland would also be disrupted with relevant EU law no longer applying in respect of Northern Ireland. This is the default situation.

What exactly the situation would be after two years would be for the UK and the EU to determine. Just as Article 18(4) provides for Articles 5-10 no longer to apply, so too does it envisage the UK and the EU receiving recommendations from the Joint Committee on what ‘necessary measures’ might be taken. The fact that these would be recommendations of the Joint Committee means that they would be jointly agreed by the UK and the EU. It can be reasonably assumed that the recommendations would then be taken forward and a formal agreement concluded between the UK and the EU governing their adoption and implementation.[8]

Recommendations from the Joint Committee would be ones ‘taking into account the obligations of the parties to the 1998 Agreement’ and ones adopted having potentially sought the views of ‘institutions created by the 1998 Agreement’. The list of institutions that could be consulted would include: the Northern Ireland Executive, the Northern Ireland Assembly, the North-South Ministerial Council, and the British-Irish Council.[9]

Given the continued application of Article 1 of the Protocol, the ‘necessary measures’ would presumably have the same objectives as the Protocol, i.e. ‘to address the unique circumstances on the island of Ireland, to maintain the necessary conditions for continued North-South cooperation, to avoid a hard border and to protect the 1998 Agreements in all its dimensions’. This begs the question as to what those ‘necessary measures’ might be and whether there would be agreement – as there presumably was with the adoption of the Protocol – of what ‘the obligations of the parties to the 1998 Agreement’ are. Of note here, is the absence of a formal and direct ‘obligation’ of Ireland and the UK, as parties to the 1998 Agreement, to avoid a ‘hard border’ on the island of Ireland. Moreover, ‘necessary measures’ need only ‘take account’ of those obligations.

It could be that the UK and EU agree to the re-application of selected provisions, e.g. on maintaining the single electricity market. They could go further. Indeed, it has been suggested that the UK government does not rule out simply making minor alterations to and essentially retaining Article 5-10, although this seems unlikely given that it would be contrary to the position adopted by MLAs.

Whether the UK and the EU could agree new replacement arrangements that deliver on the obligations of the parties to the 1998 Agreement very much depends on the extent to which the two sides are willing to agree measures that manage formalities, checks and controls on the movement of goods across the land border any differently to goods moving across the sea border between the rest of the UK and the EU. And here not only will the EU’s stance on protecting the integrity of its internal market be crucially important, but so too will the position of the UK government at the time to the question of UK regulatory alignment with the EU as far as the movement of goods is concerned. A more pragmatic and less ideological approach than that of the current government of Boris Johnson would reduce the need for separate arrangements to reduce frictions on the movement of goods across the land border if Articles 5-10 of the Protocol were no longer in force.

Essentially, if MLAs do not vote for the continued application of Articles 5-10, the question of the future nature of the land border moves back to 2017-2019 and the debates that led to the emergence and content of the Protocol. At the time, some opponents of the Protocol insisted that technological solutions either existed or, in the case of ‘smart border’ technology, would soon exist. With the latter in mind, negotiators did acknowledge in the preamble to 2018 ‘backstop’ version of the Protocol that they might emerge. The UK and the EU recalled their ‘intention to replace the backstop solution on Northern Ireland by a subsequent agreement that establishes alternative arrangements for ensuring the absence of a hard border on the island of Ireland on a permanent footing’. The recital was not, however, retained in the preamble to the revised version of the Protocol. What was retained was the UK government’s ‘guarantee of avoiding a hard border, including any physical infrastructure or related checks and control’ and the ‘firm commitment’ of the UK and the EU ‘to no customs and regulatory checks or controls and related physical infrastructure at the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland’. The challenge for the UK and the EU following any vote by MLAs that does not grant consent to the continued application of Articles 5-10 of the Protocol will be how to square existing commitments to avoiding a physical hardening of the border on the island with rejection of the Protocol’s arrangements that have allowed them to meet those commitments.

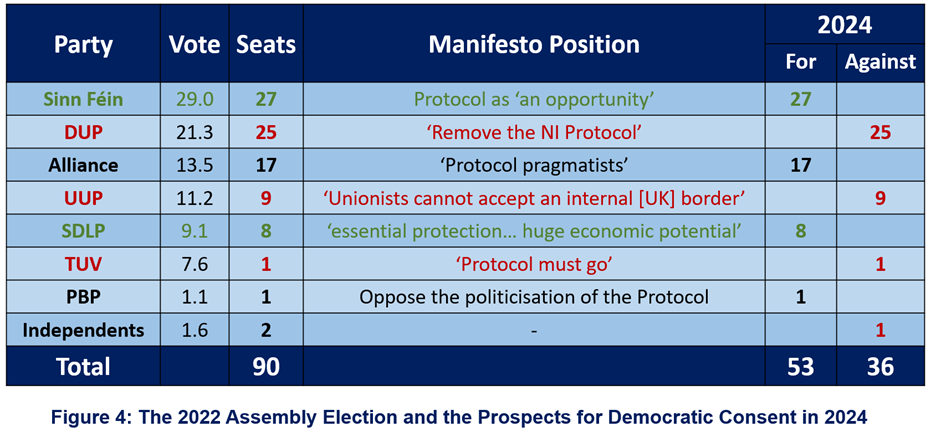

10. The significance of the 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly elections

Elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly took place on 5 May 2022. Each party took a position on the Protocol. Based on election manifestos and public statements, of the 90 MLAs elected 54 are currently likely to vote in favour of continued application of Articles 5 to 10 of the Protocol in 2024. These are MLAs that either designate as ‘nationalist’ (green in Figure 4) or do not designate and are considered as ‘other’ (black in Figure 4). Of the remaining 36 MLAs likely to vote against democratic consent all designate as unionist. The majority would therefore only be a simple majority, and not one based on cross-community consent. MLAs would therefore be offered a further opportunity to vote on Article 5 to 10 of the Protocol in 2028.

If, prior to 2024, outstanding issues are addressed some of those currently seen as likely to vote against may abstain. This would not alter the nature of the majority given no unionist party currently supports the Protocol. Similarly, if the lived experience of the Protocol is sufficiently adverse, some of those currently supportive of the Protocol could change their position, although this seems unlikely to happen. To note is that the Speaker will not have a vote.

In the election, Sinn Féin returned 27 MLAs in the election making it the largest party overall and the first ever nationalist party eligible to nominate a First Minister. In its manifesto, Sinn Féin set out a positive perspective on the Protocol describing it as ‘an opportunity for attracting high-end Foreign Direct Investment, developing new – and expanding existing – local businesses, creating good quality jobs and modernising the economy’. For the second-placed Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which returned 25 MLAs, securing the removal of the Protocol was one of five key priorities going into the election. The DUP manifesto stated: ‘The Protocol must be replaced by arrangements that restore [Northern Ireland’s] place within the UK internal market’ and any new arrangements ‘must command the support of both Unionists and Nationalists’.

The centrist Alliance Party which came third and secured 17 seats in the new Assembly, took the position that the Protocol is ‘imperfect’ but an ‘inevitable consequence’ of the type of Brexit pursued by the UK government. Their Manifesto described the Alliance as ‘Protocol pragmatists’ and advocated making the Protocol work for the benefit of Northern Ireland. The fourth largest party in the Assembly, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) opposed the Protocol and advocated for ‘common sense alternatives’ which would ‘ensure there will be no checks on goods travelling GB-NI that will be staying in Northern Ireland’. The UUP returned nine MLAs to the new Assembly. The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), with eight MLAs, presented the Protocol as providing ‘essential protections for the island of Ireland’ and offering Northern Ireland ‘huge economic potential’.

The party most stridently opposed to the Protocol was the Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) which insisted that ‘the Protocol must go’. It returned one MLA, as did the non-aligned, pro-Irish Unity People Before Profit (PBP) party. Its manifesto focused on criticising the DUP for using the Protocol ‘to polarise politics’.

Concluding remarks

The provisions on democratic consent in the Protocol on Ireland/Northern are unique. Building on the principle of consent that underpins the 1998 Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement, they introduce a mechanism whereby MLAs can determine on a regular basis whether core provisions of an international legal text – the Protocol – designed to avoid a post-Brexit hardening of the physical border on the island of the Ireland should continue to apply. The democratic consent mechanism therefore breaks new ground in the UK constitutional context by providing MLAs with a vote on excepted matters, namely, relations with the EU. The democratic consent mechanism is also novel from an EU law perspective in that it enables a sub-state legislature in a non-member state to take a decision that has legal implications for the geographical extent of the EU internal market for goods and the application of the EU Customs Code.

The democratic consent mechanism clearly draws on the spirit of the principle of consent contained in the 1998 Agreement. By providing for four-year periods between votes passed by ‘simple majority’ and eight-year periods between votes passed by ‘cross-community majority’, the mechanism places a greater premium on ‘cross-community’ consent but importantly does not require it to be achieved for the continued application of all the provisions of the Protocol.

The inclusion of the democratic consent mechanism in Article 18 of the Protocol therefore provides MLAs in Northern Ireland from 2004 with an important role in the future of the arrangements that the UK and the EU agreed in 2019 for post-Brexit Northern Ireland, notably to avoid a physical hardening of the land border. That role is limited, however, to determining whether Articles 5-10 of the Protocol – and so the arrangements that avoid a physical hardening of the border and maintain the single electricity market on the island of Ireland – should continue to apply or not. Article 18 is not a means therefore to remove the Protocol in its entirety.

Provisions relating to the rights of individuals, the Common Travel Area, and north-south cooperation will continue to apply irrespective of the outcome of a democratic consent vote. Article 1 on the objectives of the UK and the EU in agreeing the content of Protocol will also continue to apply, as will provisions on regarding governance arrangements for the operation of the Protocol. The removal of Articles 5-10 would, however, strip the Protocol of much of its regulatory content and, to a significant degree, the more contested elements of its governance arrangements (e.g. dynamic regulatory alignment, jurisdiction of the CJEU). With this, the differentiated treatment of Northern Ireland within the post-Brexit UK-EU relationship would be dramatically reduced. However, the withholding of consent through the democratic consent mechanism is no cure all. Disapplication of Articles 5-10 forces the UK and the EU back to addressing one of the most significant challenges of Brexit: how to avoid a hard land border on the island of Ireland and the economic, political and social consequences that would entail.

June 2022 (updated)

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Annex 1

Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland

Article 18 Democratic consent in Northern Ireland

1. Within 2 months before the end of both the initial period and any subsequent period, the United Kingdom shall provide the opportunity for democratic consent in Northern Ireland to the continued application of Articles 5 to 10.

2. For the purposes of paragraph 1, the United Kingdom shall seek democratic consent in Northern Ireland in a manner consistent with the 1998 Agreement. A decision expressing democratic consent shall be reached strictly in accordance with the unilateral declaration concerning the operation of the ‘Democratic consent in Northern Ireland’ provision of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland made by the United Kingdom on 17 October 2019, including with respect to the roles of the Northern Ireland Executive and Assembly.

3. The United Kingdom shall notify the Union before the end of the relevant period referred to in paragraph 5 of the outcome of the process referred to in paragraph 1.

4. Where the process referred to in paragraph 1 has been undertaken and a decision has been reached in accordance with paragraph 2, and the United Kingdom notifies the Union that the outcome of the process referred to in paragraph 1 is not a decision that the Articles of this Protocol referred to in that paragraph should continue to apply in Northern Ireland, then those Articles and other provisions of this Protocol, to the extent that those provisions depend on those Articles for their application, shall cease to apply 2 years after the end of the relevant period referred to in paragraph 5. In such a case the Joint Committee shall address recommendations to the Union and to the United Kingdom on the necessary measures, taking into account the obligations of the parties to the 1998 Agreement. Before doing so, the Joint Committee may seek an opinion from institutions created by the 1998 Agreement.

5. For the purposes of this Article, the initial period is the period ending 4 years after the end of the transition period. Where the decision reached in a given period was on the basis of a majority of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly, present and voting, the subsequent period is the 4 year period following that period, for as long as Articles 5 to 10 continue to apply. Where the decision reached in a given period had cross-community support, the subsequent period is the 8-year period following that period, for as long as Articles 5 to 10 continue to apply.

6. For the purposes of paragraph 5, cross-community support means:

(a) a majority of those Members of the Legislative Assembly present and voting, including a majority of the unionist and nationalist designations present and voting; or

(b) a weighted majority (60 %) of Members of the Legislative Assembly present and voting, including at least 40 % of each of the nationalist and unionist designations present and voting.

Annex 2

Declaration by Her Majesty’s Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning the operation of the ‘Democratic consent in Northern Ireland’ provision of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland

The United Kingdom recalls its obligation under Article 18 of the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland to provide the opportunity for democratic consent in Northern Ireland to the continued application of certain provisions in that Protocol in a manner consistent with the 1998 Agreement. It notes that under that Article, the modalities for determining democratic consent must be in accordance with this declaration.

The notification to the European Union of the outcome of the democratic consent processes under Article 18 of the Protocol is a matter for the Government of the United Kingdom under paragraph 3 of Schedule 2 to the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

The United Kingdom affirms that the objective of the democratic consent process set out below should be to seek to achieve agreement that is as broad as possible in Northern Ireland and, where possible, through a process taken forward and supported by a power sharing Northern Ireland Executive which has conducted a thorough process of public consultation. This should include cross-community consultation, upholding the delicate balance of the 1998 Agreement, with the aim of achieving broad consensus across all communities to the extent possible.

The United Kingdom Government will provide support as appropriate to the Northern Ireland Executive in consulting with businesses, civil society groups, representative organisations (including of the agricultural community) and trade unions on the democratic consent decision. Where the democratic consent process is operating under the alternative process provided for in paragraph 5, the United Kingdom Government will provide support as appropriate to Members of the Legislative Assembly in consulting with businesses, civil society groups, representative organisations (including of the agricultural community) and trade unions on the democratic consent decision. The North South Ministerial Council and British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference should be involved in any consultation process.

The United Kingdom affirms that the process for affording or withholding consent does not have any bearing on or implications for the constitutional status of Northern Ireland, which is set out in the 1998 Agreement and remains wholly unaffected by the Withdrawal Agreement. The United Kingdom remains able to make further provision for the role of the Northern Ireland Executive and Assembly within its own constitutional arrangements, and providing these are without prejudice to this declaration, the Withdrawal Agreement and the 1998 Agreement.

Commitment to legislate for a democratic consent process

1. The United Kingdom undertakes to reflect as necessary in the legislation of the United Kingdom the commitments in respect of the democratic consent mechanism set out in this Declaration in advance of the date on which notice is first provided under paragraph 2, including in respect of the independent review set out in paragraph 7.

Transmission of the notice

2. The United Kingdom Government will give two months’ written notice to the First Minister and deputy First Minister, the Presiding Officer, and / or the Clerk to the Northern Ireland Assembly of each date on which the United Kingdom will provide notification to the European Union as to whether there is democratic consent in Northern Ireland to the continued application of Articles 5 to 10 of the Protocol. Democratic Consent Process.

3. The United Kingdom undertakes to provide for a Northern Ireland democratic consent process that consists of:

(a) A vote to be held in the Northern Ireland Assembly on a motion, in line with Article 18 of the Protocol, that Articles 5 to 10 of the Protocol shall continue to apply in Northern Ireland.

(b) Consent to be provided by the Northern Ireland Assembly if the majority of the Members of the Assembly, present and voting, vote in favour of the motion.

(c) The Northern Ireland Assembly notifying the United Kingdom Government of the outcome of the consent process no less than 5 days before the date on which the United Kingdom is due to provide notification of the consent process to the European Union.

4. The United Kingdom will make provision such that if the motion for the purpose of paragraph 3(a) has not been proposed by the First Minister and deputy First Minister, acting jointly, within one month of the written notice in paragraph 2 being given, the motion can instead be tabled by any Member of the Legislative Assembly. Where the motion for the purpose of paragraph 3(a) has been proposed by the First Minister and deputy First Minister the Northern Ireland Executive should consider the matter in line with normal practice and procedure, including providing the Assembly with explanatory materials as appropriate.

Alternative process

5. The United Kingdom will provide for an alternative democratic consent process in the event that it is not possible to undertake the democratic consent process in the manner provided for in paragraphs 3 and 4.

6. The alternative process referred to in paragraph 5 will make provision for democratic consent to be provided by Members of the Legislative Assembly if the majority of the Members of the Legislative Assembly, present and voting, vote in favour of the continued application of Articles 5 to 10 of the Protocol on Northern Ireland and Ireland in a vote specifically arranged for this purpose. This alternative process will also provide for the United Kingdom Government to be notified of the outcome of the consent process.

Independent review

7. In the event that any vote in favour of the continued application of Articles 5 to 10 of the Protocol, held as part of the democratic consent process or alternative democratic consent process, is passed by a simple majority in line with paragraph 3b rather than with cross community support, the United Kingdom Government will commission an independent review into the functioning of the Northern Ireland Protocol and the implications of any decision to continue or terminate alignment on social, economic and political life in Northern Ireland.

8. The independent review will make recommendations to the Government of the United Kingdom, including with regard to any new arrangements it believes could command cross-community support.

9. The independent review will include close consultation with the Northern Ireland political parties, businesses, civil society groups, representative organisations (including of the agricultural sector) and trade unions. It will conclude within two years of the vote referred to in paragraph 7 above.

17 October 2019

Notes

- See also the discussion of the democratic consent mechanism in: Curtis, J. et al ‘The October 2019 EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement’, House of Commons Library Briefing Paper, CBP 8713, 17 October 2019; Sargeant, J. Northern Ireland Protocol: consent mechanism, Institute for Government, London, 1 March 2021.

- The formal route for removing the Protocol is through Article 13(8). It provides for the disapplication of the Protocol ‘in whole or in part’ through one or more agreements governing the UK-EU relationship’. It is through such agreements that the UK and the EU will agree ‘those provisions of the Protocol that [the agreement(s)] supersede and whether the Protocol ceases to apply’. In theory, when the UK was negotiating its Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU during 2020, it could have sought to agree arrangements that would have removed the need for all or some of the Protocol’s provisions. In this respect the arrangements would have had to have delivered on the objectives of the Protocol as set out in Article 1(3) (see above). There is, however, no evidence to suggest that the UK government even attempted during the negotiations to make use of Article 13(8) and agree arrangements that could have seen at least some of the Protocol’s provisions disapplied.

- See the criticisms, for example, from the Democratic Unionist Party which has claimed that the democratic consent mechanism ‘goes against the Belfast Agreement’ because continuation of the Protocol does not require the consent of a majority of unionist and nationalist MLAs. Such criticisms were raised in Allister and Others where the Appeal Court in Northern Ireland ruled against the claimants on the grounds that the democratic consent mechanism concerned international relations and was outside the competence of the Northern Ireland Assembly. It follows that, as per an alternative view, the democratic consent mechanism in the Protocol actually adds to the consent role of the Assembly by allowing MLAs to vote on an ‘excepted’ matter outside its existing competences.

- The provision exists in case proceedings have to be suspended for practical reasons, e.g. because of an evacuation owing to fire.

- If the Assembly needs to elect a Presiding Officer for the ‘required sitting day’, this will be its first business of the day. If it fails to elect a Presiding Officer, the oldest MLA presides over the election by a simple majority – as opposed to by a cross-community majority normally – of an ‘interim Presiding Officer’ who holds the position until the alternative democratic consent process has been completed.

- The UK government’s Explanatory Memorandum for SI 2020/1500 makes no reference to ‘opportunity’ and instead states that ‘a further consent decision will be required’ (emphasis added).

- The UK government’s initial proposal was for the provisions to lapse after one year and for arrangements to default ‘to existing rules’.

- The option to amend the Protocol via one or more Decisions of the Joint Committee would not exist. The Joint Committee may only amend the Protocol in specific circumstances and until the end of the fourth year following the end of the transition period, i.e. until 31 December 2024 (see Article 164(5)(d) of the Withdrawal Agreement).

- The 1998 Agreement does not explicitly list the ‘institutions’ that it establishes. Consultation might therefore also include the North-South Implementation Bodies (which already may make proposals to the Specialised Committee on ‘the implementation and application of the Protocol’ (Article 14(b) Protocol) and the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference. The extent of possible consultation would depend on there being a functioning Northern Ireland Executive – necessary also for the operation of the North-South Ministerial Council – and the Northern Ireland Assembly meeting.