Judicial Review and the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland

Billy Melo Araujo and Lisa Claire Whitten

April 2022

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Introduction

The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland entered into force on 31 January 2020 and became operational on 1 January 2021. Since then, there have multiple legal challenges aimed at either the Protocol itself or measures deemed incompatible with it.

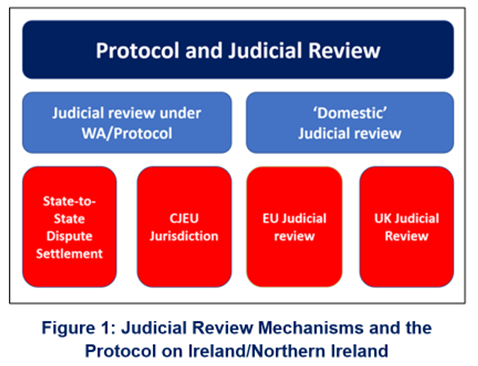

This explainer provides an overview of the judicial review mechanisms that apply in relation to the Protocol. Section 1 explains the architecture of the Protocol’s judicial review system. Section 2 outlines the judicial review mechanisms available under the Withdrawal Agreement, namely the state-to-state dispute settlement mechanism and the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). Sections 3 and 4 examine the judicial review mechanisms available under UK and EU law respectively and the main legal challenges that have arisen since the entry into force of the Protocol.

1. Judicial Review Mechanisms and the Protocol

Judicial review mechanisms relating to the Protocol can be placed into two broad categories (see Figure 1).

Firstly, judicial review mechanisms are specifically provided for in the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement (WA). They can be subdivided into two separate categories. There is the state-to-state dispute settlement mechanism whereby a party can initiate arbitral proceedings against another party for any violation of the WA. Arbitral proceedings can thus be initiated against violations of obligations derived from the Protocol. The Protocol also provides that EU judicial review mechanisms apply in relation to violations of EU law referred to under Articles 5 and 7-10 of the Protocol.

Secondly, the Protocol is also subject to judicial review mechanisms available under both UK and EU law. For example, in recent times, UK courts have ruled on cases disputing the legality of the Protocol under UK law as well as the legality of actions of public authorities in light of the Protocol and those EU laws it makes applicable.

2. Judicial Review under Withdrawal Agreement

2.1 Arbitration Mechanism

Any dispute between the EU and the UK relating to the WA may be brought before an arbitration mechanism created under the WA. The parties must first seek to resolve a dispute amicably via the Joint Committee ‘by entering into consultations in good faith, with the aim of reaching a mutually agreed solution’ (Article 168 WA). Where no amicable solution is found, disputes may be referred to an arbitration panel which must deliver a ruling within twelve months of its establishment (Article 173 WA). A party that wishes the matter to be resolved with urgency – a likely scenario in the case of safeguards disputes – may make such a request to the panel. If the panel accedes to request it will make every effort to issue a ruling within six months (Article 173 WA).

Once delivered, the panel’s ruling will be binding on both parties who must ‘take any measures necessary to comply in good faith with the arbitration panel ruling’ (Article 175 WA). Where the respondent has not complied with the ruling within a reasonable period of time, the complainant can request the panel impose temporary remedies which will take the form of either a lump-sum or penalty payment (Article 178 WA). If payment is not made by the non-complying party within a one-month deadline following the determination of the remedy, the other party may temporarily suspend any part of the WA, except the citizens’ rights provisions, or any other agreement between the EU and the UK (Article 178(2) WA). Any suspension should, however, be proportionate to the breach of the obligation concerned and only apply so long as the breach of the WA persists (Article 178(2) WA).

2.2 CJEU Jurisdiction

The Protocol provides that the CJEU has full jurisdiction for matters pertaining to the application of the following areas of EU law applying to Northern Ireland under the Protocol:

- Customs and movement of goods (Article 5)

- Technical regulations (Article 7)

- VAT and excise (Article 8)

- The single electricity market (Article 9)

- EU State aid rules (Article 10).

This jurisdictional power means that the UK is subject to EU judicial review mechanisms in relation to these areas of EU law.

This includes EU infringement proceedings, a judicial procedure whereby the European Commission can challenge the legality of UK measures violating EU law under the Protocol (Article 258 TFEU[1]). Infringement proceedings are divided into two separate stages: a pre-judicial stage; and a judicial stage.

The pre-judicial stage is intended to give the UK an opportunity to comply with EU law of its own accord. The European Commission must send a letter of formal notice identifying the alleged EU law violation and specifying a period of time within which the UK must respond to the violation. If, following negotiations, the European Commission remains unconvinced that the UK is acting in compliance with EU law it can issue a reasoned opinion which will spell out in detail the nature of the alleged infringement and the deadline for the UK to ensure compliance. The European Commission may also include in the reasoned opinion an outline of the type of measures that the UK could adopt in order to ensure compliance with EU law.

If the UK has not ensured compliance within the time period stated in the reasoned opinion, the European Commission has the discretion to decide whether to initiate the judicial stage of infringement proceedings. If it chooses, the European Commission can bring the case before the CJEU, which will issue a declaratory judgment, holding whether the UK has failed to fulfil its obligations under EU law. Where the CJEU has ruled that the UK has failed to fulfil its obligations, the UK is required to rectify the non-compliance. If, however, the European Commission considers that the UK has not satisfactorily ensured compliance, it can initiate a second judicial procedure before the CJEU which could lead to the imposition of financial sanctions on the UK.

Article 12(5) of the Protocol provides that EU law applicable under the Protocol must produce in the UK the same legal effects as those in the EU and its member states. This means, inter alia, that EU law produces direct effect in the UK. Natural and legal persons in the UK can invoke their rights derived from EU law directly before UK courts and tribunals. In practice, this means that if the UK violates an EU law obligation covered under Article 12(4) of the Protocol (covering Articles 5, 7-10 and 12(2) of the Protocol), the infringement can under certain conditions be challenged directly before a UK court. If a dispute brought before a UK court or tribunal raises a question concerning the interpretation of EU law applicable under the Protocol, the UK court or tribunal would be obliged to make a ‘preliminary reference’ to the CJEU seeking its opinion on the relevant question.

It is worth noting that not all provisions of EU law produce direct effect. For a provision of EU law to have direct effect it must meet the conditions of being clear, precise, and unconditional. Where this is not the case, however, other features of EU law come into play such as the principle of indirect effect (national courts must, where possible, interpret national law in line with EU law) and state liability (the UK is obliged to compensate individuals for damages suffered as a result of breaches of EU law).

2.3 The Dispute over Grace Periods

On 17 December 2020, the UK and the EU issued unilateral declarations allowing the former not to apply certification checks on food products imported from Great Britain into Northern Ireland during a maximum time period of three months after the end of the transition period. On 31 of December 2021 the EU and the UK also confirmed that, for the same time-period, no customs checks would apply for online retailers sending parcels from GB into NI. In other words, the UK was granted ‘grace periods’ during which it would not have to apply certain EU customs and regulatory compliance checks required under the Protocol. The declaration further provided that during the grace period, the UK would take all necessary measures to ensure compliance with the Protocol and relevant EU law as of 1 April 2021.

However, on 3 March 2021, the UK government announced that it would unilaterally extend grace periods applicable to agri-foods and online retail parcels moving from Great Britain into Northern Ireland. The EU claimed that the UK’s decision was in breach of two obligations under the WA. Firstly, it violated Article 5(3) and (4) Protocol (read in conjunction with relevant EU law listed in Annex 2 of the Protocol) which require the UK to comply with EU customs and internal market rules on trade in goods. Secondly, the EU claimed that by unilaterally extending the grace periods without engaging in a prior consultation with the EU, the UK had violated Article 5 WA which establishes a duty of good faith on the Parties.

With respect to the first alleged violation, the European Commission opted to initiate infringement proceedings against the UK. This was possible because under Article 12(4) of the Protocol, violations of EU law obligations covered by Article 5 of the Protocol are subject to the jurisdiction of the CJEU. On 15 March 2021, the European Commission sent a letter of formal notice to the UK where it: (i) requested the UK carry out remedial actions to ensure compliance with the relevant EU law obligations under Protocol; and (ii) gave the UK one month to respond to the allegations. With respect to the alleged violation of the good faith requirement, the EU sent a letter to the UK formulating its intention to trigger bilateral consultations in the framework of the Joint Committee, a prerequisite for the initiation of arbitral proceedings.

On 21 July 2021, the UK published a Command Paper entitled Northern Ireland Protocol: the way forward where it called on the EU to ‘freeze existing legal actions and processes, to ensure there is room to negotiate without further cliff edges, and to provide a genuine signal of good intent to find ways forward’. On 27 July 2021, the EU responded by suspending both legal challenges against the UK’s unilateral extension of grace periods. Both parties have since been discussing potential solutions to address the trade issues that led to the dispute. The parties have also agreed to keep the grace periods in place while these discussions are ongoing. The European Commission, however, made it clear that it had not completely abandoned the infringement proceedings. It stated that it had decided not to move to the next stage of the proceedings “at present” but that it reserved its rights in respect of these proceedings, In other words, the European Commission paused the legal challenges in order to explore practical solutions to address issues associated with the implementation of the Protocol but did not exclude the possibility of relaunching them in the future should the parties fail to secure a solution and the implementation issues persist.

3. Judicial Review under UK Law

3.1 UK Law Context: General Implementation

To account for the relevant procedures available for judicial review under UK law, it is helpful to first sketch out the domestic law provisions for the implementation of the WA and Protocol.

Under the UK’s dualist legal system, to give domestic legal effect to the WA – an international treaty – Parliament was required to pass legislation to that end. This was achieved by the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 (EUWAA 2020) which received royal assent on 23 January 2020 and enabled the UK to formally withdraw from the EU eight days later. The EUWAA 2020 amended an earlier piece of legislation, the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (EUWA 2018). As amended, the EUWA 2018 gives legal force to the WA in its entirety (section 7A) and grants specific powers to UK Ministers to make further arrangements, as necessary, for the implementation of the Protocol by secondary legislation (section 8C).

Under the heading ‘General implementation of remainder of withdrawal agreement’ section 7A(1) of the EUWA 2018 provides that:

- all such rights, powers, liabilities, obligations, and restrictions from time to time created or arising by or under the withdrawal agreement, and

- all such remedies and procedures from time to time provided for by or under the withdrawal agreement, as in accordance with the withdrawal agreement are without further enactment to be given legal effect or used in the United Kingdom.[2]

The language of section 7A is strikingly comprehensive; its drafting mirrors that of section 2(1) of the European Communities Act 1972 (ECA 1972) which, previously, served as a ‘conduit pipe’[3] by which EU law had supremacy and direct effect in the UK. What this means is that, just as section 2(1) of the ECA 1972 gave EU law direct effect in the UK when it was a member state, so section 7A of the EUWA 2018 gives the WA – Protocol included – direct effect in the UK post-Brexit.

The language of section 8C of the EUWA 2018 is also broad in scope and the powers it gives UK ministers to implement the Protocol through secondary legislation are sweeping. Under the heading ‘Power in connection with Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol in withdrawal agreement’ ministers are granted discretionary powers to use regulations to: (a) implement the Protocol; (b) supplement the effect of section 7A in relation to the Protocol; and (c) otherwise deal with matters arising out of, or in relation to, the Protocol. In relation to judicial review, the nature of these section 8C powers are notable because secondary legislation is generally subject to judicial review proceedings in the UK system.

The legal significance of the comprehensive provision in section 7A and the sweeping powers granted Ministers in section 8C of the EUWA 2018 can only be fully understood when read in light of, in particular, Article 4 of the WA, as well as Articles 12(4) and 13(2) of the Protocol.

The former states:

- The provisions of this Agreement and the provisions of Union law made applicable by this Agreement shall produce in respect of and in the United Kingdom the same legal effects as those which they produce within the Union and its Member States…

- The United Kingdom shall ensure … its judicial and administrative authorities [have powers] to disapply inconsistent or incompatible domestic provisions…

- The provisions of this Agreement referring to Union law or to concepts or provisions thereof shall be interpreted and applied in accordance with the methods and general principles of Union law…

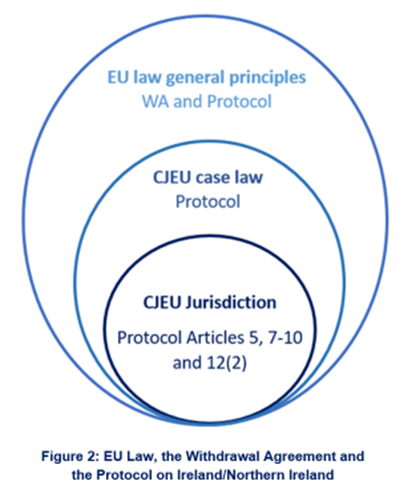

Thus, Article 4 of the WA explicitly provides for the continuation of the principles of direct effect, supremacy, and general principles of EU law in relation to the WA in its entirety, including the Protocol and those EU instruments that fall within its scope; Article 4 of the WA does not, however, make provision for continued CJEU jurisdiction. By contrast, Article 12(4) of the Protocol does provide that full CJEU jurisdiction is retained but (only) as regards the implementation of Article 5 and Articles 7-10 of the Protocol with Article 267 of the TFEU applying to the UK for this purpose. Alongside this, Article 13(2) of the Protocol provides that ‘the provisions of this Protocol referring to Union law or concepts or provisions thereof shall in their implementation and application be interpreted in conformity with the relevant case law’ of the CJEU. There are, therefore, three levels to the ongoing relationship between EU law proceedings and different aspects of the WA, including the Protocol, set up under its terms (see Figure 2).

By giving the WA and Protocol direct effect in the UK post-Brexit, the ‘conduit pipe’ provision of section 7A of the EUWA 2018 also, in effect, introduces different mechanisms for enforcement depending on which Article is in question and, therefore, the relevance of EU law mechanisms vis-à-vis UK law mechanisms for redress. This differentiation has implications for the operation of judicial review relating to the Protocol: while decisions made under any of the Articles of the Protocol (or WA) are subject to UK judicial review, only those Articles of the Protocol covered by full CJEU jurisdiction are also subject to EU judicial review.

If questions regarding the interpretation or application of EU laws were to arise in UK judicial review cases concerning those Articles of the Protocol that are not covered by CJEU jurisdiction (i.e. Articles 1-4, 6, 11, 13-19) the UK Courts are still likely to seek an opinion from the CJEU given the overarching provisions in Article 4 of the WA and also the requirement for continued alignment with CJEU case law, under Article 13(2) of the Protocol, in the application of these Articles.

3.2 UK Law Judicial Review Procedure

Following the ‘catch-all’ implementation of the Protocol in domestic UK law (via section 7A EUWA 2018), the provisions of the Protocol are subject to UK judicial review mechanisms according to established practice. This means, in short, that individuals and legal persons can challenge the lawfulness of the state’s decision to implement the Protocol or challenge the lawfulness of state decisions in light of that implementation; both such scenarios have already arisen in UK case law.[4]

In the UK setting, judicial review cases are concerned with the lawfulness or otherwise of the process by which a decision of the state has been taken, rather that the decision itself. To be subject to challenge by judicial review, the relevant decision must have been: (i) made by a public body; (ii) made using secondary legislation; (iii) deemed to give rise to a case; and (iv) brought by a natural or legal person with the right to do so based on a ‘sufficient/public interest’ test. Additionally, applications for judicial review in the UK must normally be brought within three months of the relevant decision being taken. However, Northern Ireland Courts can decide to hear challenges outside this timeframe if there is ‘good reason’ for doing so.[5]

This latter requirement relates to the issue of ‘standing’. The question of whether or not an applicant has standing (or locus standi) to bring a judicial review challenge is often determined by the Court alongside the merits of the case. The key criterion for deciding standing is whether or not applicants have a ‘sufficient interest’ in the matter to which the application relates; alternatively, Courts can hear applications on the grounds that it is in the ‘public interest’ to do so. Specific provisions regarding standing to bring judicial review cases regarding Article 2 of the Protocol also exist. Under section 23 and Schedule 3 of the EUWAA 2020, the Northern Ireland Act 1998 was amended so as to enable the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland and the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission to bring, or intervene in, judicial review cases with respect to an alleged breach or potential future breach of Article 2 of the Protocol regarding individual rights.[6]

There are three grounds on which judicial review cases can be heard: illegality (did the decision-maker have the necessary authority?); irrationality (was the decision reasonable?) and procedural impropriety (was the correct procedure followed?). If the ruling is in favour of the claimant on any one of these three grounds, the Court can: overturn the original decision (quashing order); compel the decision-maker to take a certain action (mandatory order); prevent the decision-maker from taking a certain action that would later be quashed (prohibiting order); or issue an injunction (this can be either mandatory or prohibitive and can be temporary) or a declaration.

The criteria by which UK courts determine whether judicial review applications relating to the Protocol ought to be heard and judged (on grounds of illegality, irrationality, or procedural impropriety) will need to account for the varied relationships between different Articles of the Protocol and the extent of relevance of EU law principles or procedures.

3.3 UK Judicial Review Case: re Allister and Others

A cross-party group of unionist politicians and individuals applied for judicial review of the decision of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to make regulations, under section 8C of the EUWA 2018, to implement the Protocol in UK law. The high profile of the appellants in this case, as well as its implicit challenge to the implementation of the Protocol on the grounds of UK constitutional law principles, make this a particularly important case to consider.

The application for judicial review was first heard in the Northern Ireland High Court and then in the Northern Ireland Court of Appeal; in both instances the appellants’ arguments were rejected on all grounds and the case(s) were dismissed.[7]

Formally, the focus of the application was on The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland (Democratic Consent Process) (EU) Regulations 2020 (the ‘2020 Regulations’) which implement Article 18 of the Protocol by establishing a process by which the Northern Ireland Assembly will be given the opportunity to vote for or against the continuation of Articles 5 and 7-10 of the Protocol. The Northern Ireland Courts recognized that the challenge was in effect to the Protocol itself and provision for its overall implementation in UK law via EUWA 2018 as amended by EUWAA 2020. In deciding to hear the case, the Northern Ireland Courts deemed it in the ‘public interest’ that the issues of the case be considered and determined by the highest court in Northern Ireland and permitted an extension of the normal requirement for challenges to be brought within three months of the relevant decision.[8]

The appellants in the case of Allister and Others challenged the legality of the UK government decision to implement the Protocol via the 2020 Regulations on five grounds that:

- the Protocol and the 2020 Regulations were incompatible with Article VI of the Act of Union 1800 for ‘subjects of Great Britain and [Northern] Ireland shall be on the same footing in respect of trade…’

- the Protocol and the 2020 Regulations were incompatible with the provision in section 1(1) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 regarding the constitutional status of Northern Ireland and the principle of consent to its change.

- the UK government acted unlawfully by not making the Protocol’s ‘democratic consent process’ subject to section 42 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, the ‘constitutional safeguard’ requirement for cross-community consent in the Northern Ireland

- by enabling EU laws to apply in Northern Ireland without the electorate being able to influence or input to the formation of those laws, the implementation of the Protocol violates Article 3 of Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and Article 14 of the same.

- the Protocol is invalid due to conflict with Articles 10 and 50 of the Treaty of the European Union (TEU).

Focusing on the ruling of the High Court in relation to the first matter, the Court of Appeal concluded that Article VI of the Acts of Union 1800 had been ‘modified’ by section 7A of the EUWA 2018 and must therefore be read as ‘subject to’ it and, in effect, the Protocol, but that there was no incompatibility between the two legislative provisions.[9] On the second question regarding the constitutional status of Northern Ireland and the principle of consent, the Court found there to be no conflict with section 1(1) of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, stating that ‘the constitutional status of NI within the United Kingdom has not changed and cannot change other than by virtue of the mechanism provided’ therein.[10] On the third issue, the section 42 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998 requirement for cross-community consent on certain issues was deemed irrelevant to the 2020 Regulations because they concern international relations and are therefore outside the competence of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the Northern Ireland Executive.[11] On the final two grounds, the Court found there to be no breach of the relevant Articles in either the ECHR or the TEU.[12]

The appellants in Allister and Others sought leave for their challenge to be heard in the UK Supreme Court (UKSC). In April 2022, the Court of Appeal in Belfast referred the case to the UKSC for consideration of the first three issues raised: (1) compatibility with the Act of Union; (2) compatibility with provisions regarding constitutional status of Northern Ireland; and (3) disapplication of requirement for cross-community consent. Any UKSC judgment is unlikely until 2023.

4. Judicial Review under EU Law

4.1 EU Judicial review

The Protocol, as part of an international agreement entered into by the EU, forms an integral part of the EU legal order. The validity of the Protocol can therefore be reviewed in light of the provisions of EU treaties. It also means that EU acts can be set aside if they violate provisions of the Protocol.

Some of the options available for judicial review under EU law have already been outlined above in section 3. International agreements concluded by the EU can have direct effect to the extent that such effect is not excluded in said agreement and as long as certain conditions are met, namely that the provision in question should establish obligations that are unconditional and sufficiently precise. In that case, persons can invoke their rights derived from the Protocol directly before courts or tribunals of member states.

If, for example, customs authorities in Ireland were to decide to impose barriers on goods moved from Northern Ireland into Ireland, private persons could challenge such measures by reference to the provisions of the Protocol (for example, under the Article 5(5) and the prohibition of quantitative restrictions on imports and exports between Northern Ireland and EU member states) directly before Irish courts.

Further, if a question relating to the interpretation or the validity of the interpretation of EU law arises during a domestic proceedings, national courts or tribunals can refer a preliminary question to the CJEU. The domestic proceedings are suspended until the CJEU delivers its ruling. Such rulings will bind the referring domestic court insofar as it is required to apply EU law in the manner in which it has been interpreted by the CJEU.

There are other mechanisms through which the legality of acts under the Protocol can be challenged directly before the EU courts. As previously noted, the failure by a member state to comply with obligations under the Protocol can be challenged by the European Commission through infringement proceedings. Member states can also initiate infringement proceedings against one another in the context of a slightly abridged procedure (Article 259 TFEU).

With respect to direct challenges against EU institutions, there are three important avenues of review available. Firstly, there is an action for annulment which is directed at EU acts (Article 263 TFEU). Secondly, there is an action for failure to act which targets the inaction of EU institutions (Article 265 TFEU). And, thirdly, there is an action of damages against the EU which is intended to provide applicants with a route to obtain damages from the EU (Article 340 TFEU).

An annulment action is a judicial mechanism that allows interested parties to bring a direct action against and challenge the legality of EU acts. Under this procedure, EU measures can be reviewed on the grounds of: lack of competence (e.g. an EU institution uses an incorrect legal basis for act); infringement of procedural requirements (e.g. failure to explain the rationale of the action taken); or infringement of an EU Treaty or any rule relating to its application (Article 263(2) TFEU). The last ground for review includes breach of binding international agreements entered into by the EU.[13] This would, of course, include the provisions of the Protocol.

However, there are several conditions that must be met by interested parties wishing to bring an action for annulment before the CJEU. First, any claim must be made within two months from the date of the publication of the measure being challenged, its notification to the plaintiff, or of the day on which it came to the knowledge of the latter (Article 263(6) TFEU). Second, only EU acts that produce binding legal effects can be subject to review (Article 263(1) TFEU).

Annulment actions may be lodged by EU institutions, EU member states, some EU bodies and natural or legal persons. The European Parliament, the Council, the European Commission and EU Member States (Article 263(2) TFEU) – so-called ‘privileged applicants’ – may bring an action for annulment directly before the CJEU without establishing that they have an interest, since they are assumed to have an interest in ensuring compliance with EU law (Article 268 TFEU).

Annulment actions filed by natural or legal persons (Article 263(4) TFEU) – so-called ‘non-privileged applicants’ – are more problematic because of restrictive standing requirements.[14] Indeed, for such applicants, the most significant barrier to review is the standing requirement. Unless applicants are addressed in the safeguard measure, they would have to show that they are either (i) directly concerned by a regulatory act not entailing implementing measures; or (ii) both directly and individually concerned by the safeguard measure (Article 264(4) TFEU). The condition of ‘individual concern’ is particularly problematic in that it requires a demonstration that the act affects the applicants by reason of certain attributes that are peculiar to them or by reason of circumstances in which they are differentiated from all other persons. The individual concern requirement has been interpreted and applied so restrictively under EU case law that it is nigh on impossible for non-privileged applicants to satisfy the standing requirements.[15]

The action for failure to act complements the action for annulment by providing applicants with the right to challenge the failure by an EU institution to act where there is a legally binding obligation to do so. Like annulment proceedings, non-privileged applicants have a limited standing insofar as an action can only be initiated where it can be shown that an EU body was required to address an act specifically to them. A further complication with this procedure is that, in practice, demonstrating that an EU institution is bound by a sufficiently clear and precise obligation to act is not always straightforward.[16]

Finally, EU institutions can be held liable for any damages caused by an unlawful act they have committed (Article 340 TFEU). Any party that has suffered damages as a consequence of a violation of EU law by an EU institution can initiate an action for damages before the CJEU. However, liability can only be triggered if the applicant is able to demonstrate a sufficiently serious breach of an act of EU law intended to confer rights. This is the case where an EU institution has ‘manifestly and gravely disregarded the limits on its discretion’[17]. In other words, the greater the discretion given to EU institutions, the harder it is to establish liability.

4.2 McCord v Commission[18]

In McCord v Commission, a private applicant sought to challenge the European Commission’s short-lived proposal to apply export restrictions on COVID-19 vaccines in NI. It is to date the only legal challenge, brought directly before the CJEU, against a measure adopted by an EU institution in light of the Protocol.

On 29 January 2021, the European Commission published a draft regulation proposing the application of export restrictions on COVID-19 vaccines. The draft regulation provided for the imposition of such export restrictions on vaccines exported to Northern Ireland. Such restrictions were clearly incompatible with obligations under the Protocol. For this reason, the draft regulation argued that the restrictions were justified by reference to Article 16 of the Protocol, which allows the parties to derogate from obligations where they can show that application of the Protocol has led to serious economic, societal, or environmental difficulties that are liable to persist’. More specifically, the draft regulation argued that the COVID-19 pandemic combined with a shortage of vaccines amounted to an instance of serious societal difficulty.

The possibility that restrictions would be applied by the EU on trade within the island of Ireland caused was met with significant political resistance. The European Commission immediately responded by dismissing the proposed use of an Article 16 safeguard and instead proceeded with Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/111 which contained no references to Northern Ireland or the Protocol.

On 8 February 2021, Mr. Raymond Irvine McCord, informed the European Commission of his concerns regarding the draft regulation and the possible triggering of Article 16 of the Protocol. The letter requested that the European Commission publicly acknowledge that its ‘decision to trigger [Article 16] was unlawful’ and to formulate ‘a policy on the triggering of [Article] 16’. The European Commission responded that the draft regulation was a working draft that was never formally adopted. Mr. McCord considered that this response did not fully address his concerns and, on 25 March 2021, lodged two actions against the European Commission. The first was an annulment action, through which the applicant asked the General Court to quash: (i) the draft regulation; and (ii) the decision not to publish a formal policy on Article 16 Protocol. The second action was for a failure to act requesting the General Court to declare that the European Commission acted unlawfully by failing to publish a policy on Article 16 and to order the European Commission to adopt and publish such policy.

The General Court of the CJEU ruled that the annulment action was inadmissible on all counts.[19] Firstly, it ruled that the action was manifestly inadmissible in relation to the draft regulation insofar as it constituted an act which does not have legal effects that are binding on, and capable of affecting the legitimate interests of, the applicant. Secondly, the General Court ruled that the annulment action in relation to the Commission’s decision not to publish its policy on Article 16 of the Protocol was also inadmissible insofar as it targeted a non-existent act.

The action for failure to act was also deemed inadmissible as, in line with established CJEU case law, such legal challenges are only permitted where an EU institution has failed to act despite the existence of an obligation to act. In this particular case, the General Court noted the decision whether to release of policy on Article 16 of the Protocol fell under the discretionary power of the European Commission. The request to order the European Commission to publish a policy was also deemed inadmissible, as EU courts do not have the power to issue directions to EU institutions.

Conclusion

The provisions of the Protocol are novel in both the UK and the EU legal contexts; so too are the arrangements for their implementation and enforcement. As this explainer has set out, there are a range of different mechanisms available for the Protocol’s enforcement; and the applicability, or otherwise, of each will depend not only on the specific facts of a given case, but also on which Article of the Protocol is in question and, therefore, the extent to which EU law mechanisms as opposed to UK law mechanisms are relevant for the purposes of redress. In view of the novelty of the Protocol’s provisions, and the consequential complexity of mechanisms available for their enforcement, the development of case law associated with the Protocol’s implementation is likely to be particularly significant in determining its impact.

Furthermore, in concluding, it is worth noting the degree of contingency that currently exists as regards the implementation of the Protocol given that talks between the UK and the EU on the matter are still ongoing.

April 2022

Notes

- Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- Inserted by section 5 of the EUWAA 2020

- As described by the UK Supreme Court in Miller vs Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, 2017 UKSC 5.

- An example of a challenge to the lawfulness of state’s decision to implement the Protocol – the case of Allister and Others ([2022] NICA 15) – is discussed below. For an example of a challenge to the lawfulness of the state decisions in light of implementation, see the case of British Sugar Plc, R (On the Application Of) v Secretary of State for International Trade ([2022] EWHC 393) which concerned, among other things, the lawfulness of measures adopted by the UK government under the post-Brexit UK General Tariff regime in light of Article 10 of the Protocol.

- Rules of the Court of Judicature (Northern Ireland) 1980, Order 53, rule 4.

- Section 78C of the Northern Ireland Act 1998.

- The case involves two separate applications. The first was brought by a group of unionist politicians including Jim Allister, leader of the Traditional Unionist Voice party, the then leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, Arlene Foster, the then leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, Steve Aiken, Baroness Kate Hoey of the Labour Party, and Ben Habib of the Brexit Party (the ‘Allister case’). The second application was brought by an individual unionist, Clifford Peeples (the ‘Peeples case’). Given the ‘substantial degree of overlap between the two applications’ the High Court determined to hear the two together while adopting the Allister case as the lead ([2021] NIQB 64: 37-43); the two cases remained cojoined in the Court of Appeal.

- Allister and Others [57].

- Allister and Others [298] (iv).

- Allister and Others [298] (v).

- Allister and Others [298] (vi).

- Allister and Others [298] (vii)(viii).

- Turk, A.H. Judicial Review in EU law (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2009).

- Rhimes, M. ‘The EU Courts Stand Their Ground: Why are Standing Rules for Direct Actions so restrictive?’ European Journal of Legal Studies, 9 (1) 2016, 103-72.

- Roer-Eide, H. and Eliantonio, M. ‘The Meaning of Regulatory Act Explained: Are There Any Significant Improvements for the Standing of Non-Privileged Applicants in Annulment Actions?’ (2013) German Law Journal 14 (9) 2013, 1851-65.

- Case T-395/04 Air One ECLI:EU:T:2006:123

- Case 5-71 Aktien-Zuckerfabrik Schöppenstedt v Council of the European Communities [1971] ECR I-00975.

- T-161/21, McCord v Commission, 14 December 2021.

- Cases T‑161/21 and T‑161/21, McCord v Commission 14 December 2021, ECLI:EU:T:2021:910.