Dynamic Regulatory Alignment and the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland - Eighteen Months

Lisa Claire Whitten

July 2022

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Introduction

Northern Ireland occupies a unique position in the relationship between the United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union (EU). The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland provides that aspects of EU law continue to apply in Northern Ireland despite it having left the EU along with the rest of the UK on 31 January 2020.

Under the terms of the Protocol, Northern Ireland remains part of the UK customs territory. However, the EU customs code continues to apply in respect of Northern Ireland as do specific EU acts that regulate the free movement of goods, VAT and excise, state aid and electricity markets. New EU acts that fall within the scope of the Protocol may also be added to those that apply in Northern Ireland.

Moreover, the Protocol requires that amendments or replacements to these acts apply in Northern Ireland. Such dynamic regulatory alignment is necessary to maintain the free movement of goods on the island of Ireland. However, this has proved politically controversial, not least because it involves EU acts applying in Northern Ireland in which neither the UK nor Northern Ireland has had a direct role in adopting.

The UK government recently proposed domestic legislation – the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill (NIP Bill) – that would, if enacted, disapply those provisions of the Protocol in UK law that currently provide for the continued application of EU law in Northern Ireland. As the NIP Bill is still going through the parliamentary process the arrangements for Northern Ireland agreed to by the UK and the EU in the text of the Protocol still apply.

Focusing on the existing legal situation, this explainer reviews the substance of the first eighteen months of ‘dynamic regulatory alignment’ with those elements of EU law applicable in post-Brexit Northern Ireland. The content builds on two previous reviews carried out after the first six months and first twelve months of ‘dynamic regulatory alignment’ with the EU under the Protocol.

The extent of change after eighteen months does not differ much from that presented after one year of the Protocol’s implementation; this is itself an important finding. The absence of significant change in the first half of 2022 reflects the slow pace of the EU legislative process and the relative stability of the specific set of EU acts that continue to apply in the UK in respect of Northern Ireland.

This notwithstanding, regular minor changes and technical updates to EU implementing legislation also apply to Northern Ireland. While many of these changes have little or no impact in Northern Ireland in terms of policy, some do have implications for certain industries and stakeholders, a fact which underlines the ongoing importance of monitoring the legal and practical impacts of the unique position of Northern Ireland.

Given the slow pace of change, the policy impacts of dynamic regulatory alignment for Northern Ireland under the Protocol are not as extensive as they could be. This is not to say dynamic regulatory alignment does not raise challenges in respect of practical impacts for industry, democratic accountability, and capacity for legislative scrutiny. Following a review of the first eighteen months of implementation, the conclusion to this explainer returns to these challenges.

1. The new dynamism of Northern Ireland

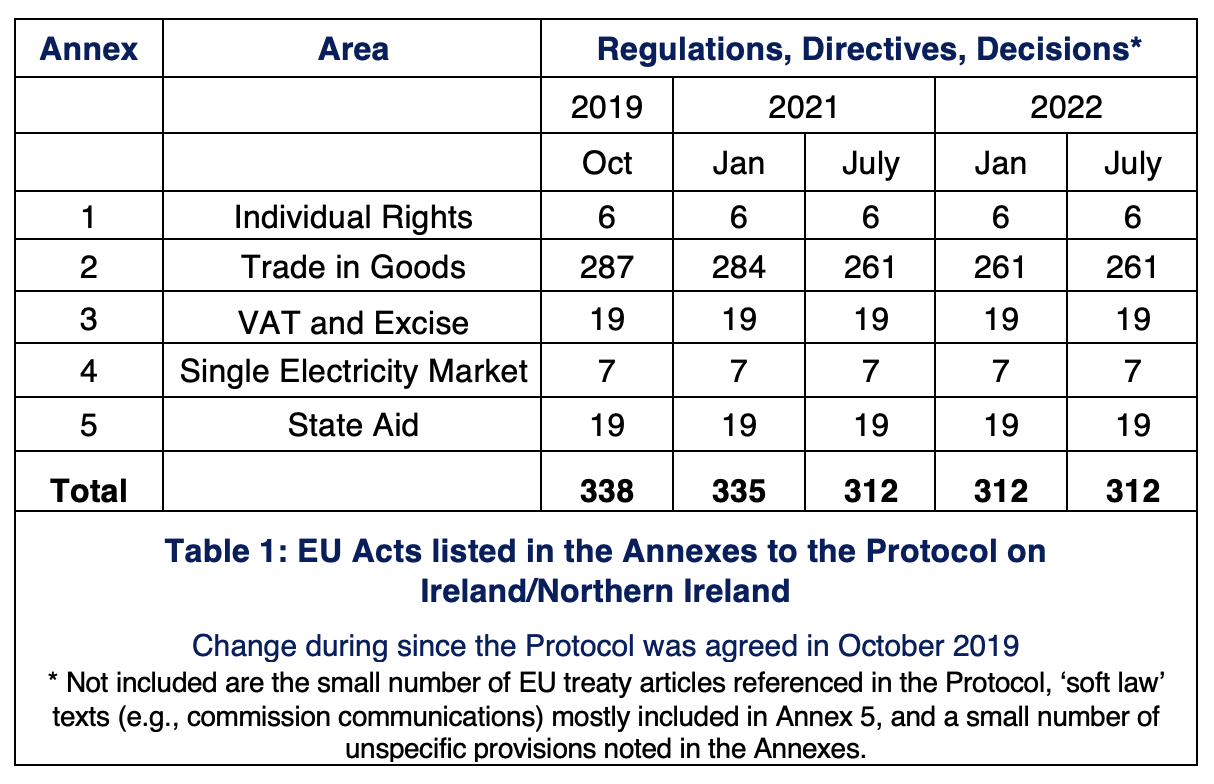

Under Article 13(3) of the Protocol, EU acts listed in Annexes to the Protocol apply ‘as amended or replaced’ to the UK in respect of Northern Ireland. When the Protocol and its Annexes were agreed by UK and EU negotiators as part of the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement in October 2019, 338 acts were listed. Under the Protocol, additions can be made, and acts can also be deleted.

This means that, under the Protocol, Northern Ireland is in a position of ‘dynamic alignment’ with a specified but potentially evolving selection of the EU ‘acquis’, the body of legal and other agreed obligations and commitments that apply to, and in, EU member states.

In implementing the Protocol, therefore, the UK must keep Northern Ireland aligned with any changes made to the EU acts included in the scope of the Protocol.

Eighteen months after the Protocol entered into force, how has the body of EU law that applies to, and in, Northern Ireland changed?

Like many issues in the world of Brexit, the answer is not simple. Several different types of change have taken place. They fall into three broad categories:

- additions to and deletions from the Annexes to the Protocol;

- repeal, replacement, and expiry of applicable EU law; and

- changes to EU legislation that implements applicable EU law.

2. Additions to and deletions from the Annexes to the Protocol

The first category of change concerns the specific EU acts that apply in Northern Ireland under the Protocol. Through the Joint Committee set up to oversee the implementation of the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, the UK and the EU can, by agreement, add new EU acts that fall within the scope of the Protocol to the relevant Annexes (Article 13(4) Protocol). The Joint Committee can also remove acts listed.

Before the end of the transition period, in December 2020, the UK and EU agreed to add eight EU acts to Annex 2 of the Protocol. It also agreed to remove two EU acts listed in the same Annex.

Of the eight acts added, five related to legislation that the Joint Committee decided, following review, should have been included in the original text of Annex 2. The five acts that were added are:

- rules for monitoring trade between the EU and third countries in drug precursors (Council Regulation (EC) 111/2005);

- use of indications or marks to identify the lot – or batch – to which food products belong (Directive 2011/401/EU);

- rules on the marketing of fodder plant seed (Council Directive 66/401/EEC);

- rules on the marketing of propagating material of ornamental plants (Council Directive 98/56/EC); and

- rules on the marketing of vegetable propagating and planting material other than seed (Council Directive 2008/72/EC).

The three other additions were new EU acts adopted since the content of the Protocol had initially been agreed in November 2018. The Joint Committee decided that the following three acts fell within the scope of the Protocol, so added these to Annex 2:

- bilateral safeguard clauses and other mechanisms for the temporary withdrawal of preferences in certain EU trade agreements with third countries (Regulation (EU) 2019/287);

- measures to reduce the impact of certain plastic products on the environment (Directive (EU) 2019/904); and

- and measures to control the introduction and import of cultural goods (Regulation (EU) 2019/880).

The two acts that were removed by the Joint Committee concerned CO2 emissions standards for passenger cars (Regulation (EC) 443/2009) and light-duty commercial vehicles (Regulation (EU) 510/2011). Their original inclusion was deemed unnecessary.

Taking just these changes into account, when the Protocol entered into force on 1 January 2021 following the end of the transition period, 344 EU acts were listed in its Annexes.

Although the Joint Committee has met on three occasions since then - 14 February 2021, 9 June 2021, and 21 February 2022 – it has not adopted any decision to add or delete any EU acts. The European Commission has nevertheless signalled that certain proposed legislation being considered for the EU may fall, in part at least, within the scope of the Protocol. This includes, for example, the proposed Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) regulation. UK and EU officials have discussed the matter although no definitive position has yet been taken.

3. Repeal, replacement, and expiry of applicable EU Law

The second category of change covers the repeal, replacement, and expiry of EU acts – regulations, directives, and decisions – listed in the Annexes to the Protocol. Changes in this category are the result of normal EU legislative processes and follow from the provision in Article 13(3) of the Protocol stating that relevant EU acts apply as ‘amended or replaced’ to and in Northern Ireland.

Of the 338 EU acts originally listed in the Annexes, 51 had been repealed as of 1 July 2022. Only two of these had been repealed in the previous six months.

Not all of the EU acts repealed so far have, however, been directly replaced by a new piece of EU legislation. This is because several relevant changes consolidated provisions previously spread over numerous pieces of (now repealed) legislation, into one or two new, more comprehensive, acts.

The 51 repealed acts have been replaced by 19 new acts. Even eighteen months since the Protocol entered into force, in most instances, this dynamic alignment concerns changes to pieces of EU legislation that had been adopted prior to the UK’s withdrawal from the EU on 31 January 2020. Of the 19 replacement acts, only six were adopted after the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020 and three since the end of the UK Transition Period on 1 January 2021.

In terms of coverage, 23 of the 51 repealed acts concerned controls on animal health and were replaced by two new pieces of legislation: Regulation (EU) 2016/429 and Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/687. The former is known as the ‘Animal Health Law’ and the latter is a related, supplementary act. Together these two new acts incorporate, and update pre-existing provisions set out in the 23 repealed acts.

The changes laid down in the Animal Health Law were agreed in March 2016, before the UK’s EU referendum and therefore with the UK taking full part in their adoption. The original text included transitional measures and allowed for the repeal of the earlier acts to take effect in April 2021.

As a supplement to the 2016 Regulation, the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/687 sets out measures to prevent and control the spread of certain diseases. The relevant diseases were listed in the 2016 regulation but required more specific provisions; these are laid down in the later act.

In a similar way, seven of the other repealed acts concerned EU rules on official controls and checks on food and feed, animal health and welfare standards, plant health and plant protection. These were replaced by a single overarching EU act: Regulation (EU) 2017/625, known as the ‘Official Controls Regulation’. It incorporates and updates pre-existing provisions in the repealed acts. It was agreed in April 2017, shortly after the UK triggered Article 50 announcing its intended withdrawal from the EU and so with the UK participating in the regulation’s adoption. The new Regulation ((EU) 2017/625) included transitional measures and allowed for the repeal of the earlier acts to take effect in December 2019.

Also repealed were two directives – Council Directive 93/42/EEC and Council Directive 90/385/EEC – concerning the production of and trade in medical devices. This had been provided for in Regulation (EU) 2017/745 which was already listed in Annex 2 to the Protocol, so the repealed directives were not replaced directly.

In addition, two regulations concerning requirements for the use of statistics on (respectively) trade in goods between EU member states and with non-EU countries – Regulation (EC) No 638/2004 and Regulation (EC) No 471/2009 – were repealed and replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/2152 on European business statistics that incorporates and updates requirements from the earlier acts. The new regulation was agreed in November 2019, when the UK was still an EU member state; it also included transitional measures for the scheduled repeal of earlier acts to take effect at the end of 2021.

A further 17 repealed regulations and directives originally listed in the Protocol have been replaced directly by new acts. Of these replacement acts, four concern the regulation of electricity markets and energy supplies (Directive 2009/72/EC, Regulation (EC) 714/2009, Regulation (EC) 713/2009 and Directive 2005/89/EC) and were originally listed in Annex 4, supplementing Article 9 of the Protocol which makes provision for the continued operation of the Single Electricity Market on the island of Ireland. These four acts were replaced by four updated acts (Directive (EU) 2019/944, Regulation (EU) 2019/943, Regulation (EU) 2019/942 and Regulation (EU) 2019/941 respectively) between July 2019 and December 2020. The replacement acts cover the same policy areas and implement changes agreed in June 2019 – again while the UK was still a member state of the EU.

The 13 remaining acts have been repealed and replaced directly, eleven of these were repealed in the first year of implementation and two in the last six months; they concern:

- the approval and market surveillance of motor vehicles and related products (Directive 2007/46/EC) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2018/858 adopted in June 2018;

- controls on cash entering or leaving the EU (Regulation (EC) 1889/2005) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2018/1672 adopted in November 2018;

- controls on trade in goods that could be used in capital punishment or torture (Council Regulation (EC) 1236/2005) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/125 adopted in January 2019;

- the mutual recognition of goods between member states (Regulation (EC) 764/2008) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/515 adopted in March 2019;

- controls on persistent organic pollutants (Regulation (EC)8 50/2004) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 adopted in June 2019;

- the marketing and use of explosives precursors (Regulation (EU) 98/2013) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1148 adopted in July 2019;

- provisions for the conservation of fisheries and marine ecosystems (Council Regulation (EC) 850/98)replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1241 adopted in July 2019;

- provisions for computerising the movement and surveillance of exercisable goods (Decision 1152/2003/EC) replaced by Decision (EU) 2020/263 adopted in February 2020;

- rules on the labelling of tyres (Regulation (EC) 1222/2009) replaced by Regulation 2020/740 adopted in June 2020; and

- controls on the acquisition and possession of weapons (Council Directive 91/447/EEC) replaced by Directive (EU) 2021/555 adopted in April 2021; and

- the EU regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items (Regulation (EC) 428/2009) repealed by Regulation (EU) 2021/821 adopted in May 2021 but with provision for the continued application of authorisations made under the earlier act and before 9 September 2021.

Those repealed and replaced in the first six months of 2022 are:

- the EU code relating to veterinary medicinal products (Directive 2001/82/EC) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/6 adopted in December 2018;

- conditions governing the preparation, placing on the market and use of medicated feeding stuffs in the EU (Directive 90/167/EEC) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/4 adopted in December 2018.

In addition to the 51 repealed acts, two acts originally listed in the Annexes expired after the UK withdrew from the EU. These concerned the regulation of imports from third countries affected by the Chernobyl disaster (Council Regulation (EC) 733/2008) and temporary trade measures for goods originating in Ukraine (Regulation (EU) 2017/1566).

Considering all these changes alongside those agreed by the Joint Committee in December 2020, the number of EU acts that apply in post-Brexit Northern Ireland has decreased since the Protocol entered into force. As of 1 July 2022, there are now 312 EU regulations, directives and decisions that apply; 26 less than when the Protocol was first agreed in October 2019 (see Table 1).

4. Changes to EU legislation implementing applicable EU law

The third category of change relates to legislation that implements the regulations, directives and decisions listed in the Annexes to the Protocol. As in the second category – repeal, replacement, and expiry – this type of change is the result of normal EU legislative processes. It also follows from Article 13(3) of the Protocol.

To understand the significance (or otherwise) of this third category it is helpful to first explain what EU ‘implementing’ or ‘delegated’ legislation is and why it exists.

Often EU directives, regulations, and decisions, such as those listed in the Annexes to the Protocol, are written in quite general terms. They are, after all, designed to apply in 27 member states. This means, however, that the original ‘parent’ act does not always set out in sufficient detail all the procedures, processes or requirements that may be necessary to implement its provisions.

So, to avoid unhelpful ambiguity or unconstructive variation in the way a new law is implemented, EU acts often provide for implementing legislation or delegated legislation to be adopted (the difference between implementing and delegated acts just relates to the processes set out for their adoption, the purpose of both is the same, namely, to implement the parent act). Such legislation is always within the scope of a given ‘parent’ legal act, sets out the rules and procedures for its operationalization, is adopted after the original parent act has been passed, and according to its terms.

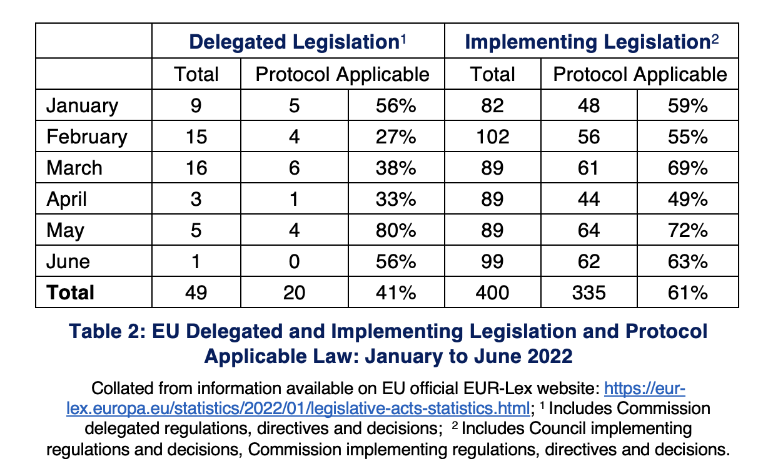

EU implementing legislation – including that relevant under the Protocol – is regularly adopted by either the Commission or the Council. In the first six months of 2022, the EU adopted 599 pieces of implementing legislation. Not all of these apply to Northern Ireland under the Protocol. Of the 599 implementing acts adopted, 355 were within the scope of the Protocol (see Table 2).

Figures for both total implementing acts adopted in January to June this year and the number that are Protocol-applicable may seem high. It is important to note, however, that most implementing acts concern very technical, minor, and specific issues, and they always remain within the scope of the original ‘parent’ act. Moreover, while all implementing acts made under ‘parent’ acts listed in the Protocol and its Annexes are applicable to Northern Ireland, not all of them are significant in terms of policy.

For example, implementing acts will be adopted to correct errors in different language versions of other EU acts: Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/176 made on 9 February 2022 corrects certain language versions of a particular Annex of the Official Controls Regulation (Regulation 2017/625) mentioned earlier and applies under Article 5 and Annex 2 of the Protocol; similarly Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/827 made on 20 May corrects the Danish language version of an Implementing Regulation ((EU) 2019/1842) that concerns arrangements for adjusting allocations of greenhouse gas emission allowances and applies under Article 9 and Annex 4 of the Protocol. While both of these implementing acts make changes to EU acts that apply to Northern Ireland under the Protocol, they have no ‘on-the-ground’ impact.

Some technical changes do have more significance, or potential significance, in and for Northern Ireland. For example, 17 of the EU implementing acts adopted in the first six months of 2022 and which apply under the Protocol concern emergency measures being taken across the EU and in Northern Ireland to address bird flu. While the primary purpose of these 17 implementing acts was very technical – making amendments to lists of geographic regions where bird flu was or had been present – they also concern a very real issue facing the agrifood sector in Northern Ireland, so they are, in this respect, important.

A small number of implementing acts that address Northern Ireland and its position under the Protocol directly have been adopted.

On 21 February, a Commission Implementing Regulation ((EU) 2022/250) was made amending existing EU implementing legislation to introduce a new model of animal health certificate for movements of certain livestock from Great Britain to Northern Ireland which delays the need for certificates regarding scrapie disease to be provided to allow time for GB holdings to be approved as ‘controlled risk’ despite being outside EU regulation.

On 27 April 2022, a Commission Implementing Regulation ((EU) 2022/680) was adopted to amend a standardized poster (provided for in Implementing Regulation ((EU) 2020/178) concerning the bringing of plants, fruits, vegetables, flowers or seeds, into the EU so as to include the ‘United Kingdom (Northern Ireland)’ in the list of non-EU territories for which there is an exemption from the ordinary requirement of a sanitary or phytosanitary certificate for doing so. Again, the actual change here is very minor; however, it reflects the fact that the Protocol has provided for the continued free flow of goods on the island of Ireland, thereby negating the necessity for an SPS certificate that would otherwise be required in view of UK withdrawal from the EU.

While the examples above underline the often very technical nature of provisions made in EU implementing legislation, they also demonstrate the potential for variation in terms of policy significance and sectoral impact in and for Northern Ireland. This is also why changes arising under the Protocol, including via implementing legislation, are very important to track.

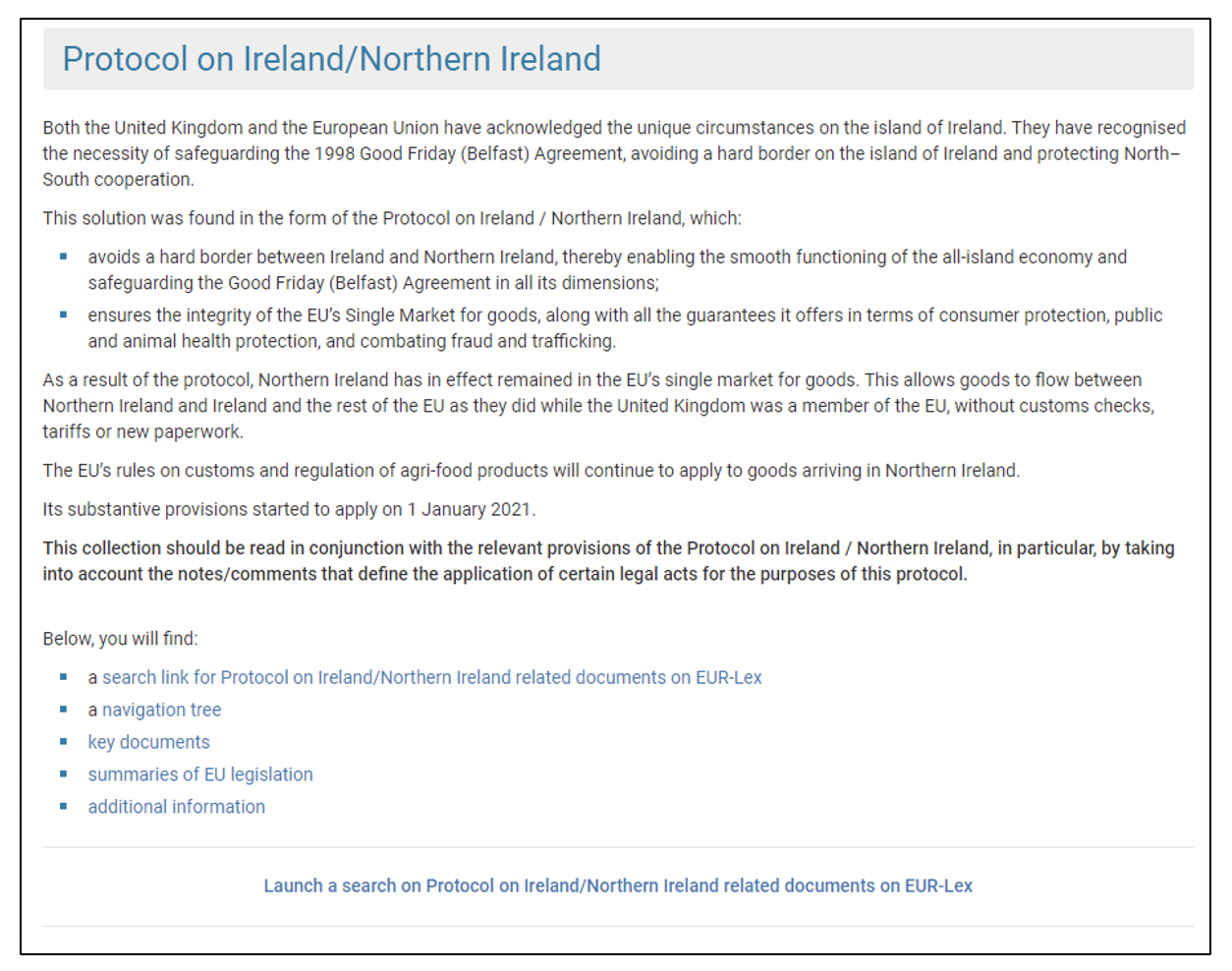

A very positive recent development in this respect is the launch of webpages dedicated to EU law applicable under the Protocol. Established by the European Commission as part of the EUR-Lex website, these pages list all those EU acts that apply to Northern Ireland including ‘parent’ acts, implementing acts, repealed acts, expired acts and replacement acts. This is an important resource for anyone involved in implementing the Protocol or affected by it.

EUR-Lex and the Applicable EU Law

(https://eur-lex.europa.eu/content/news/IENI.html)

5. Research Database of Applicable EU Law

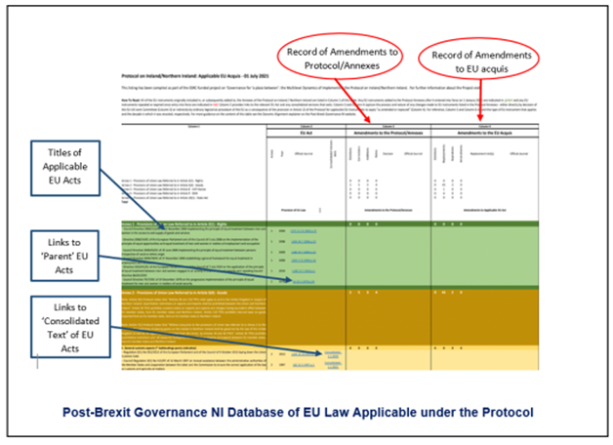

Tracking changes in EU law that applies under the Protocol is a particular focus of the three-year ESRC-funded research project Governance for ‘a place between’: the Multilevel Dynamics of Implementing the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland for which this explainer has been produced.

To this end, it has developed a freely accessible database that provides links to each applicable EU act as well as relevant implementing acts adopted by the EU that can be found through the ‘consolidated text’ versions of the original acts; any additions, amendments, or replacements as well as the deletions and instances where, through expiry, an EU act no longer applies are also recorded. The database contains a list of all of those EU acts that apply in the UK ‘in respect of Northern Ireland’ through the Protocol as of 1 July 2022. It therefore reflects all of the ‘amendments and replacements’ to applicable EU law described in this explainer.

Alongside this, the Post-Brexit Governance NI website maintains lists of relevant UK law that implements Protocol-applicable EU law where this is necessary. While, on this latter issue – domestic legal provisions for the implementation of the Protocol – there is now considerable uncertainty following the introduction of the NIP Bill, it is still important to understand the unique legal arrangements that currently apply to and in post-Brexit Northern Ireland even if these may change in future.

Conclusion: A dynamic democratic challenge

What is clear from this explainer is that implementation of the Protocol involves extensive legislative complexity.

Since the terms of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU were agreed in October 2019, the EU acquis that applies under the Protocol has changed. To date, however, the majority of the most substantive ‘amendments and replacements’ enact changes agreed while the UK was still part of the EU.

This reflects the often-slow pace of EU legislative processes and the fact that the EU acquis that applies in post-Brexit Northern Ireland – primarily concerning trade in goods – is relatively stable. This notwithstanding, ‘amendments or replacements’ made in the second half of 2022, and thereafter, are less likely to have originated while the UK was an EU member state.

This brings us back to the tripartite challenge of practical impacts, democratic accountability, and legislative scrutiny that dynamic alignment and the maintenance of the conditions for the free movement of goods on the island of Ireland poses. These follow from both the novelty of the Protocol’s provisions and the degree of transparency (or lack thereof) surrounding the activities of the three bodies set up to oversee it: the Joint Committee, the Specialised Committee, and the Joint Consultative Working Group (JCWG).

At present, there is limited formal provision for those directly impacted by Northern Ireland’s position under the Protocol – Northern Ireland business, industry stakeholders, rights organisations, and community representatives – to input into the process of dynamic regulatory alignment. That said existing mechanisms, such as the JCWG or respective UK and the EU proposals for greater involvement of NI stakeholders, could provide some opportunity, if realised. Such mechanisms could also be used to convey the position of the UK government in respect of Northern Ireland on proposed EU legislation that the EU may seek to have applied – subject to the agreement of the UK in the Joint Committee – under the Protocol.

While post-Brexit dynamic alignment with the elements of the EU acquis applicable under the Protocol remains a contested issue both between the UK and EU, and in Northern Ireland, lack of provision for direct Northern Ireland input into the adoption of relevant EU acts adds tension to the already difficult task of implementation.

At present, agreement between the UK and EU on some kind of system for enhanced Northern Ireland engagement on EU legislative developments relating to the Protocol looks unlikely. With the introduction of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill in June 2022 on the part of the UK government and the European Commission’s subsequent announcements of revived and new and then additional infringement proceedings, relations between the two sides arguably reached a new low.

Whether and with what amendments, if any, the Northern Ireland Protocol Act is adopted; with its proposed dual regulatory regime, implementation would involve acceptance of dynamic regulatory alignment with some EU law, at least for those goods to be traded across the land border and into the EU market. The need for monitoring therefore remains.

July 2022

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

Dr. Lisa Claire Whitten is Research Fellow on the Governance for ‘a place between’: the multilevel dynamics of implementing the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland at Queen's University Belfast. She can be contacted via: l.whitten@qub.ac.uk.