On the Legislative Complexity to Come

Reflections on What the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the Retained EU Law Bill could mean for Northern Ireland

Lisa Claire Whitten and David Phinnemore

November 2022

Download a copy of this Explainer here

Introduction

During 2022 the United Kingdom (UK) government has introduced two Brexit-related bills into Parliament. The first, the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill (NIPB), exists to deliver the UK’s approach to resolve outstanding issues concerning the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland through, as necessary, unilateral action and therefore in breach of obligations under the Protocol. The second, the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill (REULB), a form of ‘Brexit Freedom’ bill, is designed to remove any remaining EU law from the UK statute book unless there is an express decision to retain it.

The two bills, if passed and implemented, will have significant implications for what laws do and do not apply in the UK. As such they will introduce significant change to the statute book which critics (e.g. Hayward and Fox) claim will add complexity and uncertainty to understanding what laws apply in the UK and, given devolution, where. The result threatens to be particularly complex in the case of Northern Ireland.

To shed some light on the legislative complexity that could come through the two bills, this explainer, considers the complex legislative landscape as it currently stands of Northern Ireland, constitutionally part of the UK but with its own particular form of devolution and subject to the UK’s obligations under the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland. It then considers the implications of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill before turning to the Retained EU Law Bill. A final section considers examples of the separate and combined impacts of the two bills with reference to two specific issues: Northern Ireland’s position in the Single Electricity Market, and the safety and quality of human blood, tissues, and organs for transplantation.

1. The Status Quo Post-Brexit Northern Ireland

The legislative and policy-making landscape of contemporary Northern Ireland is complex. Contributing factors include: the competence and structure of the devolved institutions in Northern Ireland; the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland; and provisions for ‘East-West’ and ‘North-South’ cooperation arising from the 1998 Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement.

a) Devolved Institutions

Devolution in the UK is asymmetric, meaning the governance institutions and the division of competence between central and devolved institutions differ for each constituent part of the UK. Arrangements for devolved government in Northern Ireland are, however, most different. Many points could be made on this subject but, for the purpose of understanding the post-Brexit status quo, two stand out:

-

-

- Functioning devolution in Northern Ireland is contingent on Unionist and Nationalist political parties ‘sharing power’ this renders the institutions vulnerable to collapse due to political parties from one or other ‘side’ refusing to participate.

- The competences of devolved government in Northern Ireland include more areas of policy that (pre-Brexit) were covered by EU law than in any other part of the UK. According to the UK government’s 2021 Common Frameworks Analysis paper, Northern Ireland competences covered 149 policy areas compared to 101 areas in Scotland and 65 areas in Wales.

-

b) Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland

As part of the Withdrawal Agreement (WA), the UK and EU agreed a Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland to address the ‘unique circumstances on the island of Ireland’ in the context of Brexit. As such, the Protocol is designed to: maintain necessary conditions for north-south cooperation, avoid a hard [land] border and protect the 1998 Agreement ‘in all its dimensions’. To this end, the Protocol provides that the UK in respect of Northern Ireland stays dynamically aligned with more than 300 pieces of EU legislation (see our Explainer on Dynamic Regulatory Alignment) as well as other EU acts. These relate primarily to the free movement of goods, but also cover the single electricity market on the island of Ireland.

Read together, provisions in the Withdrawal Agreement (Article 4), the Protocol (Article 12(4); 12(5) and 13(3)) and, in UK law, the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2018 (section 7A), and those EU acts made applicable under the Protocol apply in Northern Ireland as if Northern Ireland were still part of the EU.

Implementation of the Protocol, therefore, has intra-UK divergence implications, particularly in areas where EU acts continue to have effect in Northern Ireland under the Protocol but not in the rest of the UK, i.e. Great Britain (GB).

c) North-South and East-West Cooperation

Under the 1998 Agreement, institutions exist to enable ‘North-South’ cooperation between Northern Ireland and Ireland and ‘East-West’ cooperation between the Ireland and the UK (including its devolved administrations and Crown Dependencies). The outworking of Brexit has changed the context for and potentially complicated cooperation along these two axes. One of the aims of the Protocol was to mitigate the disruptive effect of Brexit on North-South cooperation by providing for some of those EU acts on which existing cooperation relied to continue to apply in Northern Ireland. However, not all areas of North-South cooperation previously underpinned by EU law and policy frameworks are within the scope of the Protocol. Some 61 areas of (pre-Brexit) North-South cooperation are now reliant on equivalence between EU laws in Ireland and retained EU laws in Northern Ireland (see our Explainer on North-South Cooperation).

2. What the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill would… and could… mean for Northern Ireland

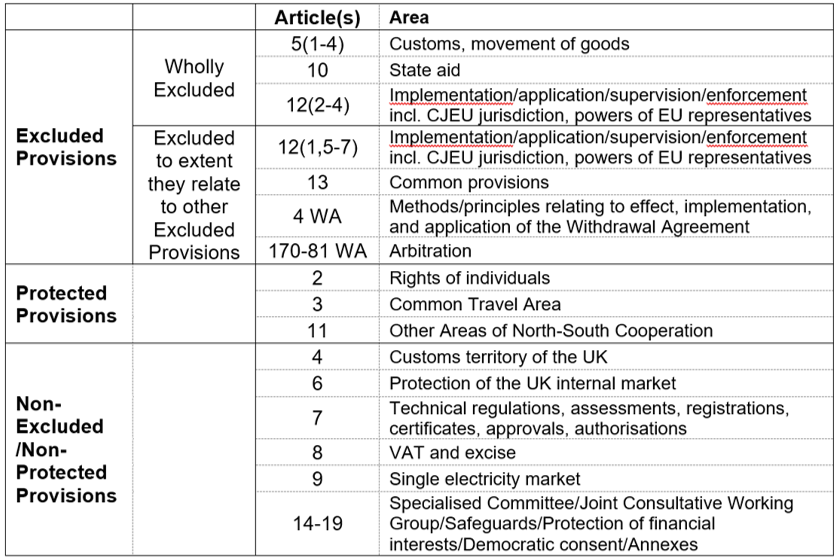

The Northern Ireland Protocol Bill proposes to change the terms of application of the Protocol in the UK. For example, it removes the direct effect of ‘excluded’ provisions in the Protocol and grants UK ministers discretionary powers to make law in these areas. Ministers may also add to or remove from the list of excluded provisions except in a small number of ‘protected’ provisions. If enacted the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill would in effect therefore introduce three new categories of legal provision to the UK in respect of Northern Ireland. These are as follows: ‘excluded’ provisions; ‘protected’ provisions; and provisions that are neither ‘excluded’ nor ‘protected’. Within the ‘excluded’ provisions there would be wholly excluded provisions and provisions that are excluded to the extent that they relate to other excluded provisions.

In introducing these new categories, the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill would change in domestic UK law the arrangements for the enforcement of the Protocol and those EU acts it makes applicable in Northern Ireland.

Arrangements set out in the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill regarding enforcement are not straightforward, but they are important for understanding the Bill’s implications for law and policy in Northern Ireland.

First, the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill ‘excludes’ any provision of the Withdrawal Agreement/Protocol if, and to the extent that, it confers jurisdiction on the EU’s Court of Justice (CJEU) (clause 13(1) NIPB). The removal of CJEU jurisdiction here applies to ‘excluded’ provisions and/or ‘any other matter’ regarding the Withdrawal Agreement/Protocol, meaning it applies in relation to non-‘excluded’, and potentially ‘protected’ provisions.

Alongside removing CJEU jurisdiction, the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill would exclude from UK law a number Withdrawal Agreement/Protocol provisions those that currently provide for the Protocol’s implementation and enforcement in accordance with provisions of EU law in ‘so far as’ those provisions apply in relation ‘to any other excluded provision’ (clause 14(1) NIPB). Further, if enacted, the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill would remove any obligation on UK Courts to follow CJEU case law in relation to the Protocol/Withdrawal Agreement as well as the ability of UK Courts to refer cases to the CJEU.

Importantly, in relation to all provisions made in the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill concerning enforcement of the Protocol/Withdrawal Agreement UK government ministers are empowered to make ‘any provision’ they ‘consider appropriate’ in relation to enforcement. The purpose of regulations made by ministers under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill could therefore include requiring UK authorities to:

-

- make arrangements with the EU for supervision of the implementation of the Protocol/Withdrawal Agreement (clause 13(5)(a))

- share data with the EU regarding the Protocol (clause 13(5)(b))

- implement and apply EU laws (clause 14(3)(a))

- interpret the Protocol/Withdrawal Agreement in accordance with methods and general principles of EU law and CJEU case law (clause 14(3)(b)

- refer a question of interpretation of EU law to the CJEU (clause 20(4)).

What this means is that while the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill provides for the disapplication of general principles of EU law and related EU law enforcement mechanisms (including the CJEU) that currently apply in the UK under the Protocol, it also gives UK ministers the power to reapply those same EU law principles and enforcement mechanisms if they consider it appropriate to do so.

3. Add in the Retained EU Law Bill…

Importantly, EU laws made applicable under the Protocol, Protocol-applicable law, are not retained EU law. The EU Withdrawal Agreement Act (EUWA) 2018 defines retained EU law as any enactment that had effect immediately before the end of the UK transition period as a consequence of the (now repealed) European Communities Act (ECA) 1972 which gave EU law had direct effect in the UK during its EU membership (section 2(2) and schedule 2 paragraph 1A of ECA 1972); the EUWA Act 2018 explicitly excludes from this definition any EU instruments made applicable by the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement (and so the Protocol) (see section 3(2) EUWA 2018 read together with section 7A(1) EUWA 2018).

Protocol-applicable EU law has legal effect in the UK as a consequence of section 7A of the EUWA Act 2018 read together with the provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement (in particular Article 4) and the Protocol. So, these two categories of law retained EU law and Protocol-applicable EU law have different legislative sources; this is important to understand as we consider the possible implications of the Retained EU Law Bill for Northern Ireland.[1]

The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill (REULB) provides for the ‘overhaul’ of the EUWA Act 2018 in so much as it relates to retained EU law. As introduced, the Bill contains a ‘sunset’ clause whereby most retained EU law would expire at the end of 2023, while at the same time enabling UK ministers to ‘exempt’ secondary retained EU law from the ‘sunsetting’ provision. Provision is also made for central UK government ministers to postpone until June 2026 application of the sunset provision. The only type of retained EU law not subject to ‘sunsetting’ would be primary acts of UK law that implement EU law (e.g., Equality Act 2010; Health and Safety at Work Act 1974). From the end of 2023, these retained EU laws would be renamed ‘assimilated’ law.

The Retained EU Law Bill also gives UK ministers and devolved authorities power to, by regulations, revoke, restate, replace or update retained EU law and to remove or downgrade existing forms of parliamentary scrutiny of secondary legislation when it is being used to this end.

On the application of EU law principles, the Retained EU Law Bill provides for the removal of the principle of supremacy and other general EU law principles from the UK after 2023. It would also establish a new legal framework for UK courts to determine applicable law after 2023 if/when restated (retained) or assimilated EU laws are included.

4. … and what the Retained EU Law Bill would … and could… mean for Northern Ireland

The Retained EU Law Bill has several important implications for Northern Ireland, particularly when read in the light of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the current complexities arising out of the distinct arrangements for devolved government and legislation in Northern Ireland.

What follows is a non-exhaustive list of some of the complexities, contradictions, and tensions created by the Retained EU Law Bill.

a) Dis-Application of Principles of EU Law

Clause 4(1) REULB proposes to insert a new section (A1) to section 5 EUWA 2018 to provide that, after the end of 2023, the ‘principle of the supremacy of EU law is not part of [UK] domestic law’.

This conflicts with provisions in the Withdrawal Agreement and related provisions in the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill.

Under Article 4(1) WA, read together with section 7A(1) EUWA 2018, any EU laws made applicable in the UK under the Withdrawal Agreement, or its Protocols, have the same effect as they would in an EU Member State, i.e. they enjoy direct effect, supremacy, and the general principles of EU law apply.

So, the introduction via the Retained EU Law Bill of a new clause 5(A1) EUWA 2018 would (presumably) change this by disapplying ‘supremacy’ from the UK statute, thus undermining section 7A EUWA 2018 on the implementation of the Protocol and EU laws it makes applicable under Article 4 WA under which direct effect, supremacy, and general principles of EU law have effect.

While the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill proposes to remove, in effect, the application of EU laws listed in the Protocol and its Annexes from CJEU jurisdiction, it also, under clause 14 NIPB, grants UK ministers the power to make provision for those laws to be interpreted in accordance with EU general principles and/or CJEU case law.

Clause 4(1) REULB therefore appears to conflict with clause 14 NIPB.

b) Sunsetting retained EU Law

Clause 1(1) REULB the ‘sunset’ clause has implications for Northern Ireland in relation to areas of policy currently within the scope of the Protocol and outside the scope of the Protocol but in the scope of retained EU law.

c) The Retained EU Law Bill and Policy Areas within the Scope of the Protocol

Some EU acts applicable in Northern Ireland under the Protocol only partially apply. These include: the Single Use Plastics Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/904); Regulation (EU) 536/2014 and Directive 2009/35/EC on clinical trials for medicines; two regulations on the organisation of agricultural markets (Regulation (EU) 1308/2013 and Regulation (EU) 1306/2013); and EU acts on the regulation of energy and electricity markets (see Annex 4 of the Protocol).

In relation to these instruments, clause 1(1) REULB read together with the Protocol and EUWA section 7A EUWA 2018 suggests that to the extent that these instruments still apply they could be partially ‘sunset’ in domestic law. As seen in the examples below (see 5a and 5b), this will likely lead to a complex and convoluted policy landscape in and for Northern Ireland.

For EU acts made applicable in Northern Ireland under the Protocol but which are also ‘excluded’ provisions in the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, the Retained EU Law Bill raises the question as to whether Protocol-applicable EU law also has retained EU law status and would therefore be subject to ‘sunsetting’ if/when, under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, UK ministers ‘excluded’ them as Protocol-applicable EU law.

While this may sound overly technical, the answer to this question is potentially very significant for officials and stakeholders in Northern Ireland seeking to manage the legislative transformation these two Bills envisage.

If, as a literal reading of the proposed legislation would suggest, there are retained EU law versions of what are now Protocol-applicable EU acts, then notwithstanding actions taken by UK government ministers under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, those retained EU law versions could, in theory, be ‘restated’ by either devolved or UK government ministers under the Retained EU Law Bill.

If there are no retained EU law versions of what are, currently, Protocol-applicable acts, actions taken under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill by UK government ministers will have greater policy significance given that, by extension, powers granted to devolved ministers in Northern Ireland under the Retained EU Law Bill are more limited than powers granted to devolved ministers in Scotland and Wales This is because ministers in Scotland and Wales, in contrast to counterparts in Northern Ireland, would be able to take action in areas of retained EU law that would have been Protocol-applicable EU law in Northern Ireland but which have been excluded under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and under it are therefore subject to UK government ministers’ discretionary powers.

d) Retained EU Law Bill and Areas Not in Scope of the Protocol

One of the most important aspects of the Retained EU Law Bill in and for Northern Ireland relates to its implications for North-South cooperation which relies to significant extent on retained EU law. Of the 142 areas of such cooperation identified in 2017 by the UK and EU as being underpinned by EU law and policy frameworks, the legal underpinning for 61 areas of cooperation are not protected via the Protocol and the EU acts it makes applicable to the UK in respect of Northern Ireland.

Ongoing cooperation in these 61 areas, therefore, relies to a large extent on the continued equivalence of law and policy in Ireland and Northern Ireland that arises from EU law and policy on one side of the land border and retained EU law and policy on the other.

Removing or ‘sunsetting’ retained EU law in respect of Northern Ireland in these areas of existing cooperation would remove that equivalence. If realized, the ‘sunsetting’ of relevant retained EU law would arguably undermine legislative provisions made elsewhere for the protection of North-South cooperation including in:

-

-

- Section 10 EUWA 2018 whereby ministers making provisions regarding retained EU law (under section 8 EUWA 2018) cannot do anything to ‘diminish any form of North-South cooperation provided for by the Belfast Agreement’

- Article 11 Protocol which provides for the Protocol to be implemented and applied such that the necessary conditions for North-South cooperation are maintained including in relation to the environment, health, agriculture, transport, education and tourism, energy, telecommunications, broadcasting, inland fisheries, justice and security, higher education, and sport

- Clause 15(3) NIPB which provides for the ‘protection’ of Article 11 Protocol

- The 1998 Agreement provisions for North-South cooperation.

-

5. What would the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill combined with Retained EU Law Bill mean for Northern Ireland?

If adopted as introduced to Parliament, the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the Retained EU Law Bill would individually and more so together add considerable complexity and uncertainty to the legislation that applies to and in Northern Ireland. That complexity can be illustrated through two case studies that consider some of the more obvious questions that the bills would raise with regard to: (a) Northern Ireland’s position in the Single Electricity Market on the island of Ireland; and (b) the safety and quality of human blood, tissues, and organs for transplantation in Northern Ireland.

a) Northern Ireland’s position in the Single Electricity Market

Status Quo: Under Article 9 Protocol, seven EU acts governing wholesale electricity markets set out in Annex 4 apply to the UK in respect of Northern Ireland ‘insofar as’ they are necessary for the joint operation of the single wholesale electricity market in Ireland and Northern Ireland. Article 9 Protocol is explicit that these seven acts partially apply.

Northern Ireland Protocol Bill: Under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, neither Article 9 of the Protocol nor Annex 4 is either ‘protected’ or ‘excluded’. This means that, if the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill becomes law as currently drafted, the seven EU acts contained in Annex 4 and made applicable by Article 9 would not be ‘excluded’ from domestic law and therefore would continue to have legal effect in the UK although, according to clause 13 NIPB, they would then do so outside the jurisdiction of the CJEU. This would be the case unless UK ministers decided otherwise. Using powers provided by clauses 13(5), 14(3) or 20(4) NIPB, ministers could, by regulation, make provision in relation to the continued application of EU laws made applicable under Article 9 of the Protocol, including introducing procedures for the referral of issues of interpretation and/or enforcement to the CJEU. Alternatively, using clause 15 NIPB, UK ministers could, by regulation, make provisions to ‘exclude’ Article 9 and Annex 4 thereby removing their effect in domestic law.

Retained EU Law Bill: Under the Retained EU Law Bill, all seven EU acts in Annex 4 and made applicable by Article 9 Protocol are retained EU law in GB and, to the extent that they are not covered by the Protocol, in Northern Ireland. These retained EU law versions of the Annex 4 acts would therefore be subject, if the Bill were enacted, to the sunset provisions of clause 1(1) REULB unless provision existed for their continued application either through UK legislation made to replace the relevant acts or the Protocol and section 7A EUWA 2018 (even as amended by clause 2 NIPB).

Status Quo + Northern Ireland Protocol Bill + Retained EU Law Bill: The complexities that would be created for Northern Ireland in relation to the Single Electricity Market by the adoption of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the Retained EU Law Bill are best demonstrated through specific legislative examples:

-

-

- One of the EU acts listed in Annex 4 is Regulation (EC) No 714/2009 of 13 July 2009 on conditions for access to the network for cross-border exchanges in electricity and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1228/2003. On 31 December 2019, this Regulation was repealed by the EU and replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/943. The new Regulations was explicit in stating that any references to the repealed regulation “shall be construed as references to” the replacement regulation.

- Under Article 13(3) Protocol, EU acts listed in the Annex are to apply “as amended or replaced” in Northern Ireland. Consequently, new Regulation (EU) 2019/943 is applicable in UK(NI) “insofar as” it relates to the operation of the Single Electricity Market. Adopted towards the end of the post-Brexit ‘transition period’, Regulation (EU) 2019/943 applies in Great Britain as ‘retained EU law’; according to the UK government dashboard on retained EU law, it currently (November 2022) exists as ‘unchanged’ retained EU.

-

Taking the above context into account, questions arise in relation to substance and procedure:

-

-

- If those EU acts in Annex 4 that partially apply in Northern Ireland under the Protocol are subject to the sunset clause in the Retained EU Law Bill, how will they be redrafted to reflect their continued, stripped-back application?

- If those EU acts law in Annex 4 that partially apply in Northern Ireland under the Protocol are not subject to the sunset clause in the Retained EU Law Bill, what is the legal basis for this to be the case?

-

The operation of the Single Electricity Market on the island of Ireland is a complex but very important area of public policy for Northern Ireland. Additional complexity, coupled with legal uncertainty, are unlikely to be welcomed.

b) Safety and Quality of Human Blood, Tissues, and Organs for Transplantation

Status Quo: Under Article 5(4) Protocol, three EU acts regarding the quality of and safety procedures concerning human blood, human tissues and human organs intended for transplantation apply to the UK in respect of Northern Ireland. These are Directives 2002/98/EC, 2004/23/EC, and 2010/53/EU. The application of these acts reflects their role in underpinning cross-border cooperation in healthcare and the shared aim of the UK and EU negotiators to avoid any physical checks on the land border.

Northern Ireland Protocol Bill: Under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, Article 5(4) Protocol is ‘excluded’ from application in UK law. If the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill is enacted, therefore, the continued domestic effect of provisions that currently exist in UK law for Northern Ireland regarding the quality and safety of human blood, tissues and organs intended for transplantation and which flow from EU law will be subject to the discretion of central UK government ministers. Additionally, these instruments will likely no longer be updated in line with amendments to and replacements of the relevant EU law in line with Article 13(3) Protocol on dynamic alignment as it is also ‘excluded’.

In 2019, four Statutory Instruments (SIs) were passed (using powers granted by section 8 EUWA 2018) to amend existing domestic legislation which gave effect to the three EU Directives noted above regarding safety and quality of blood, tissues, and organs for transplantation:

-

-

- The Blood Safety and Quality (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations (SI 2019/4)

- The Quality and Safety of Organs Intended for Transplantation (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations (SI 2019/483)

- The Human Tissue (Quality and Safety for Human Application) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations (SI 2019/481)

- The Human Fertilisation and Embryology (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations (SI 2019/482)

-

Their adoption was to ensure that domestic law in these areas continued to operate effectively after UK withdrawal even in the event of a ‘no deal’ exit. The SIs applied across the whole of the UK.

Following the conclusion of the Withdrawal Agreement and Protocol, four more SIs were passed in 2020 to amend the 2019 SIs so as to “restrict the changes made by the 2019 SIs to Great Britain (GB) only”:

-

-

- The Blood Safety and Quality (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/1304)

- The Quality and Safety of Organs Intended for Transplantation (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/1305)

- The Human Tissue (Quality and Safety for Human Application) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/1306)

- The Human Fertilisation and Embryology (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2020 (SI 2020/1307)

-

The accompanying Explanatory Memorandum noted that the new SIs would “retain a single set of UK rules, but within them, a small number of provisions will apply to NI or GB only”.

The prospect of UK ministers ‘excluding’ the three EU directives under clause 4(2) NIPB exposes the tension within the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill as regards the ‘protection’ of North-South Cooperation (Article 11 Protocol) and the disapplication of EU laws which currently underpin such cooperation including, in this instance, in relation to cross-border delivery of healthcare. This raises important questions about the implications, for example, of excluding the three EU directives for the operation of the All-Island Congenital Heart Disease Network and the North-West Cancer Centre. Both of which provide specialist healthcare on a cross-border and all-island basis and therefore rely on shared law and policy provisions, including those provided by the application of the three EU Directives that form part of Protocol-applicable EU law in Northern Ireland (see the findings of the 2017-18 UK-EU mapping exercise, specifically areas 10, 11 and 100).

Retained EU Law Bill: Under the Retained EU Law Bill, all three EU Directives noted above and made applicable by Article 5(4) Protocol Directives 2002/98/EC, 2004/23/EC, 2010/53/EU noted are retained EU law as they apply in GB and therefore would be subject, if the Bill is enacted, to the sunset provisions of clause 1(1) REULB unless provision exists for their continued application either through UK legislation made to replace the relevant acts, or through the Protocol and section 7A EUWA 2018 (even as amended by clause 2 NIPB).

In view of the amendments introduced first by the four 2019 SIs, followed by the four 2020 SIs, questions about whether or not retained EU law versions of Protocol-applicable EU law exist come into play. If, under Northern Ireland Protocol Bill, the four 2020 SIs are disapplied in domestic law so as to reflect the ‘exclusion’ of the three Directives they enact as Protocol-applicable EU law, it may be the case that the applicable legislation in respect of Northern Ireland reverts to the retained EU law version laid down in the 2019 SIs. The 2019 retained EU law SIs could then, in theory, be ‘restated’ under the Retained EU Law Bill doing so would arguably implement the ‘protection’ of Article 11 Protocol under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill as well as respect the requirement under section 10 EUWA 2018 ‘not to diminish’ any form of North-South cooperation. This example again underlines the possible interplay of decisions taken by Ministers under the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the decisions taken by Ministers under the Retained EU Law Bill. As drafted, neither of the two texts includes a mechanism or procedure by which Ministers acting under one Bill could or should consult the relevant Minister(s) acting under the other Bill. Coordination would be needed to ensure legislative certainty.

6. Conclusion: Complexity and Contingency

The content of this explainer is speculative. The points made and questions raised here are based on a literal reading of existing law applicable in and for Northern Ireland some of which is the focus of ongoing UK-EU talks and therefore could change and two pieces of proposed domestic legislation currently being considered by Parliament: the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the Retained EU Law Bill. As such, the essential purpose of this explainer has been to illustrate some of the additional legal complexities and uncertainties that could be created in and for Northern Ireland if these two new Bills become law.

Given the persistently ‘unique circumstances’ of Northern Ireland in the post-Brexit era, if/when either or both of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the Retained EU Law Bill become(s) law, it is extremely like that particular challenges will arise for Northern Ireland. This being so, systematic consideration of the detailed implications of what the Bills would entail in terms of legal clarity and certainty in and for Northern Ireland would seem wise. A failure to address the implications would only add to the increased legal complexity that characterises post-Brexit Northern Ireland.

November 2022

Download a copy of this Explainer here.

[1] For more on the relationship between retained EU law and Protocol-applicable EU law see: Phinnemore, D. and Whitten, L. C. ‘Retained EU Law: Where next?’, evidence submitted to House of Commons European Scrutiny Committee, 28 April 2022.