Dynamic Regulatory Alignment and the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland - Three Year Review

Lisa Claire Whitten

March 2024

Download a copy of this Explainer here

Executive Summary

-

- Under the Protocol/Windsor Framework, aspects of EU law continue to apply to Northern Ireland despite the UK no longer being in the EU.

- Those EU laws that still apply in Northern Ireland do so ‘as amended or replaced’ by the EU; this enables Northern Ireland goods to continue to move freely on the island of Ireland and into the rest of the EU internal market.

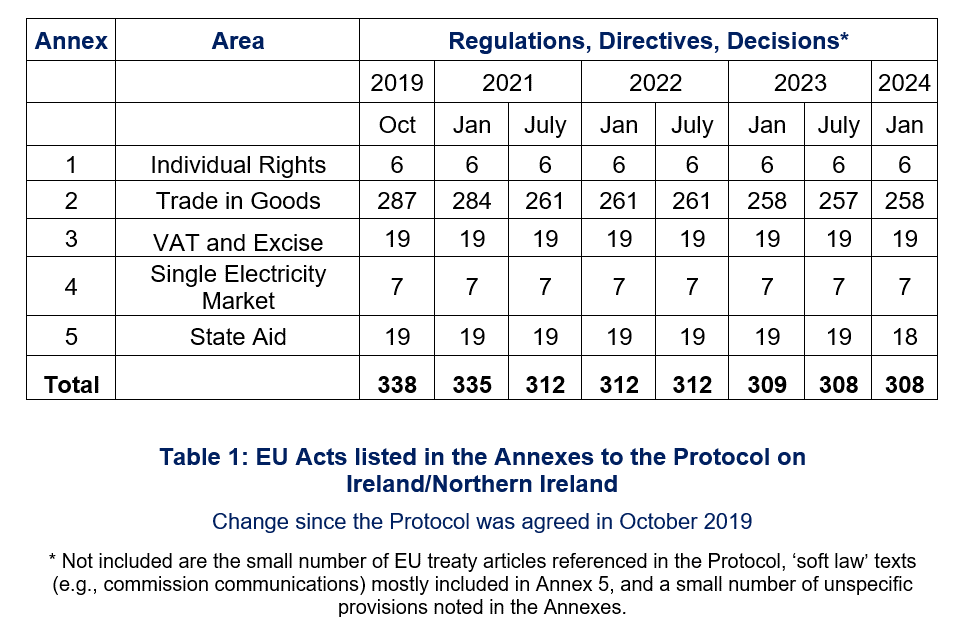

- The extent of EU law applying in Northern Ireland since the Protocol was agreed in October 2019 has changed.

- 12 EU acts have been added to the list of applicable EU laws; two EU acts have been deleted; and four EU acts have expired.

- 62 EU acts have been repealed; 28 EU acts have replaced them, only six of which were adopted after the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020.

- As of 1 January 2024, 308 EU acts (i.e., regulations, directives, or decisions) apply in Northern Ireland; this is a decrease from the 338 EU acts listed in the Protocol as originally agreed.

- The EU regularly adopts amendments and replacements to EU acts applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework and to associated implementing acts; these amendments and replacements automatically apply in Northern Ireland.

- Tracking the evolution of applicable EU law and its potential implications for Northern Ireland is a complex but important task; some measures taken under the Windsor Framework and Safeguarding the Union may prove helpful in this regard.

Introduction

Northern Ireland occupies a unique position in the relationship between the United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union (EU). The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland provides that aspects of EU law continue to apply in Northern Ireland despite it having left the EU with the rest of the UK on 31 January 2020.

Under the terms of the Protocol, Northern Ireland remains part of the UK customs territory. However, the EU customs code applies in respect of Northern Ireland as do specific EU acts that regulate certain individual rights, free movement of goods, VAT and excise, state aid and electricity markets. New EU acts that fall within the scope of the Protocol may also be added to those that apply in Northern Ireland.

Moreover, the Protocol requires that amendments or replacements to these acts apply in Northern Ireland. Such dynamic regulatory alignment is necessary to maintain the free movement of goods on the island of Ireland. However, this has proved politically controversial, not least because it involves EU acts applying in Northern Ireland in which, after Brexit, neither the UK nor Northern Ireland has had a direct role in adopting.

In February 2023, after months of talks over the implementation of the Protocol, the UK and EU announced the conclusion of the Windsor Framework – a package of measures designed to provide “practical and sustainable measures” that the UK Government and the European Commission considered “necessary to address, in a definitive way, unforeseen circumstances or deficiencies” that had emerged since the Protocol took legal effect. This announcement came one year after the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) had collapsed the devolved institutions in Northern Ireland in protest against the implementation of the Protocol as originally agreed. Among the intended aims of the Windsor Framework was therefore to provide assurance to the DUP sufficient for the party to agree to re-enter power-sharing government in Northern Ireland.

In substance, the Windsor Framework constitutes a body of legal and political texts which provide for the introduction of a series of easements on customs checks and regulatory requirements on goods entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain and remaining in Northern Ireland. It also allows for a range of specific derogations to be introduced that address GB-NI movements of certain goods, these include new provisions for the movement of pets, parcels, seed potatoes, certain plants and plant products, medicines for human use, and agrifood products.

In the Windsor Framework the UK and EU also made a range of commitments regarding the involvement of NI stakeholders in the implementation of the Protocol. Prominent among this category of changes was the introduction of so-called ‘Stormont Brake’ mechanisms which allow members of the NI Assembly (MLAs) to seek the application by the UK government of a ‘brake’ to otherwise automatic updates to certain EU acts that apply under the Protocol if/when they judge that the relevant update would have a “significant impact specific to everyday life of communities in Northern Ireland in a way that is liable to persist” (new Article 13(3a) Protocol/Windsor Framework). Additionally, when implementing this aspect of the Windsor Framework in domestic law the UK government laid down in a draft statutory instrument that, subject to the restoration of the NI devolved institutions, it would not be able agree to a new EU act being added to the Protocol without first achieving cross-community consent in the NI Assembly, unless ‘exceptional circumstances’ exist.

This explainer reviews the substance of the first three years of dynamic regulatory alignment with those elements of EU law that still apply in post-Brexit Northern Ireland. The content builds on five previous reviews carried out after the first six months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months and 30 months, following the Protocol’s entry into force.

The extent of overall change after three years does not differ much from that presented after 30 months, nor indeed after 24 months, 18 months or 12 months; this is itself an important finding. The absence of significant change between 2021 and 2023 reflects the slow pace of the EU legislative process and the relative stability of the specific set of EU acts that continue to apply in the UK in respect of Northern Ireland.

Regular minor amendments and technical updates to EU implementing legislation also apply to Northern Ireland. While many have little or no impact in Northern Ireland in terms of policy, some do have implications for industry and stakeholders with some changes also requiring dedicated domestic law to implement them. The wide variation in terms of policy impact of – sometimes frequent – amendments and updates to applicable EU law underlines the ongoing importance of monitoring the legal and practical implications of the unique position of Northern Ireland post-Brexit.

Given the generally slow pace of change, the policy impacts of dynamic regulatory alignment for Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework are not as extensive as they could be. This is not to say dynamic regulatory alignment is without its challenges in respect of the practical impacts for industry, democratic accountability, and legislative scrutiny. Moreover as time goes on and more changes are made in other parts of the UK in areas of law in which EU laws still apply in Northern Ireland, the potential for tangible policy impacts of its dynamic regulatory alignment increases. Following a review of the first three years of implementation, the conclusion to this explainer returns to consider possible future implications of the challenges and opportunities facing Northern Ireland under these unique arrangements.

1. A new regulatory dynamic for Northern Ireland

Under Article 13(3) Protocol/Windsor Framework, EU acts listed in its Annexes apply ‘as amended or replaced’ to the UK in respect of Northern Ireland. When the Protocol was agreed by UK and EU negotiators as part of the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement in October 2019, 338 acts were listed in the Annexes of the legal texts. Under the Protocol/Windsor Framework, additions can be made (under Article 13(4)), and acts can also be deleted.

These arrangements put Northern Ireland in a position of ‘dynamic alignment’ with a specified but potentially evolving selection of the EU ‘acquis’, the body of legal and other agreed obligations and commitments that apply to, and in, EU member states.

In implementing the Protocol/ Windsor Framework, therefore, the UK has committed to keeping Northern Ireland aligned with changes made to the EU acts that are included in its scope.

Three years after the Protocol/Windsor Framework entered into force, how has the body of EU law that applies to, and in, Northern Ireland changed?

Like many issues in the post-Brexit world, the answer is not simple. Several types of change have taken place. They fall into four broad categories:

-

- additions to and deletions from the Protocol/Windsor Framework Annexes

- repeal, replacement, and expiry of applicable EU law

- amendments to applicable EU law

- changes to EU legislation that implements applicable EU law.

2. Additions to and deletions from the Annexes to the Protocol

The first category of change concerns the specific EU acts that apply in Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Through the EU-UK Joint Committee set up to oversee the implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement, the UK and the EU can, by agreement, add new EU acts that fall within the scope of the Protocol/Windsor Framework to the relevant Annexes (Article 13(4)). The EU-UK Joint Committee can also remove acts listed.

Before the end of the 11-month transition period that followed the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, the UK and EU agreed in December 2020 to add eight EU acts to Annex 2 of the Protocol. It also agreed to remove two EU acts listed in the same Annex.

Of the eight acts added, five related to legislation that the EU-UK Joint Committee decided, following review, should have been included in the original text of Annex 2. The five acts that were added concern:

-

- rules for monitoring trade between the EU and third countries in drug precursors (Council Regulation (EC) 111/2005);

- use of indications or marks to identify the lot – or batch – to which food products belong (Directive 2011/401/EU);

- rules on the marketing of fodder plant seed (Council Directive 66/401/EEC);

- rules on the marketing of propagating material of ornamental plants (Council Directive 98/56/EC); and

- rules on the marketing of vegetable propagating and planting material other than seed (Council Directive 2008/72/EC).

The three other additions were new EU acts adopted since the content of the Protocol/Windsor Framework had initially been agreed in November 2018. The EU-UK Joint Committee decided that the following three acts fell within the scope of the Protocol/Windsor Framework, so added these to Annex 2:

-

- bilateral safeguard clauses and other mechanisms for the temporary withdrawal of preferences in certain EU trade agreements with third countries (Regulation (EU) 2019/287);

- measures to reduce the impact of certain plastic products on the environment (Directive (EU) 2019/904); and

- and measures to control the introduction and import of cultural goods (Regulation (EU) 2019/880).

The two acts that were removed by the EU-UK Joint Committee concerned CO2 emissions standards for passenger cars (Regulation (EC) 443/2009) and light-duty commercial vehicles (Regulation (EU) 510/2011). Their original inclusion was deemed unnecessary.

Taking these changes into account, when the Protocol/Windsor Framework entered into force on 1 January 2021 following the end of the transition period, 344 EU acts were listed in its Annexes.

Since UK and EU agreed the Windsor Framework in February 2023, and prior to the conclusion of the Safeguarding the Union deal between the DUP and UK Government in February 2024, the EU-UK Joint Committee agreed to add four new acts to those already listed in Annex 2 of the Protocol/Windsor Framework.

In July 2023 two recently adopted EU acts were added by UK-EU agreement. Both followed directly from UK-EU agreement on the Windsor Framework:

-

- specific rules relating to medicinal products for human use intended to be placed on the market in Northern Ireland (Regulation (EU) 2023/1182);

- specific rules relating to the entry into Northern Ireland from other parts of the United Kingdom of certain consignments of retail goods, plants for planting, seed potatoes, machinery and certain vehicles operated for agricultural or forestry

purposes, as well as non-commercial movements of certain pet animals into Northern Ireland (Regulation (EU) 2023/1231).

In September 2023, the UK and EU agreed to add another two newly adopted EU acts to those already listed in the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Neither specifically addressed Northern Ireland; instead they concerned:

-

- temporary trade liberalisation measures supplementing trade concessions applicable to Ukrainian products under the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement (Regulation (EU) 2023/1077);

- temporary trade liberalisation measures supplementing trade concessions applicable to products from the Republic of Moldova under the EU-Moldova Association Agreement (Regulation (EU) 2023/1524).

3. Repeal, replacement, and expiry of applicable EU Law

The second category of change covers the repeal, replacement, and expiry of EU acts – regulations, directives, and decisions – listed in the Annexes to the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Changes in this category are the result of normal EU legislative processes and follow from the provision in Article 13(3) Protocol/Windsor Framework stating that relevant EU acts apply as ‘amended or replaced’ to and in Northern Ireland.

Of the 338 EU acts originally listed in the Annexes, 62 had been repealed as of 1 January 2024. Only three of these had been repealed in the preceding six months.

Most, but not all, of the repealed EU acts have been directly replaced by a new piece of EU legislation. This is because several replacement acts consolidate provisions previously spread over various pieces of (now repealed) legislation into one or two new, more comprehensive, acts. The 62 repealed acts have been replaced by 28 new or replacement acts.

In most instances, even three years after the UK withdrew from the EU, this dynamic alignment concerns changes to pieces of EU legislation adopted when the UK was in the EU. Of the 28 replacement acts, only six were adopted after the UK left the EU on 31 January 2020 – one in 2020 (Regulation 2020/740); two in 2021 (Directive (EU) 2021/555 and Regulation (EU) 2021/821); one in 2022 (Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/2473); and two in 2023 (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2835 and Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2831) – of these, only five were adopted after 1 January 2021 and therefore after the end of the UK Transition Period when changes to EU law ceased to have effect in the UK as a whole. More details about replacement EU acts content and date of adoption are listed below.

The changes laid down in the Animal Health Law were agreed in March 2016, so before the UK’s EU referendum and therefore with the UK taking full part in their adoption. The adopted text included transitional measures and allowed for the repeal of earlier acts to take effect in April 2021.

As a supplement to the 2016 Regulation, the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/687 sets out measures to prevent and control the spread of certain diseases. The relevant diseases were listed in the 2016 Regulation but required more specific provisions; these are laid down in the 2020 Delegated Regulation.

In a similar way, seven of the other repealed acts concerned EU rules on official controls and checks on food and feed, animal health and welfare standards, plant health and plant protection. These were replaced by a single overarching EU act: Regulation (EU) 2017/625, known as the ‘Official Controls Regulation’. It incorporates and updates pre-existing provisions in the repealed acts. It was agreed in April 2017, shortly after the UK triggered Article 50 announcing formally its intention to withdraw from the EU and so with the UK participating in the regulation’s adoption. The new act (Regulation (EU) 2017/625) included transitional measures and allowed for the repeal of the seven earlier acts to take effect in December 2019.

Also repealed in the last three years have been two directives – Council Directive 93/42/EEC and Council Directive 90/385/EEC – concerning the production of and trade in medical devices – the repeal took effect in May 2021. This change had been provided for in Regulation (EU) 2017/745 which was agreed while the UK was still an EU Member State and was listed in Annex 2 to the Protocol/Windsor Framework, so the repealed directives were not replaced directly. Addressing the same area of policy, the repeal of Directive 98/79/EC – concerning in vitro medical devices – had been provided for Regulation (EU) 2017/746 which was also listed in Annex 2, and agreed during the UK’s EU Membership, but the change took effect in May 2022.

In addition, two regulations concerning requirements for the use of statistics on trade in goods between EU member states and with non-EU countries – Regulation (EC) No 638/2004 and Regulation (EC) No 471/2009– have been repealed and replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/2152 on European business statistics. The latter incorporates and updates requirements from the earlier acts. The new regulation was agreed in November 2019, when the UK was still an EU member state; it also included transitional measures for the scheduled repeal of earlier acts to take effect at the end of 2021.

Of the remaining acts, 16 have been repealed and replaced directly, 11 of these were repealed before the end of the first year of the Protocol/Windsor Framework’s implementation, four were repealed during the second year, and one was repealed during the third year of implementation.

Those repealed and replaced in 2021 concern:

-

- the approval and market surveillance of motor vehicles and related products (Directive 2007/46/EC) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2018/858 adopted in June 2018 and taking effect in August 2020;

- controls on cash entering or leaving the EU (Regulation (EC) 1889/2005) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2018/1672 adopted in November 2018 taking effect in June 2021;

- controls on trade in goods that could be used in capital punishment or torture (Council Regulation (EC) 1236/2005) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/125 adopted in January 2019 and taking effect in February 2019;

- the mutual recognition of goods between member states (Regulation (EC) 764/2008) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/515 adopted in March 2019 and taking effect in April 2020;

- controls on persistent organic pollutants (Regulation (EC) 850/2004) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 adopted in June 2019 and taking effect in July 2019;

- the marketing and use of explosives precursors (Regulation (EU) 98/2013) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1148 adopted in July 2019 and taking effect in January 2021;

- provisions for the conservation of fisheries and marine ecosystems (Council Regulation (EC) 850/98)replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1241 adopted in July 2019 taking effect in August 2019;

- provisions for computerising the movement and surveillance of exercisable goods (Decision 1152/2003/EC) replaced by Decision (EU) 2020/263 adopted in February 2020 and taking effect in March 2020;

- rules on the labelling of tyres (Regulation (EC) 1222/2009) replaced by Regulation 2020/740 adopted in June 2020 and taking effect in April 2021;

- controls on the acquisition and possession of weapons (Council Directive 91/447/EEC) replaced by Directive (EU) 2021/555 adopted and taking effect in April 2021; and

- the EU regime for the control of exports, transfer, brokering and transit of dual-use items (Regulation (EC) 428/2009) repealed by Regulation (EU) 2021/821 adopted and taking effect in May 2021 but with provision for the continued application of authorisations made under the earlier act and before 9 September 2021.

Those repealed and replaced in 2022 concern:

-

- the EU code relating to veterinary medicinal products (Directive 2001/82/EC) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/6 adopted in December 2018 and taking effect in January 2022;

- conditions governing the preparation, placing on the market and use of medicated feeding stuffs in the EU (Directive 90/167/EEC) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/4 adopted in December 2018 and taking effect January 2022;

- rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilising products (Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003) replaced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 adopted in June 2019 and taking effect in July 2022;

- regulations concerning certain categories of aid to related to the products, processing and marketing of fishery and aquaculture products (Commission Regulation (EU) No 1388/2014) replaced by Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/2473 adopted and taking effect in December 2022.

One additional act concerning plant protection (Council Directive 2000/29/EC) was repealed and replaced in December 2022 under provisions in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 which already applies under the Protocol/Windsor Framework.

The one act repealed and replaced in 2023 concerned:

-

- general arrangements for excise duty (Council Directive 2008/118/EC) – replaced by Council Directive (EU) 2020/262adopted in December 2019 and taking effect in February 2023.

In addition to the 62 repealed acts, four acts originally listed in the Annexes expired after the UK withdrew from the EU. Two of the expired acts concerned the regulation of imports from third countries affected by the Chernobyl disaster (Council Regulation (EC) 733/2008) and temporary trade measures for goods originating in Ukraine (Regulation (EU) 2017/1566). The other two expired acts made provisions related to de minimis state aid (Commission Regulation (EU) No 360/2012 and Commission Regulation (EU) No 1407/2013) and ceased to have effect at the end of 2023. In view of the expiry of these two acts, new provisions in the area of de minimis state aid were introduced under Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2831 in December 2023. These two new acts apply under Article 10 and Annex 5 of the Protocol/Windsor Framework in relation to any measures supporting trade and production of agricultural products in Northern Ireland, and to the extent that they affect trade between Northern Ireland and the EU (so including cross-border trade with Ireland).

Considering all these changes alongside those agreed to date by the EU-UK Joint Committee, the number of EU acts that apply in post-Brexit Northern Ireland has decreased since the Protocol entered into force. As of 1 January 2024, there are now 308 EU regulations, directives and decisions that apply; 30 less than when the Protocol/Windsor Framework was first agreed in October 2019 (see Table 1). The decrease is due, however, to the consolidation in a small number of replacement acts of several previous acts; it is not due to a decrease in the scope of the Protocol/Windsor Framework.

4. Amendments to applicable EU law

A third category of change involves amendments to EU acts listed in the annexes to the Protocol/Windsor Framework. These are published as discrete pieces of legislation often with ‘consolidated text’ versions of the Windsor Framework-applicable EU act following (See 6 below).

A recent example of this type of change is Commission Regulation ((EU) 2023/1490) introduced on 19 July 2023 and Commission Regulation ((EU) 2023/1545) introduced on 26 July 2023, both of which amend Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 which concerns cosmetic products. The main purpose of the first of these new acts (2023/1490) is to update lists of substances classified as carcinogenic, mutagenic, or toxic for reproduction and which are therefore prohibited under the terms of the original regulation. The main purpose of the second new act (2023/1545) is to make provision regarding requirements for the labelling of fragrance substances in cosmetic products which can cause some people to have an allergic reaction. Following a review of the EU Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) an additional 56 fragrance allergens were identified which can be allergens to people but for which there was no requirement for individual labelling under the existing Regulation ((EC) No 1223/2009). A consolidated text version of the original regulation, published in December 2023, reflects these change.

Another example of an amendment to an EU act listed in an annex to the Protocol/Windsor Framework relates to the EU generalised scheme of tariff preferences that is provided for in Regulation (EU) No 978/2012 and which was due to expire on 31 December 2023. In September 2021 the European Commission published a proposal for a new generalised tariff scheme regulation (COM/2021/579 final). Although this proposed successor regulation was supposed to enter into force on 1 January 2024, it was still in the process of being adopted. Indeed at the time of writing (March 2024), the proposal is still awaiting first reading in the European Parliament. In view of the delay, another Regulation ((EU) 2023/2663) was adopted in November 2023 to extend the application of the current generalised tariff scheme regulation to the end of 2027 or whenever the new successor regulation is formally adopted and enters into force. A consolidated text version of the amended regulation was published in November 2023; it reflects the extended deadline.

5. Changes to EU legislation implementing applicable EU law

The fourth category of change relates to legislation that implements the EU acts listed in the Annexes to the Protocol/Windsor Framework. As with repeals, replacements, expiries and amendments, this type of change is the result of normal EU legislative processes. It also follows from Article 13(3) Protocol/Windsor Framework.

To understand the significance of this fourth category it is helpful to first explain what EU ‘implementing’ or ‘delegated’ legislation is and why it exists.

Often EU directives, regulations, and decisions, such as those listed in the Annexes to the Protocol/Windsor Framework, are written in quite general terms. They are, after all, designed to apply in all EU member states. This means, however, that the original ‘parent’ act – the piece of EU legislation listed in an Annex to the Protocol/Windsor Framework – does not always set out in detail all the procedures, processes or requirements that may be necessary to implement its provisions.

So, to avoid unhelpful ambiguity or unconstructive variation in the way a new law is implemented, EU acts often provide for implementing or delegated legislation to be adopted. The difference between implementing and delegated acts reflects the process for their adoption; the purpose of both is the same, namely, to implement the parent act. Such legislation is always within the scope of a given ‘parent’ act, sets out the rules and procedures for its operationalization, is adopted after the original parent act has been passed and according to its terms.

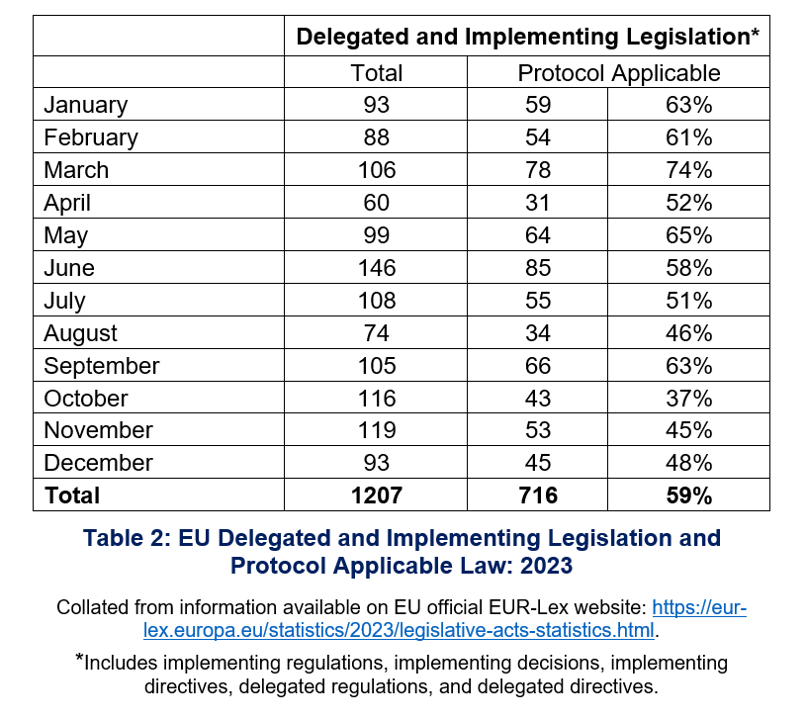

EU implementing legislation – including that applicable under the Protocol – is regularly adopted by either the Commission or the Council. In 2023, the EU adopted 1207 pieces of implementing legislation. Not all of these apply to Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Of the 1207 implementing acts adopted, 716 (representing 59%) were within the scope of the Protocol/Windsor Framework (see Table 2).

Figures for both total implementing acts adopted in 2023 and the proportion that are Protocol/Windsor Framework-applicable may seem high. It is important to note, however, that most implementing acts concern very technical, minor, and specific issues, and they remain within the scope of the original ‘parent’ act. Moreover, while all implementing acts made under ‘parent’ acts listed in the Protocol/Windsor Framework and its Annexes are applicable to Northern Ireland, not all of them are significant in terms of policy.

Figures for both total implementing acts adopted in 2023 and the proportion that are Protocol/Windsor Framework-applicable may seem high. It is important to note, however, that most implementing acts concern very technical, minor, and specific issues, and they remain within the scope of the original ‘parent’ act. Moreover, while all implementing acts made under ‘parent’ acts listed in the Protocol/Windsor Framework and its Annexes are applicable to Northern Ireland, not all of them are significant in terms of policy.

For example, implementing acts are adopted to correct errors in different language versions of an EU act: Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2911 adopted on 16 October 2023, for example, corrected the Swedish language version of Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/2146 which itself supplements Regulation (EU) 2018/848 on rules regarding organic production and labelling of organic products; similarly Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2598 adopted on 11 September 2023 corrected the Slovenian language version of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/2104 concerning the marketing standards for olive oil and which supplements Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 that concerns common organisation of markets in agricultural products. Others make provisions that are specific to a particular EU Member State or region therein: Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2023/2094, for example, was adopted on 25 September 2023 and served to extend a derogation from the application of certain EU regulations on VAT (set out in Article 75 of Council Directive 2006/112/EC) in Denmark. While all of these implementing acts make changes to EU acts that apply to Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework, neither has an ‘on-the-ground’ impact.

Some technical changes are of significance, or potential significance, in and for Northern Ireland. Indeed, in 2023, a series of implementing and delegated acts addressed Northern Ireland directly; most of these made provisions related to and reflecting the implementation of the package of measures agreed between the UK and EU in the Windsor Framework.

Examples include:

-

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/2091 of September 2023 that lays down rules for the application of Regulation (EU) 2023/1231 (see section 2) regarding the requirements for the entry of seed potatoes into Northern Ireland from Great Britain.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/2059 of September 2023 that also lays down rules for the application of Regulation (EU) 2023/1231 (see section 2) this time regarding the entry of certain ‘rest-of-the-world’ goods into Northern Ireland from Great Britain via the ‘green lane’ for retail goods.

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/1128 of March 2023 that amends Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/2446, which concerns aspects of the EU Customs Code, so as to provide for simplified customs formalities for trusted traders sending parcels into Northern Ireland from other parts of the UK.

6. The Stormont Brake for Amendments and Replacements

The above examples demonstrate the often technical and/or procedural nature of EU implementing legislation. At the same time, the potential for variation in terms of policy significance and sectoral impact in and for Northern Ireland is clear, which is partly why it is important to monitor changes arising under the Protocol/Windsor Framework, including via implementing legislation.

Moreover, in view of the potential exercise of the ‘Stormont Brake’ procedure to otherwise automatic updates to some of the EU laws that apply to Northern Ireland, tracking relevant developments is even more important following the conclusion of the Windsor Framework and the subsequent restoration of the devolved institutions in Northern Ireland in the wake of the Safeguarding the Union deal.

As part of the Windsor Framework package of measures, the UK Government provided for the establishment of a new ‘Windsor Framework Democratic Scrutiny Committee’ in the NI Assembly. Among the statutory functions of this new committee is ‘the examination and consideration of new EU acts and replacement EU acts’ as well as the ‘conduct of inquiries and publication of reports in relation to replacement EU acts’ (see SI 2024/118). As this explainer demonstrates, the tasks before the new Committee are challenging given the potential scope and complexity of relevant changes to EU law that are applicable in or relevant for Northern Ireland. For the same reason, the creation of this dedicated scrutiny body is also welcome.

7. Tracking changes to applicable EU Law – EurLex… and Consolidated Texts

Tracking change, however, is not straightforward. Adopted EU legislation is published in the Official Journal of the European Union, but determining which pieces of EU law apply to Northern Ireland, and which do not, requires detailed study and timely cross-referencing.

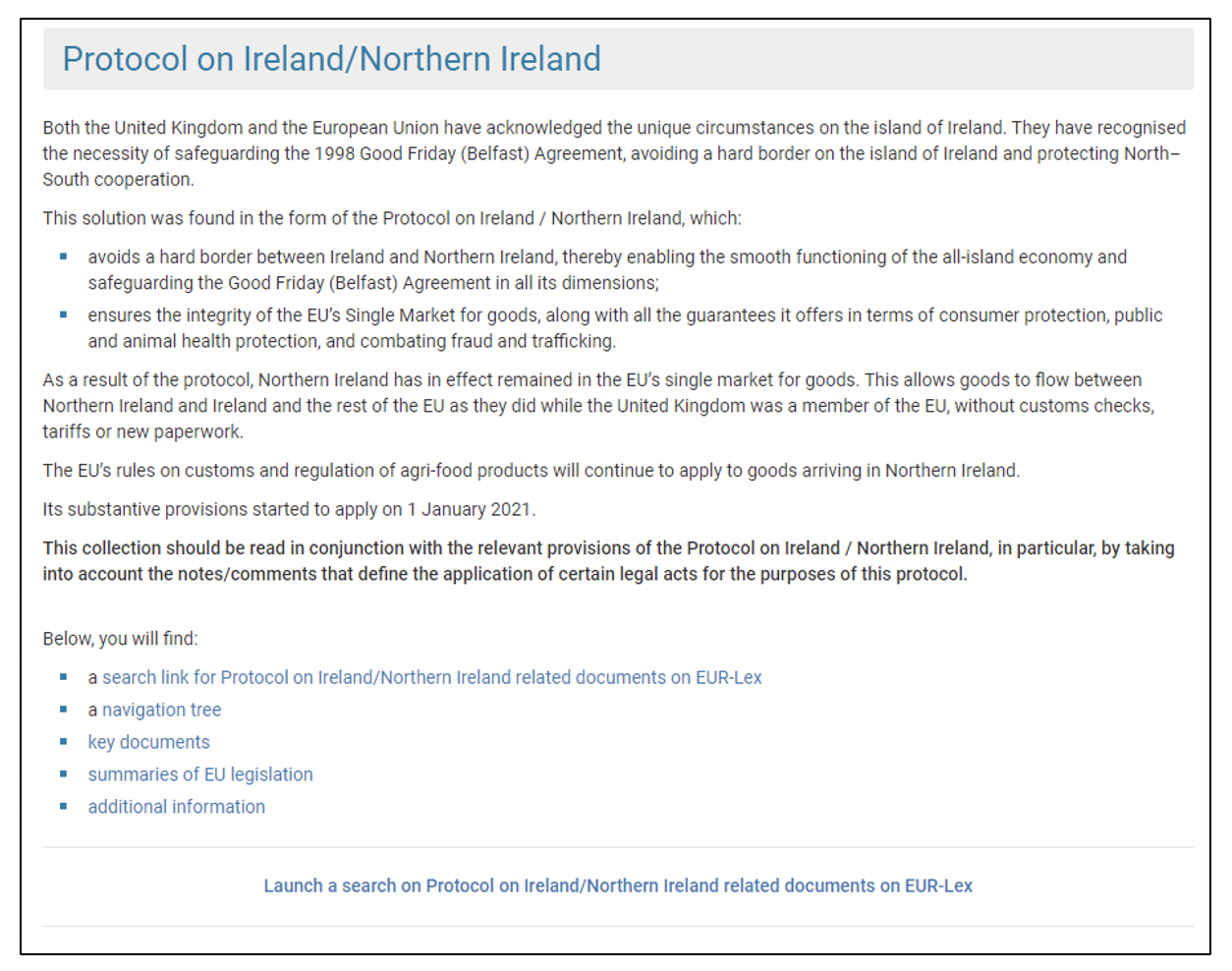

A notable development in this respect was the launch in the summer of 2022 of webpages dedicated to EU law applicable under the Protocol. Established by the European Commission as part of the EUR-Lex website, these pages list all those EU acts that apply to Northern Ireland under the Protocol/Windsor Framework and so includes ‘parent’ acts, implementing acts, repealed acts, expired acts and replacement acts. From the UK government’s perspective, the EUR-Lex website reflects ‘the EU’s view of applicability’ with the Foreign Secretary stating that its content is ‘not endorsed’ by the UK government.

EUR-Lex and the Applicable EU Law

(https://eur-lex.europa.eu/content/news/IENI.html)

Notwithstanding its ‘unilateral’ nature, as the only comprehensive official record of Protocol-applicable law, the EUR-Lex website is an important resource for anyone involved in, or affected by, the implementation of the Protocol/Windsor Framework. Calls have been made, notably by the House of Lords’ Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland Sub-Committee, for the UK government to produce its own ‘log’ or ‘audit’ of all EU legislation that applies in Northern Ireland. While they declined to commit to producing a comprehensive record of EU law that applies in Northern Ireland and changes to it, in its 2023 Windsor Framework Command Paper the UK government did commit to requiring that the Office for the Internal Market (OIM) “specifically monitor any impacts for Northern Ireland arising from relevant future regulatory changes” (para. 52). In its 2024 Safeguarding the Union Command Paper the UK government made further commitments and provisions related to monitoring the impact of Northern Ireland staying aligned with aspects of EU law, particularly on its position within the UK internal market, and established new bodies for that purpose.

A helpful tool for measuring the extent of change in EU law applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework is to track the occasional publication of ‘consolidated text’ versions of the same. When a large number of amendments have been made to a ‘parent act’ of EU law (most often via EU implementing legislation) a ‘consolidated’ version of the legal text can be published in which all relevant changes are reflected. These consolidated versions of EU acts are produced for information purposes – they are not legal texts. Nonetheless, they bring together in one place changes and can therefore provide a useful indicator of the extent to which those specific EU acts are evolving and are therefore worth monitoring.

Since 31 January 2020 when the UK left the EU consolidated text versions of 166 of those acts that apply under the Protocol/Windsor Framework have been published. Of these 147 were published after the end of the UK Transition Period on 1 January 2021, and 53 have been published in 2023.

8. Tracking changes to applicable EU law - Post-Brexit Governance NI Research Database

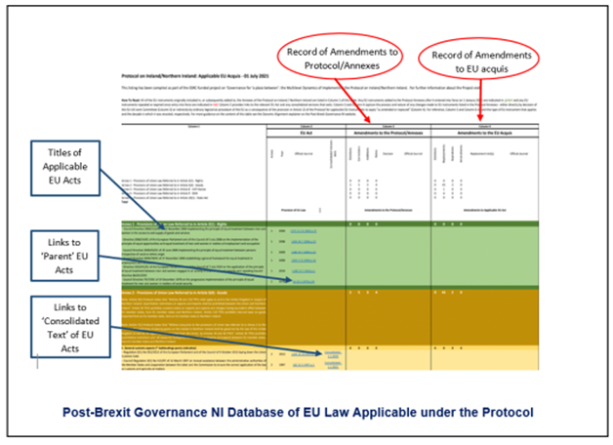

Tracking changes in EU law that apply under the Protocol/Windsor Framework is a particular focus of the four-year ESRC-funded research project Governance for ‘a place between’: the Multilevel Dynamics of Implementing the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland for which this explainer has been produced.

To this end, the project has developed a freely accessible database that provides links to each applicable EU act as well as relevant implementing acts adopted by the EU that can be found through the ‘consolidated text’ versions of the original acts; any additions, amendments, or replacements as well as the deletions and instances where, through expiry, an EU act no longer applies are also recorded. The database contains a list of all of those EU acts that apply in the UK ‘in respect of Northern Ireland’ through the Protocol/Windsor Framework as of 1 January 2024. It therefore reflects all the ‘amendments and replacements’ to applicable EU law described in this explainer.

Alongside this, the Post-Brexit Governance NI website maintains lists of relevant domestic UK laws that implement Protocol/Windsor Framework-applicable EU law where this is necessary. These include relevant Statutory Instruments passed in Westminster and Statutory Rules passed in Stormont. Examples include:

Statutory Instruments (Westminster)

- The Tobacco and Related Products (Amendment) (Northern Ireland) Regulations (SI 2023/920)

- The Equipment and Protective Systems Intended for Use in Potentially Explosive Atmospheres Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2017 (Amendment) (Northern Ireland) Regulations (SI 2023/861)

- Customs (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2022 (SI 2022/109)

- The Radio Equipment (Amendment) (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2023 (SI 2023/328)

- Value Added (Enforcement Regulated to Distance Selling and Miscellaneous Amendments) Regulations 2022 (SI 2022/226)

- Human Medicines (Amendment) (Supply to Northern Ireland) Regulations 2021 (SI 2021/1452)

- Customs (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2021 (SI 2021/1489)

Statutory Rules (Stormont)

- The Aquatic Animal Health (Amendment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2023 (SR 2023/163)

- Edible Crabs (Conservation) (Amendment) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2021 (SR 2021/336)

- Spring Traps Approval (Amendment) Order (Northern Ireland) 2021 (SR 2021/321)

- Official Controls (Plant Protection Products) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2020 (SR 2020/360).

Reflecting the nature of ‘amendments and replacements' made at EU level, the content of these implementing UK laws tends to be technical and specific.

Conclusion: A dynamic democratic challenge

What is clear from this explainer is that implementation of the Protocol/Windsor Framework and the process of dynamic regulatory alignment involve extensive legislative complexity.

Since the terms of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU were agreed in October 2019, the EU acquis that applies under the Protocol/Windsor Framework has changed. To date, however, the majority of the most substantive ‘amendments and replacements’ enact changes agreed while the UK was still part of the EU. This reflects the generally slow pace of EU legislative processes and the fact that the EU acquis that applies in post-Brexit Northern Ireland – primarily concerning trade in goods – is relatively stable. However, more recent ‘amendments and replacements’ reflect post-Brexit changes to EU law and more will follow.

As the UK diverges from what was EU law and is now assimilated EU law, the implications of Northern Ireland’s dynamic regulatory alignment can be expected to become more evident and more significant in respect to policy development and implementation. As the Windsor Framework focuses primarily on easing checks and controls on GB-NI goods movements, EU acts applicable under the Protocol/Windsor Framework continue to apply to goods being produced in Northern Ireland; they also apply to GB goods not entering Northern Ireland through the ‘UK Internal Market Lane’. Dynamic regulatory alignment therefore remains real in and for Northern Ireland.

This returns us to the challenge of managing the practical effects of dynamic regulatory alignment alongside ensuring democratic accountability and legislative scrutiny in Northern Ireland. These challenges follow from both the novelty of the Protocol/Windsor Framework’s provisions and the degree of transparency that has so far surrounded the activities of the three joint UK-EU bodies set up to oversee the implementation of the Protocol and now the Windsor Framework: the EU-UK Joint Committee, the Specialised Committee on the Implementation of the Windsor Framework, and the Joint Consultative Working Group.

To address these, at least in part, the Windsor Framework included provisions and commitments regarding NI stakeholder engagement in the implementation of the Protocol. For example, in Declaration 2/2023, the EU-UK Joint Committee agreed that relevant meetings of the Specialised Committee’s (new) Special Body on Goods and the Joint Consultative Working Group (new) sub-groups – both composed of UK and EU experts – could invite representatives from business and civic society stakeholders to attend. Additionally, in a statement on ‘enhanced engagement with Northern Ireland stakeholders’ the European Commission committed to provide: annual presentations of upcoming EU policy initiatives and legislative proposals relevant to Northern Ireland; specific information sessions on new EU initiatives if/as requested by stakeholders; relevant public consultations and/or involvement of Northern Ireland stakeholders in targeted consultations for specific case; and dedicated overviews of Northern Ireland stakeholders input into consultations.

If operationalised effectively, the Windsor Framework’s agreed new avenues for stakeholder engagement, alongside the new Safeguarding the Union provisions for better internal UK monitoring of the implications of NI alignment on its place in the domestic market, could collectively address concerns regarding the unique arrangements that apply in Northern Ireland, particularly as regards the interests of its representatives being heard in related processes. If stakeholder engagement does not deliver, MLAs may seek to see the Stormont Brake activated. Regardless of and notwithstanding the more recently established mechanisms and bodies, the still overriding point for Northern Ireland is that regulatory alignment is and remains a central element of the Protocol/Windsor Framework, and so its multiple dimensions need to be monitored and understood.

March 2024

Dr. Lisa Claire Whitten is Research Fellow on the Governance for ‘a place between’: the multilevel dynamics of implementing the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland at Queen's University Belfast. She can be contacted via: l.whitten@qub.ac.uk.

Download a copy of this Explainer here