Student Research: Investigating Contamination in Urban Soil and Vegetables

Urban community gardens and allotments provide many social and environmental benefits, but how safe is produce grown in urban soils? Postgraduate student Jennifer Newell describes her research into urban agroecology.

I’m a research student working with the UPSURGE project (funded by European Union Horizon 2020) to investigate the development of a community garden on the Lower Botanic Gardens in South Belfast, as a nature-based solution to counter urban social, economic, and environmental issues. With a legacy of industrial contaminants in the local soils, it is important to determine whether food crops grown onsite will pose any human health risks.

My research explores the potential risks associated with consuming vegetables grown in the site soils, and also considers ways of reducing any risks using biochar (charred organic matter) to adsorb soil contaminants.

Vegetable polytunnel experiment

In February 2023, I constructed a polytunnel (2x3m) in a sunny corner of the David Keir Building quad to house a vegetable pot experiment. Within this structure, I set out 36 pots, each containing around 10 kg of soil from the UPSURGE site located in the Lower Botanic Gardens. The soil was then either amended with 0.5 kg (5%) biochar, or left unamended and used as a control.

The polytunnel in the David Keir Building quad

The pots were then planted with three commonly consumed vegetables: ‘Salad bowl’ lettuce, ‘Chantenay Red Cored’ carrots, and a hard-neck garlic variety called ‘Eden Rose’. These three planted vegetables represented different edible parts of a vegetable (the leaf, root, and stem, respectively). They also typically present different growing periods (2 months for lettuce, 4 months for carrot, and 8 months for garlic).

The seeds and garlic cloves were bought locally in Belfast, so I knew they would be suitable for growing in the area. The initial phase involved planting the seeds and cloves, and a preliminary watering of all the pots. The following few weeks required weekly watering, measuring soil temperature and humidity, and pest monitoring as I waited for the first tiny green shoots to appear.

Planting the garlic

Challenges and risks

The frosty weather over spring meant I had to add an extra layer of insulation in the polytunnel to protect the new seedlings. Though, only a few weeks later, the beautiful sunshine made the polytunnel conditions too warm for the cool-weather carrots, and the doors of the polytunnel were opened to encourage a cooling breeze. I also found some carrot-loving click beetle larvae and snail pests which were a bit of a challenge to control. Ultimately though, most pots have been successful in producing some crops from the Lower Botanic soils.

Vegetable shoots in early-April (L-R: garlic, lettuce, carrot)

Lab work

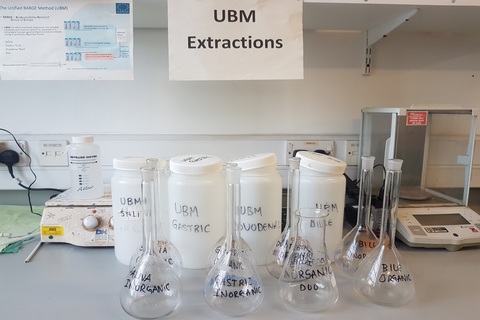

Up in the lab overlooking my vegetable polytunnel, I have an artificial laboratory-based human digestive system comprised of saliva, gastric, duodenal, and bile fluid phases, based on the BARGE Unified Bioaccessibility Method (UBM). By passing soils or vegetables through this digestive system and then analysing the final metal contaminant concentrations, I can determine the total amount of contaminant that is available for absorption from the gut. From this, I can then assess comparable human ingestion risks from my control and biochar pots.

In March, I passed the pre-vegetable pot soils through this system, and, encouragingly, it showed that biochar has some potential for reducing lead risks when ingesting soil dust particles.

Some of the equipment for my lab-based human digestive system

The first crop

In the polytunnel, the first crop to seed and mature was the frilly ‘Salad bowl’ lettuce in late May. I had already noticed a clear difference in yield between lettuce grown in biochar and control pots (organic biochar has many nutrients!). So regardless of the impact on contaminant remediation, biochar has already indicated it may be useful to boost food production in clean commercial farms instead.

Lettuce ready for harvest in May

Food testing

As soon as the lettuce was deemed ready to harvest, I removed the edible lettuce leaves from each pot and oven-dried the foliage for 24 hours to remove all the moisture, and then ground the brittle leaves to a powder for testing. Similarly, I dried and sieved the post-lettuce soils, and then passed both lettuce and soil powders independently through the UBM system. The lettuce results are yet to be analysed, and there are still further tests to be done on the carrots and garlic later in year.

Harvesting the lettuce

Ultimately though I am optimistic that these tests will provide more information on the potential metal ingestion risks in urban soils, and provide some evidence of the remediation benefits of biochar to support nature-based solutions.

Acknowledgements: This project is supported by the European Union Horizon 2020 UPSURGE project (Grant agreement No.: 101003818).

Jennifer NewellCivil Engineering | Postgraduate Student | EnglandI’m Jennifer, a second-year postgraduate research student in the School of Natural and Built Environment. I have a passion for environmental sciences and have dedicated much of my academic life to exploring the best ways we can protect and enhance our natural world. I am most often found wearing wellington boots and tending vegetable plots, tracking insects through the Lagan meadows, or admiring the view atop the Belfast hills. |

|