Northern Ireland has a long history of immigration and diversity. And of racism.

Dr Jack Crangle discusses recent anti-immigration disorder in Northern Ireland, and places it in historical context.

Earlier this month, the County Antrim town of Ballymena – along with other parts of Northern Ireland – witnessed widespread rioting driven by racism and xenophobia. The disorder began after two teenage boys appeared in court accused of sexually assaulting a teenage girl. Tension boiled over when it emerged that the two boys were Romanian speakers and their alleged victim was a white ‘local’. What began as a supposedly peaceful anti-immigration protest soon descended into several nights of violence, with houses, businesses, cars and even a leisure centre being set on fire and dozens of families driven from their homes.

Shocking as this month’s disorder was, the issues underpinning it were far from new. Contrary to popular knowledge, Northern Ireland has a long history of immigration from across the world. It also has a long history of xenophobia and racism. In 2023, I published the first ever book on this hidden history of Northern Irish immigration and diversity, charting the rise of various migrant communities, the experiences that they had and the welcome (or otherwise) that they received.

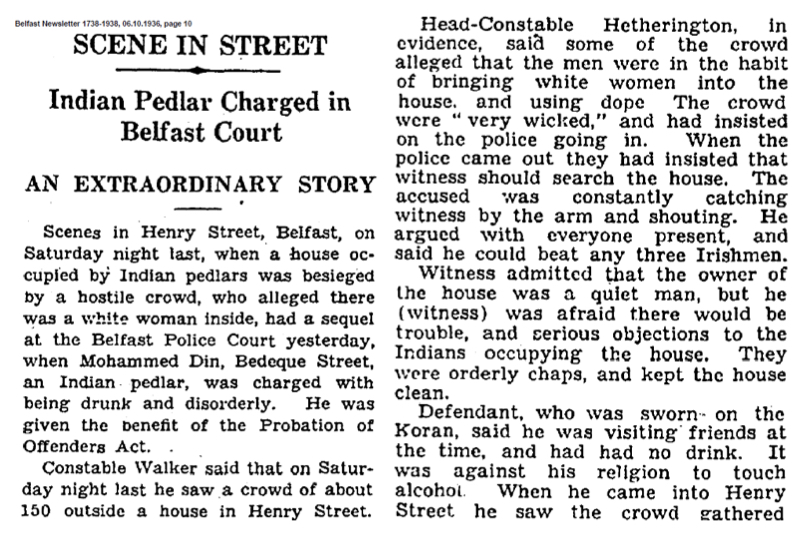

The book chronicles the people and communities who moved to Northern Ireland over the past century, even during the darkest years of the Troubles. By the mid-1970s, despite a raging internal conflict, thousands of Chinese and South Asian migrants lived across the region. Muslims have lived in Northern Ireland since the late 1920s. Archived news items (such as in the excerpts pictured below) provide insight. For instance, 1936 witnessed an incident with chilling echoes of the Ballymena riots when one of Northern Ireland’s first Muslim immigrants, Mohammed Din, has his house besieged by an angry mob of 150 people after he allegedly slept with a white woman. On that occasion, the police intervened, the crowd dispersed, and an uninjured Din was charged with disorderly conduct.

Above: Excerpts from the Belfast News Letter, 6 October 1936 (see below for transcription).

The book is replete with accounts of racist violence, verbal abuse, slurs, xenophobic stereotypes and racist ‘jokes’ dating back over a century. Tragically, some of these incidents resulted in murder, such as the killings of Simon Tang in 1996 and Brij Sharma in 2004.

Until relatively recently, racism in Northern Ireland was never believed to be a social problem. Throughout the Troubles, many people consoled themselves by believing that, for all its problems, Northern Ireland was remarkably free from racial prejudice. In 1964, a Northern Ireland Labour Party politician declared that ‘coloured people from any part of the world will get a greater welcome in this small country than they will get anywhere else’. Such was this belief in racial tolerance that, when the UK government passed successive laws outlawing racial discrimination in the 1960s and 1970s, Northern Ireland was given an exemption on the grounds that racism ‘did not exist’ there. Racial discrimination was only outlawed in Northern Ireland in 1998.

The reasons for this complacency were twofold. Firstly, because immigration numbers were so small, most people assumed that racism was not an issue. Unlike in Great Britain, where Black and Asian migrants numbered hundreds of thousands, Northern Ireland did not witness visible, widespread racist violence such as the anti-Black Notting Hill Riots in London in 1958. Nor did Ulster politics produce any noteworthy far-right political movements such as the National Front. Racism in Northern Ireland was often more hidden and subtle, making it easier to deny.

The other excuse used to explain Northern Ireland’s supposed lack of racism relates to the region’s sectarian divide. Some commentators and researchers believed, especially during the Troubles, that people in Northern Ireland were so preoccupied with fighting one another to bother with racism. The book puts paid to this notion. Although immigrant families were granted some degree of shelter from the conflict due to their sectarian ‘neutrality’, they were inevitably affected by Northern Ireland’s atmosphere of suspicion and hostility.

Sometimes, sectarianism and racism combined to produce an especially potent blend of hatred. One of the book’s interviewees, a second-generation Chinese man, was walking through a loyalist area of Belfast during the 1980s wearing his local Catholic school uniform when he was beaten up by a gang of youths. During the ambush, his attackers shouted both racist and sectarian slurs. Identifiable as both Chinese and Catholic, this schoolboy was profiled as doubly objectional and therefore subjected to two layers of abuse.

Far from shielding people of colour, Northern Ireland’s culture of sectarianism could structure, reinforce and exacerbate racism. We are now seeing the legacy of this in places such as Ballymena. Sectarianism is predicated on fear, mistrust and hostility towards an external ‘other’. Throughout Northern Ireland’s history, especially in traditional working-class area, this antipathy has been directed towards the ‘other side’: Catholic-nationalist or Protestant-unionist. As immigration to Northern Ireland has increased, and its minority-ethnic population has grown, such suspicion is increasingly directed towards a new ‘other’.

The June 2025 riots were not the first of their kind, nor were they specific to Northern Ireland. Similar disturbances were witnessed in Dublin in November 2023 and across the UK (including in Belfast) in August 2024. Anti-migrant sentiment is growing across the western world, partly driven by social media. But the disorder in Northern Ireland has also been shaped by the region’s legacy of geographical segregation, where flags demarcate the territory of competing groups and ‘outsiders’ face aggression.

Northern Ireland is now far more than a society of only ‘two communities’: Catholic and Protestant. It is a diverse society of multiple faiths, ethnicities and nationalities. This demographic change can be harnessed for good, to move beyond the tired, parochial and oppositional discourse of the conflict and envisage a new pluralistic Northern Ireland. Sadly, an ‘us versus them’ mentality persists in in many areas, especially those that feel left behind by globalisation and the peace process. This anger is increasingly being directed towards migrants, Muslims, refugees and asylum seekers, some of Northern Irish society’s most vulnerable communities.

----

Transcription from Belfast Newsletter, 06.10.1936

Scene in Street.

Indian Pedlar Charged in Belfast Court

An Extraordinary Story

Scenes in Henry Street, Belfast, on Saturday night last, when a house occupied by Indian pedlars was besieged by a hostile crowd, who alleged there was a white woman inside, had a sequel at the Belfast Police Court yesterday, when Mohammed Din, Bedeque Street, an Indian pedlar, was charged with being drunk and disorderly. He was given the benefit of the Probation of Offenders Act.

Constable Walker said that on Saturday night last he saw a crowd of about 150 outside a house in Henry Street.

Head-Constable Heatherington, in evidence, said some of the crowd alleged that the men were in the habit of bringing white women into the house, and using dope. The crowd were “very wicked,” and had insisted on the police going in. When the police came out they had insisted that witness should search the house. The accused was constantly catching witness by the arm and shouting. He argued with everyone present, and said he could beat any three Irishmen.

Witness admitted that the owner of the house was a quiet man, but he (witness) was afraid there would be trouble, and serious objections to the Indians occupying the house. They were orderly chaps, and kept the house clean.

Defendant, who was sworn on the Koran, said he was visiting friends at the time, and had had no drink. It was against his religion to touch alcohol. When he came into Henry Street he saw the crowd gathered.

----

ENDS