- Can Animals Catch and Spread Coronavirus?

- Queen's University launches Covid-19 Research Roundtable video series

- Queen’s rising to the COVID-19 challenge: The importance of simulation in healthcare

- How much of the coronavirus does it take to make you sick? The science, explained by Dr Connor Bamford

- TEDxQueensUniversityBelfast: Adapt and Change

- Prepare to sleep and sleep to be prepared.

- Supporting Children in Isolation

- Supporting Pets During Lockdown

- Immunology and COVID-19: Shaping a better world podcast

- Global trading: the good, the bad and the essential

- Global food supply chains in times of pandemic

- The impact of lockdown on isolation and loneliness

- Cancer Care in the Era of COVID-19

- ‘Giant’ of astronomy to host live school lessons

- How the pandemic is further alienating the disabled community

- COVID-19 and Older People: Shaping a better world podcast

- Engaging your child to learn during lockdown

- Stay well: Our expert guide to wellbeing during lockdown

- Working parents are feeling the strain of lockdown

- How is coronavirus affecting animals?

- The Coronavirus Act: Where it Falls Short

- Economic rebirth after COVID-19

- Coronavirus and the new appreciation of teachers

- ‘Make room for fun’: home-schooling for parents

- Why a collaborative research culture is needed to address the COVID-19 challenge

- COVID-19: Don’t bank on a rapid economic recovery

- Explained: the importance of behavioural responses when implementing a lockdown

- COVID-19: Curbing a loneliness epidemic

- How soap kills the COVID-19 virus

- An expert’s guide to working from home

- How to exercise safely during a pandemic

- Five tricks your mind might play on you during the COVID-19 crisis

COVID-19: Don’t bank on a rapid economic recovery

Hopes that government-administered CPR can jolt the economy back to life after the coronavirus recession are too optimistic, says John Turner, a Professor of Finance and Financial History at Queen's Management School.

With the UK government pledging to do ‘whatever it takes’ to ease the financial fallout of lockdown restrictions, it is hoped that the sudden economic free-fall triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic can be swiftly rectified.

However, Professor John Turner, a financial expert from Queen’s Management School, fears the government’s stimulus package - providing financial support for employees and businesses – will only act as a temporary duct tape over inevitable and dire economic consequences in the future. Far from roaring back to life, he suggests the economy is more likely to limp through a long and painful recovery process with the after-effects lingering for years to come. Here, he highlights nine issues we should be concerned about.

1. Consumers will remain cautious

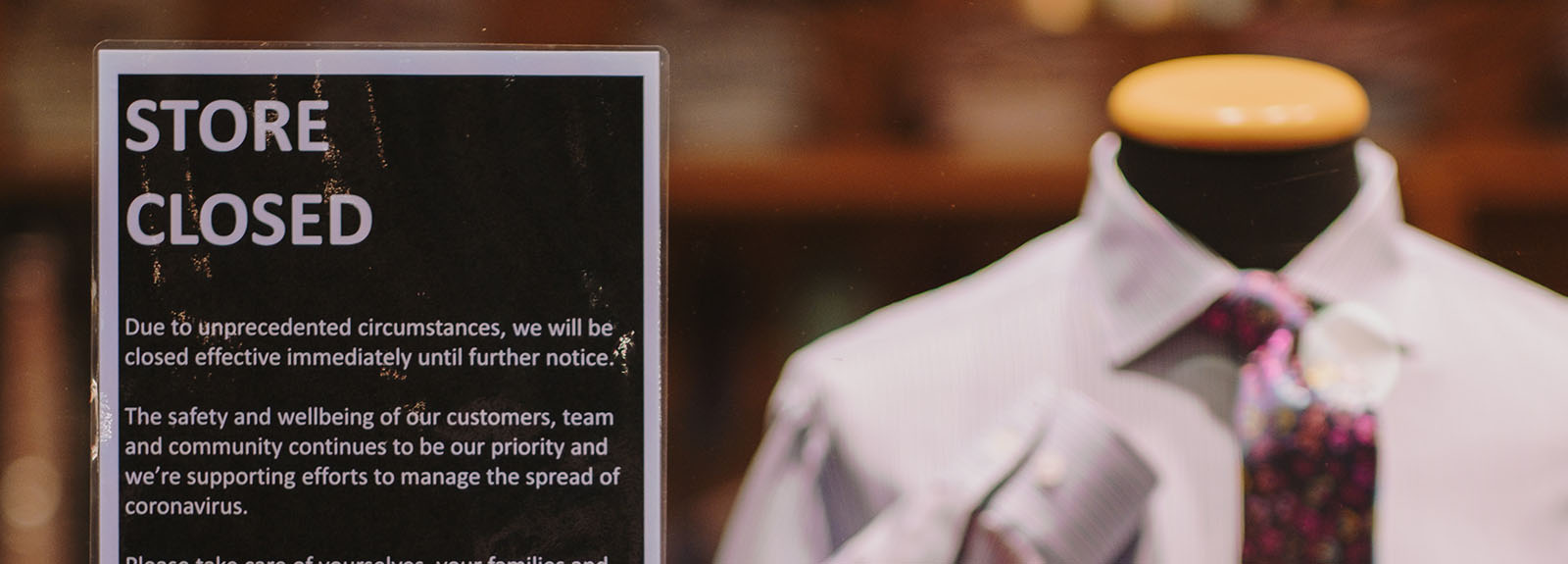

Once the lockdown is lifted and businesses and shops re-open, one lingering effect will be that consumers will remain cautious about spending, says Professor Turner.

“A lot of people are talking about a V-shaped recovery,” he says. “Imagine we’ve been playing a piece of music and we’ve pressed pause for a few weeks and the dancing stops. And suddenly when we press play again, the dancing starts where it left off and everything will be back to normal in the economy. That’s a very optimistic view in my eyes because people are not all of a sudden going to go out and spend money again. They are going to be more cautious – some will have lost their jobs, and others, anticipating higher taxes and rising inflation as a result of government bail outs, will cut back on their consumption. If people aren’t going to spend money, that is going to dampen the economy for a long, long time to come.”

2. The economy wasn’t in good shape to start with

While an economy that was healthy before a sudden dip caused by the outbreak could potentially rebound quickly, that is not the case for the UK, and for most of western Europe, notes Professor Turner.

“My concern is that the governments and banks have used all their ammunition fighting the last crisis,” says Professor Turner. “It’s like they are the fire and rescue service and they have sprayed all their foam and they have used all their equipment and now, for this crisis, they don’t have a lot of room to manoeuvre because interest rates were super low to start with.

“Governments and central banks are now raising a lot of debt to help keep businesses going and to help pay employees’ salaries for a short period of time. That is all going to have to be paid back. We are talking about large numbers and a lot of debt and it takes a lot of time and a lot of pain to repay debt.”

He adds, “I don’t think we are going to have this sharp rebound that people hope for.”

3. We’ve seen the largest stock market drop since 1987

The scale of the economic plunge is unprecedented, says Professor Turner. “In the first quarter of 2020, we’ve witnessed the largest three-month drop in the UK stock market since 1987,” he says. “The market is down by about 25% since the start of the year.”

While the sharpest plunge was in early March at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis in the UK, with the market down by a third, the worst is not necessarily behind us.

The FTSE 100 has slipped, with airlines and oil companies among the hardest hit, says Professor Turner, who adds that shares in the leisure industry and banks have also tumbled.

“The FTSE 100 has got major airlines in it,” he explains. “EasyJet share prices have dropped by about 75% per cent and the same is true for International Airlines Group, the parent company of British Airways - its share price is also down substantially,” he says. “Oil companies have taken a major hit due to oil prices tumbling from $70 a barrel to $20 a barrel in the space of a few weeks.”

4. The potential scale of the crash is bigger than in 2008

While the 2008 financial crash was an internal crisis affecting only certain countries, the potential financial fall-out from COVID-19 looks to be more far-reaching.

“Unlike in 2008, this crisis has come from outside. It’s what economists call an exogenous shock,” says Professor Turner.

“It’s also different in its potential scale. Look, for example, at the unemployment numbers that were announced in the United States last week: they added 3 million people to the unemployment list in the matter of few weeks. In China, the latest forecasts are predicting that their economy might grow by one or two per cent, which is like a recession for a country like China. China’s economic growth since 1978 has averaged over 9 per cent per year.”

5. GDP will fall further than in the 1920s

Gross domestic product (GDP), a concept used to measure the size of a country’s economy, is set to fall further than it has since the early 1920s.

“The fall in GDP potentially will be larger than in the 2008 crash,” says Professor Turner. “The 2008 crash resulted in a 4.5% fall in GDP in the UK. Some projections are putting the GDP fall at closer to 10%.”

6. Pensions will be impacted

While billionaires will see large percentages skimmed off their net worth, the real consequences of the COVID-19 stock-market crash will be felt by the average person. “It is going to directly impact your pension. Most pensions are largely invested in the stock market,” explains Professor Turner. “In the midst of all this, prices of government bonds have also been dropping and interest rates are virtually zero. That’s a concern because pension companies also invest very heavily in government bonds.”

7. Many businesses were already on their knees

While the government encourages banks to lend to small businesses to help them ride the COVID-19 storm, Professor Turner notes that many businesses may already have been in trouble.

“Some of these businesses may have been pretty close to the wall anyway and may not have had a great cash flow and they will end up going to the wall and those jobs won’t be there,” he says.

“The airline industry is going to be decimated after this. Airlines are all going to need government bail outs; think of all the people who work at airports. Those jobs are not going to come back quickly. All of this creates problems for graduates coming out into the job market in the next few years, it is going to be tough job market for a few years.”

8. There is pressure on exchange rates

With investors and businesses seeking out a safe haven in dollars – the world’s reserve currency – the US Federal Reserve have had to broaden access to dollars.

“As the pandemic spread, everyone was looking for dollars because the dollar is a safe haven. The US Federal Reserve opened up swap lines to give other central banks bucketloads of dollars to distribute to whoever needs it in their economy,” explains Professor Turner.

Adding, “The pound dropped to £1.13 against the dollar. It hadn’t been down that level for nearly forty years. Now, it has rebounded a bit because the FED opened up the swap lines.”

9. Firms can’t repay debt

The Bank of England have requested that all banks in the UK stop paying dividends; a sign that the banking industry is being prepared for the worst, says Professor Turner.

“Essentially this is to store up all that money, rather than pay it out to shareholders. They are making sure it is there to cover the banks' losses when companies and small business fail,” says Professor Turner.

He adds, “Firms have borrowed very heavily coming into this crisis because debt was so cheap and there will now be a problem with those firms being able to repay that debt. If this crisis goes on longer than anticipated, we could see bank rescues and bank nationalisations having to take place – that, however, is the worst-case scenario.”