Lost Revolution: The Abbey Theatre & 1916

"Did that play of mine send out/Certain men the English shot" – William Butler Yeats, ‘The Man and the Echo’ (1938)

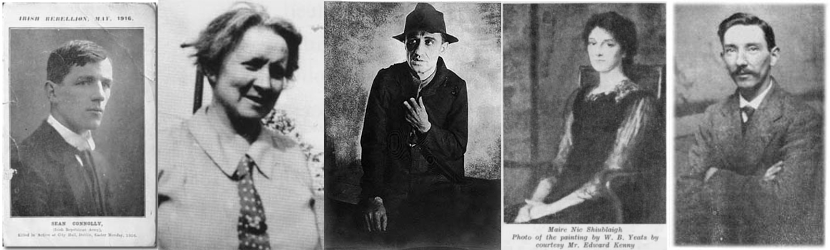

The story of the Abbey’s role in Ireland’s revolution is well-known: through powerful dramas like Cathleen ní Houlihan, the national theatre established by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory played a leading role in the cultural nationalist revival, politicising a generation of revolutionaries. When Yeats asked ‘Did that play of mine send out/Certain men the English shot?’, he was thinking of the Abbey actor, Sean Connolly, the first rebel fatality of 1916. Following independence, the Abbey became the first theatre in the world to receive a state grant in acknowledgement of its contribution to the winning of Irish freedom.

This film explores the individual lives of the Abbey’s 1916 rebels to tell a more complicated story about the tensions between the Abbey theatre and Irish nationalism, the complex relationship between culture and revolution, and the gulf between the radical aspirations of the Abbey’s rebels and the conservative outcome of their revolution.

It focuses on the story of the following individuals:

- Máire nic Shiubhlaigh, the Abbey’s first leading lady (the first stage actor to perform under a Gaelic stage name) who left the Abbey as a result of her radicalism.

- Helena Molony, a socialist, feminist republican (the first female political prisoner of her generation) who played a leading role in the lock-out, Citizen Army, and rebellion.

- Peadar Kearney, Fenian, Gaelic Leaguer, and author of the national anthem, who broke with the Abbey to fight in the rebellion.

- Arthur Shields, a Protestant socialist who became a Hollywood film star.

- Sean Connolly, who died after leading the attack on Dublin Castle.

Their lives tell the story of a lost revolution. By contrasting the radical, socialist, feminist, and intellectual impulses of republicanism before the Rising with the conservative, Catholic ethos that emerged after independence, it tells a story of the 1916 Rising that is relevant for our times, a story of missed opportunities and alternative futures, and the failure to achieve the radical goals of the Easter Proclamation.

"If Yeats had saved his pencil-lead/would certain men have stayed in bed? For history’s a twisted root with art its small translucent fruit/and never the other way round." – Paul Muldoon, ‘7, Middagh Street’ (1987)