History on TV – a good thing?

Angela Graham, Development Producer on the TV documentary series The Story of Wales considers the ingredients for a happy relationship between historians and television.

Television documentary loves history but how true is the reverse, among professional historians? At one extreme, television is seen as going for the good story at the expense of the facts or leaving out nuances that would modulate the reception of facts in important ways. From this perspective, television is a broad-brush medium and therefore dangerous for history because ‘broad-brush’ might shade into ‘superficial’. Television history, at its worst, it is thought, peddles platitudes, confirms prejudices and encourages lazy, sentimental accounts of the past in which today’s perceptions and preoccupations are allowed to dictate the interpretation of yesterday’s events. It is not truth which is pursued but the ratings.

Accounts of anything differ according to the point of view of the raconteur. Historians are keen to remind us of this. How can television cope with the complexities of the past? Is the research behind television history shallow in comparison to academic research? Some historians forswear TV completely. Queen’s University’s School of History and Anthropology is not going in that direction.

Academic unease about history on television can be ameliorated by better mutual understanding of the respective worlds and expertise of academia and the media. I’d like to consider the making of The Story of Wales to identify where the aims of academics and producers of TV history overlap and where they could benefit from some mutual adjustment. This understanding leads to realistic mutual expectations.

The genesis of The Story of Wales

BBC Wales, in May 2010, invited proposals for a series on Welsh history. Green Bay Media an independent production company in Cardiff, won the commission. It went for a narrative rather than a disputational format but one that allowed for the presentation of conflicting interpretations. This generation needs a chance to encounter the narrative as there are few opportunities to do so.

The TV history of a nation is a significant cultural event. It aims to hold a mirror up that offers an image which is true but which does not claim to contain all that one could possibly want to know. Television documentary offers to historians its expertise in communicating to a large and diverse audience. Ideally, the programme outcome is forged from the best of both disciplines.

Expertise Good television history broadens the spread of historical understanding and it results when broadcasters and historians respect each other’s expertise. Television research, for instance, is a different beast to historical research. It runs to deadlines whose imminence can surprise historians. A good TV researcher excels at the intelligent and speedy consumption of large amounts of information, is adept at synthesising and at spotting gaps and recognises who has the gift of easy communication and who will need help to bring out their treasures. The TV researcher must also form a sense of the debates within a discipline and also of its internal politics. The good TV researcher seeks to serve the truth, as does a good historian, so s/he is humble, knowing that s/he is never the expert on anything, except – and it’s an important ‘except’ – in knowing how to shape the expertise of others for the medium in partnership with the producer.

Good television history broadens the spread of historical understanding and it results when broadcasters and historians respect each other’s expertise. Television research, for instance, is a different beast to historical research. It runs to deadlines whose imminence can surprise historians. A good TV researcher excels at the intelligent and speedy consumption of large amounts of information, is adept at synthesising and at spotting gaps and recognises who has the gift of easy communication and who will need help to bring out their treasures. The TV researcher must also form a sense of the debates within a discipline and also of its internal politics. The good TV researcher seeks to serve the truth, as does a good historian, so s/he is humble, knowing that s/he is never the expert on anything, except – and it’s an important ‘except’ – in knowing how to shape the expertise of others for the medium in partnership with the producer.

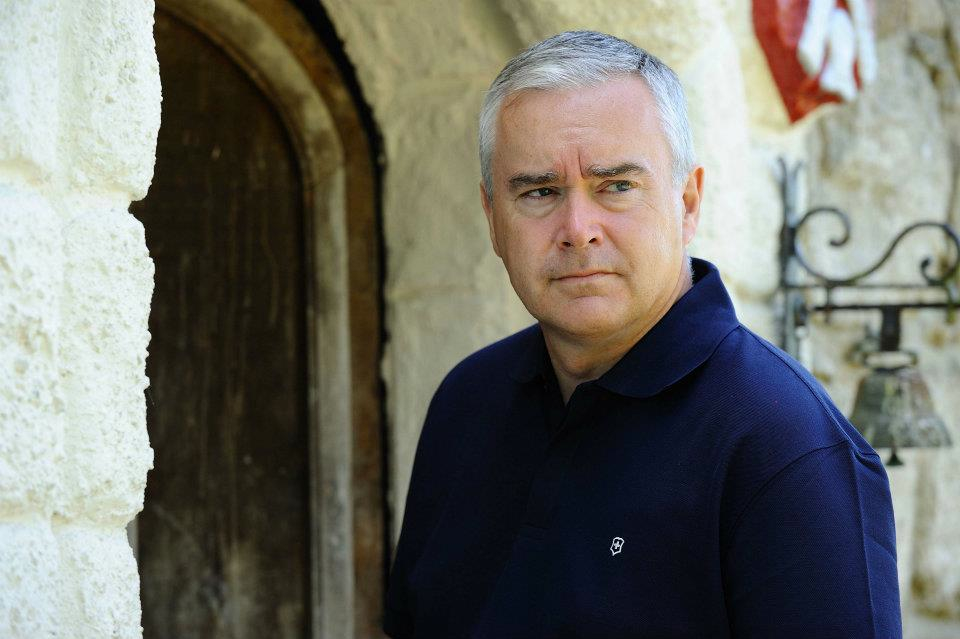

The Story of Wales did not have an advisory panel of historians who exercised editorial control. Editorial control is the task of the producers. Huw Edwards, the BBC’s pre-eminent newscaster, was chosen as presenter because he has the necessary skills, experience and presence to carry a project of this complexity. Clearly, a production company must behave so as to deserve the trust of academics in this kind of partnership.

A BBC ‘hour’ is almost 60 minutes (unlike some other channels where programme content is as little as 42 minutes) yet even six hours is not long to deal with 30,000 years of history which was the task we set ourselves. There must be selection. Within each hour the content is designed to have an overarching story arc from start to end but, within that, several smaller narrative arcs so that the material is graspable. The episode endings are carefully gauged. They are not cliff-hangers but they are not random. They aim to poise at a point of change, with some natural looking-back and some inherent forward momentum perceptible. A great deal of dialogue between producers and historians is called for in reaching these decisions.

Historians and the series

More than 50 historians were consulted (alongside the consultation of the published work of others) and 33 appeared onscreen. It was still not enough historians on screen for some but this is to misunderstand how experts can contribute to a series. If the pre-filming research and preparation has been as good as it should be then the script will carry the input of experts confidently; they do not have to be onscreen extensively. The over-use of expert contributions can be a sign that the programme-makers have not mastered the facts and have played safe by too great a reliance on ‘getting the experts to say it’ in chunks of recorded interviews. A programme is an artefact which has to be assembled carefully so as to maintain a rhythm and pace that makes it a pleasure to watch. When deployment of interviewees is skilful the term ‘talking-head’ never enters one’s mind because every onscreen contribution seems to occur just where it is needed and each contributor is helped to give his or her best.

Institutional Partners and Outreach

Television documentary is very good indeed at stimulating interest and acting as a door into further learning. BBC Wales collaborated with three ‘National Partners’: the Museums of Wales, the National Library of Wales and CADW (the Historic Environment Service). These, as well as providing advice and expertise, gave access to locations and objects. In addition the National Trust and the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historic Monuments provided similar services. The Open University was Co-Commissioning Body with the BBC. The O.U. assembled a panel of academic consultants who gave detailed advice and checked the scripts and images used. The O.U. produced a free booklet based on the series (advertised after each transmission) and integrated the programmes in its educational strategy. All of these organisations have assiduously exploited the series’ reach in their own constituency, making it easy for viewers to follow on from the programmes.

In addition the BBC designed a multi-media outreach including a book of the series, Facebook page, blogs, other printed material and a DVD. Two radio series, in Welsh and English, took thematic approaches to the series and provided an opportunity for directly oppositional interpretations of material. There were two ‘Making-of’ programmes which included topics not in the main series, a post-series studio discussion, additional material in Welsh and a package for Schools.

Audience Response

The 6 hours went out in February and March 2012 on BBC 1 Wales at 9pm. The Audience Appreciation Rating showed how much it was enjoyed: it attracted the highest AAR (92%) for any BBC programme on any BBC channel since January 2011 to transmission (Spring 2012) apart from ‘Frozen Planet’.

The audience share was 28% which is exceptionally high. It suggests that one in every 10 people in Wales saw the programmes. The response on Twitter and other social media was extraordinary. Very often people commented, simply, ‘I never knew!’ Why, it must be asked, was so much of their history a book previously closed to them?

TV History - cumulative or one-off?

The producer has to win each commission; there is no automatic next series. So, in the case of history on television, is one building an audience from one level of complexity to another with each programme or series or is one always starting from scratch with each TV project? Is history on television largely a one-off experience for the viewers or a cumulative experience? Which should it be? Can it be both? To some extent the answer to this is in the hands of commissioning editors but as producers we hold to a conviction that we can trust the intelligence of the audience. There may be things the audience does not know but if given an opportunity to know they will be able to understand. Historians could make a great contribution to history on TV by developing relationships with commissioning editors and regarding programme-makers as potential partners.

Academia/Media encounters

We should see more encounters between broadcasters and academics. The day before the Reframing History conference the School of History and Anthropology at Queen’s ran a meeting between staff, postgraduate researchers and TV producers. We also heard of the department’s success in gaining AHRC funding for the production of a taster for a documentary, another ‘first’, news of which I have been holding up as an example to Welsh academics and programme-makers.

These are welcome steps in developing historians who understand how to work with television. They are likely to go on to make excellent use of a range of media. There are skills to be learned and there is a significant difference between being an academic who knows how to do a news sound bite and one who knows how to participate well in the production of a documentary. Historians who have been abused by unscrupulous TV producers are naturally loath to repeat the experience so they should be helped to recognise good practice, and this holds true too for university communications departments which often wish to promote academics’ work.

without setting them up for exploitation.

Universities have only gains to make when they understand the potential for public engagement which television documentary offers. They can welcome the media’s disciplined involvement in their endeavours and take initiatives to present their priorities. The role of the media in Research Impact Assessment is another important area.

The medium’s capacity

I’ll end by returning to a question raised at the start, about narrative. There is a limit to what a television documentary can contain without collapsing into incoherence. Sometimes historians demand from this medium a piling-on of information without regard for the image system that has been built up within a programme or for the pace established. But neither is the simultaneity of TV documentary sufficiently appreciated. It is a medium in which many things happen at once. There is much more going on than the delivery of facts or points of view. Narrative (including contested narrative), image, soundtrack, colour, and more, all work together towards the beauty appropriate to this medium. This is the totality to which viewers respond. Poor television arouses emotion, entrances and intrigues in irresponsible ways, with heavy-handed sign-pointing and insufficient self-awareness. Good television can, while offering narrative, counterpoint or inflect that narrative in ways the audience is able to read. The setting of a Piece To Camera or choice of shot size ‘speak’ as effectively as commentary or interview. The audience enjoys the experience of learning in this way which invites their collaboration and is not passive.

The more television producers and historians reflect together on their aims and practice the better, because good history on good television is a good thing.

The Story of Wales, produced by independent production company Green Bay Media, was broadcast on BBC 1 Wales in Spring 2012 and is expected on BBC 2 Network in early October.

AngelaGraham2003@aol.com