Melissa Baird Blog

Melissa Baird is a PhD researcher at QUB studying Irish America and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Movement, and the curator of “1922 – 1972 – 2022: Years of Chaos and Hope” at the Linen Hall Library.

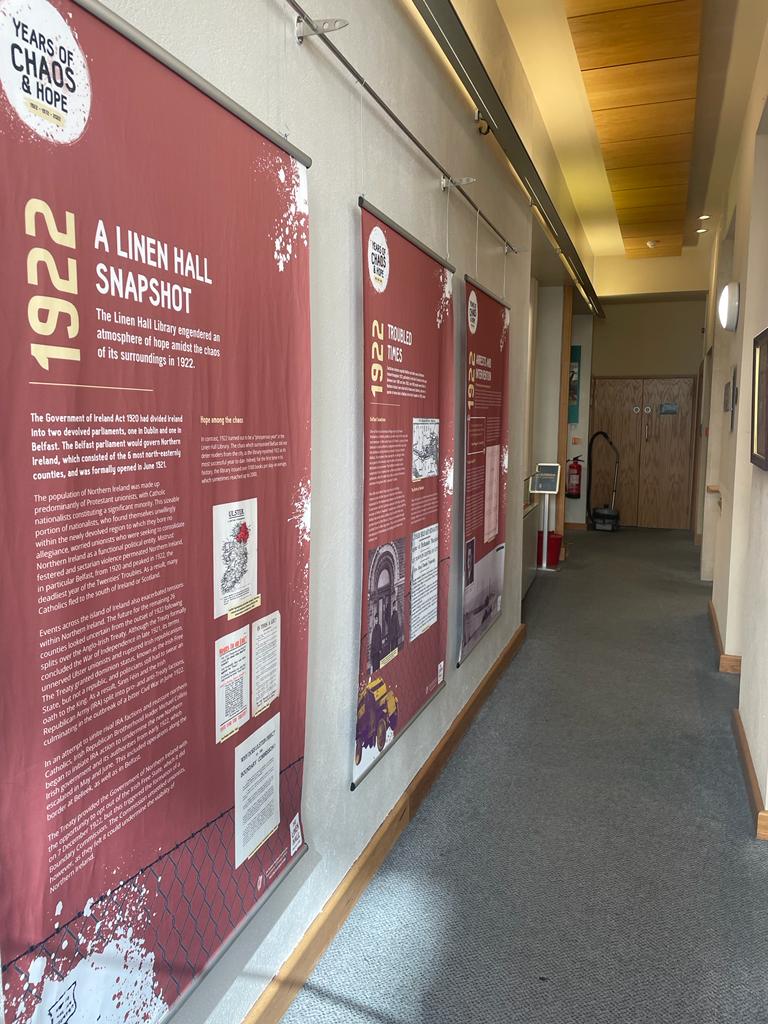

Years of Chaos and Hope was my first ever major exhibition, though I had organised some one-day poster exhibitions and academic conferences. To add further pressure, this exhibition was for the Linen Hall Library, one of the most treasured libraries and museums on the island of Ireland, whose renowned Northern Ireland Political Collection attracts scholars from across the world.

The Linen Hall Library’s reputation is one of being a shared, inclusive space – demonstrated most clearly through its permanent display of political posters from almost every point of view in the Northern Irish conflict. This was just one example of how the Linen Hall carves out a rare space for us not to shy away from our history in our attempts at reconciliation, but rather lay in all out to bare, so we can at least see multiple perspectives, even if we do not agree with them.

It was with this in mind that I tackled the exhibition. The brief was an exhibition to explore 1922 and 1972, the two bloodiest years in the 1920s troubles and our more recent conflict. Taking the lead from previous exhibitions, I decided to use the Linen Hall and its archives as my framework to showcase these years.

And so, I began step one of exhibition planning: trawling through the archive.

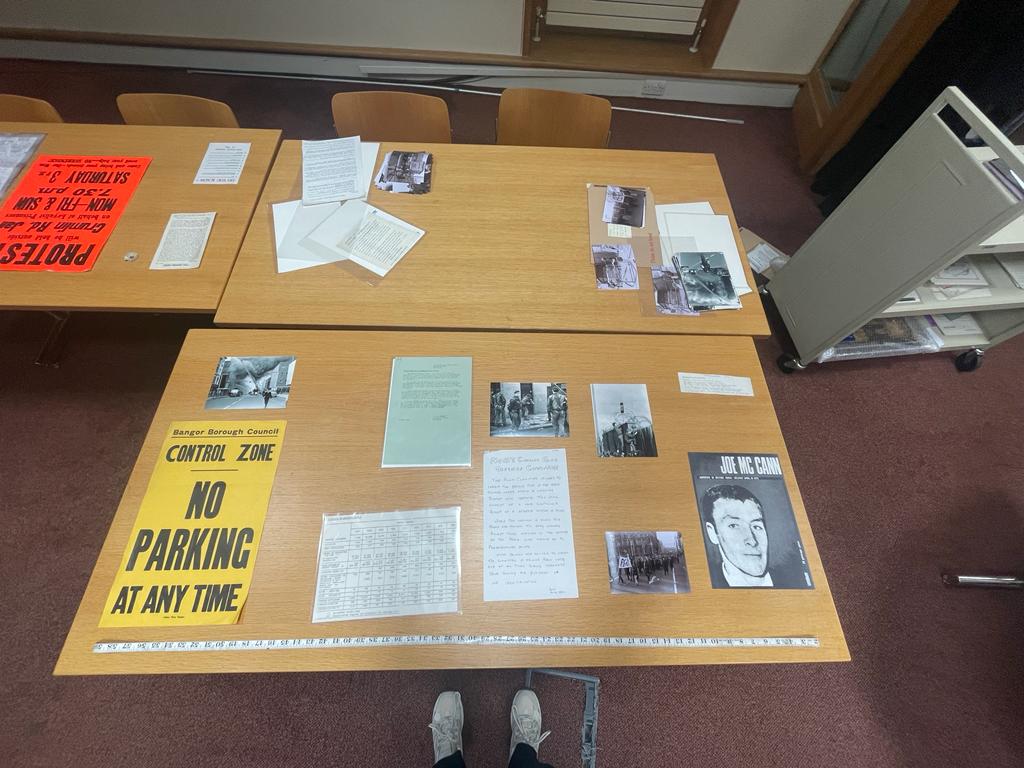

The Linen Hall’s diverse archive gave me a wide vantage point to delve into 1922 and 1972 from as an objective view as possible. The breadth of the archive meant that most of the main issues were well-documented, and I could rely almost entirely on the library’s collections to showcase both these years. Then I began to realise I was developing a problem that I had never came across in my own research: I had too much material.

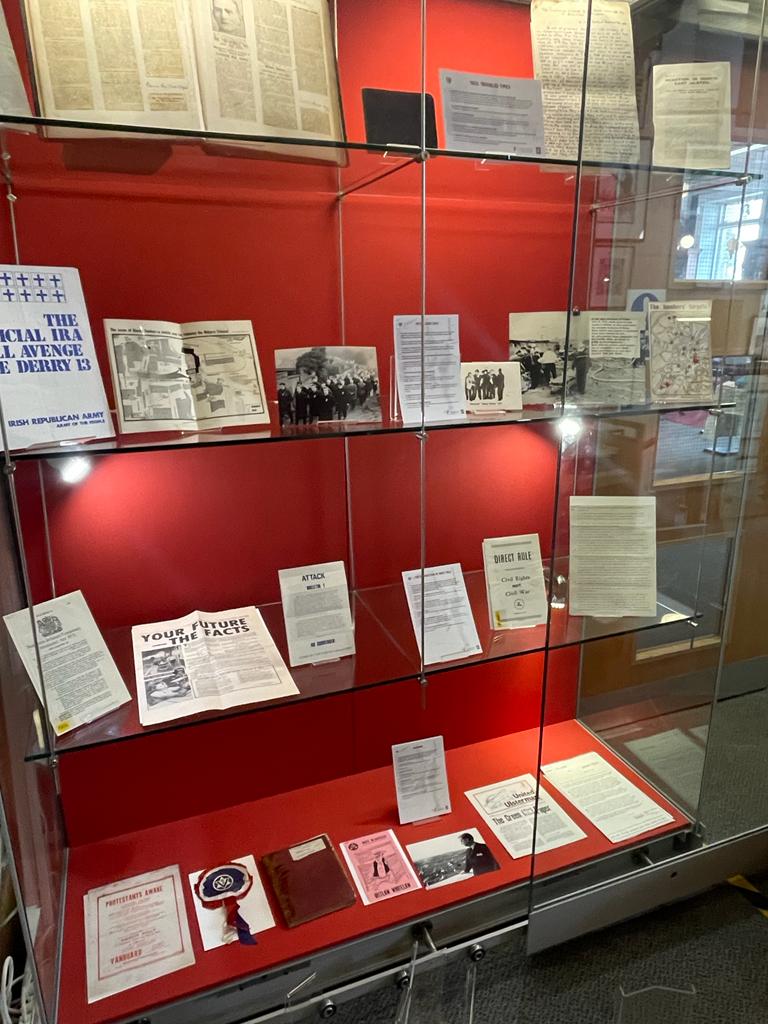

In almost every archive I have visited for my PhD research, I have encountered the familiar nightmare of waiting at my reading desk for my big, bulky, treasure-trove of documents to be brought out, only for a thin sliver of a file to be placed flatly in front of me. I am used to scurrying around looking for other sources, not trying to limit them. But within the archives of the Northern Ireland Political Collection there are so many different artefacts in relation to 1972 in particular that I needed to focus in on themes shared between then and 1922.

Step two: selecting themes

From my own research, I was aware of the significant events of 1972: Bloody Sunday, Bloody Friday, the imposition of Direct Rule, and the escalating opposition to internment. I was vaguely aware of the key issues in 1922: sectarian violence in the north, the split in Irish Republicanism over the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the introduction of the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act. Aside from that, I was very conscious that what united 1922 and 1972 was that they represented the peak years of violence in their respective eras of trouble. In the first six months of 1922 over 150 people died as a result of political violence in Belfast alone, while 1972 was the year of the highest number of casualties throughout the three decades of political conflict known now as the Troubles. From this I had a lot of information to cover so I began to structure the information around three key themes for both years: the Linen Hall snapshot, the troubles times, and the arrests and interventions.

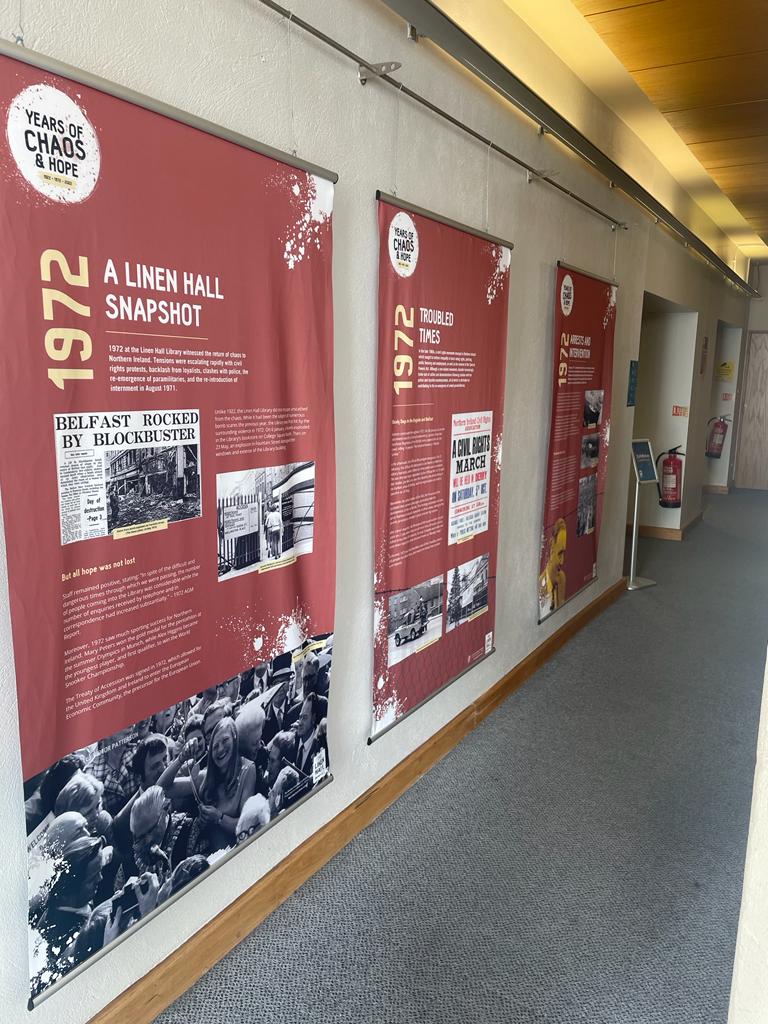

Theme 1: The Linen Hall Snapshot

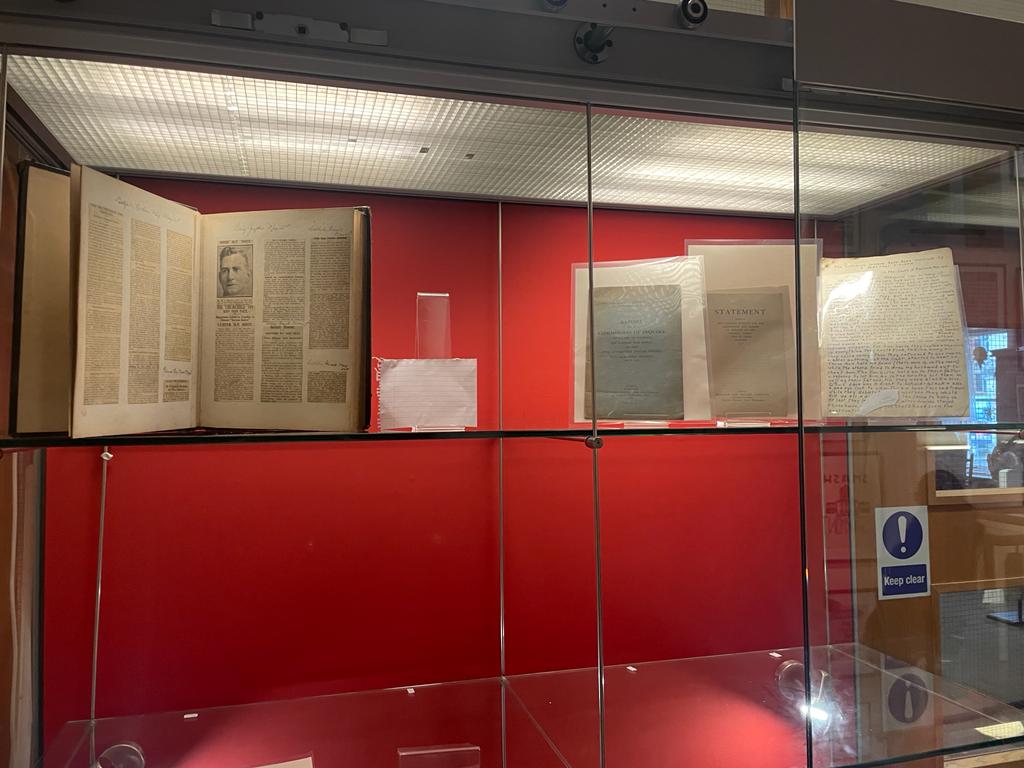

It was necessary to include some broad context to the years of 1922 and 1972, plus some insights into what was going on within the Linen Hall Library at the time, so for this I decided to call this section the Linen Hall Snapshot. For 1922, I wanted to give a glimpse of what was happening on the island of Ireland, as well as the ramifications of the hardening border across it. This gave me the opportunity to showcase the numerous items we hold from the Irish Civil War, including a photo of National Army Leader Michael Collins lying in state following his death on this very day 100 years ago (22nd August 1922). We also have various publications from groups from either side of the Treaty divide, as well as pamphlets from religious groups advocating for peace. We also have on display artefacts relating to northern republicans, such as Hugh Magee from Cushendun, County Antrim, and the County Tyrone-born, anti-Treaty IRA leader, Joseph McKelvey.

For 1972, the Linen Hall snapshot was my chance to sneak in some areas of hope in an otherwise dreadful year. Alongside the escalation of intercommunal tensions in Northern Ireland, sports stars like Mary Peters brought some much-needed relief when she won her gold medal at the Munich Olympics in September 1972, of which we held plenty of photos in our archive. Thus, by giving the Linen Hall’s perspectives first, I could give an overview of key issues, plus showcase some of our important holdings which did not fit neatly into our other themes.

Theme 2: Troubled Times

As mentioned before, 1922 and 1972 were marked by the highest levels of violence from their respective times. In 1922, tit-for-tat killings were common, with civilians like the McMahon family and catholic girls playing in Weaver Street being killed almost certainly in retaliation for IRA attacks. One such attack which prompted a fierce response from the Northern Irish government was the IRA assassination of Unionist M.P. William Twaddell on 22 May in Belfast city centre. Twaddell’s murder led to the implementation of widespread internment without trial that very night. The media’s reaction to Twaddell’s murder was well-documented in a large scrapbook of newspaper clippings I found in the Linen Hall archives, alongside a plethora of printed material from catholic clergy and sympathisers complaining about the treatment of Catholics and nationalists in Northern Ireland.

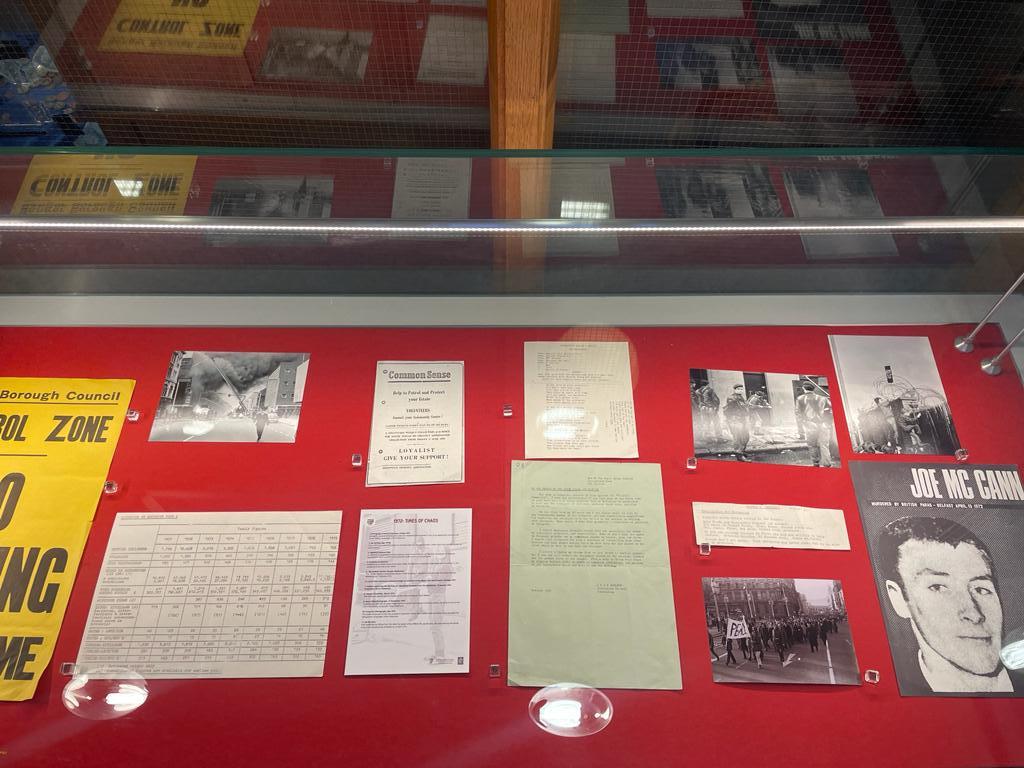

Meanwhile in 1972, troubled times had returned to Northern Ireland following the backlash to the civil rights movement, which contributed to groups like the IRA rearming, and the development of loyalist paramilitaries like the Ulster Defence Association. 1972 encapsulated two of the bloodiest days in Northern Ireland’s history: Bloody Sunday and Bloody Friday. Bloody Sunday was on 30 January when soldiers from the Parachute Regiment of the British Army opened fire on an anti-internment march in the Bogside area of Derry/Londonderry, killing 14 people. The reaction to Bloody Sunday was intense, and the subsequent inquiries which basically exonerated the British Army provoked further outrage from nationalists and republicans. There has been extensive material produced about Bloody Sunday, its legacy and commemoration, and the archives of Linen Hall alone contains stickers, posters, postcards, and photographs amongst many others about the massacre. On Bloody Friday, which was 21 July, the IRA set off over 20 bombs in under 90 minutes, killing 9 people and injuring many more. Unlike Bloody Sunday, however, there was little produced about the day or even to commemorate it, apart from pamphlets of condemnation from the Northern Ireland Office.

Theme 3: Arrests and Intervention

The third theme was the clearest to me from the beginning. One of the first items I picked up in the archive was a folder labelled “correspondence from the prison ship Argenta.” HMS Argenta was the prison ship the Northern Irish government had to purchase in their scramble to house the booming prison population as a result of their implementation of internment without trial. On the night of 22 May 1922, authorities picked up over 200 men. At that time, Northern Ireland only had three jails at its disposal: Derry/Londonderry, Armagh and Belfast. Consequently, the government purchased the Argenta, a former American cargo ship and transformed it into a prison facility, and likewise with their acquisition of the Larne workhouse.

Internment without trial had been made legal under the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act, which was passed on 7 April 1922. The act gave civil authorities sweeping powers such as to introduce curfews and impose restrictions on licenced premises. Although initially enacted as a temporary measure, the Special Powers Act remained in place for over 50 years. Unionist politicians argued that it was necessary to restore law and order to Northern Ireland, particularly the threat from the IRA. For nationalists, however, the Special Powers Act reaffirmed unionist dominance in Northern Ireland. Its continuance and almost exclusive use on the Catholic minority population formed a major part of nationalist resentment towards the Government of Northern Ireland.

Thus, fast forward to the early 1970s, and the Special Powers Act continued to form the basis of nationalist agitation against the government, exacerbated by the decision to re-introduce internment in August 1971. By 1972, opposition to internment had overtaken all other civil rights demands, which was clear from the archives at the Linen Hall, as many of the posters and political publications from this time were in protest to the measure.

After internment had failed to curb the violence, and especially after Bloody Sunday, the UK government intervened. On 24 March, UK Prime Minister Ted Heath announced that Westminster would be “assuming full and direct responsibility for the administration of Northern Ireland until a political solution to the problems of the province can be worked out.” Heath then assigned Northern Ireland a Secretary of State, William Whitelaw. Whitelaw introduced the Northern Ireland (Temporary Provisions) Act 1972, which suspended the Stormont Government from 30 March and transferred all powers to Westminster.

Like the Special Powers Act, Direct Rule was enacted as a temporary measure for 12 months. However, except for a brief period in 1974, Northern Ireland remained under Direct Rule until the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, which paved the way for the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Step Three: Panic about the Public

At this stage, I had the artefacts selected and I had all this information roughly drafted into sections, but the lingering concerns about the public’s reaction started to amplify. Trying to recreate shared historical narratives is difficult in any setting, but in an area with such a contentious and contested past, and particularly in years as pivotal as 1922 and 1972, there were extra concerns. These were dark times for the people of Northern Ireland, and I was aware that many visitors might have vivid memories, unique to them, which may not be totally reflected in the items on display in the exhibition.

I also stressed about how I wrote the text for the display panels. I tried to leave the interpretation as much in the reader’s hands as possible, which I suspect is the main problem for historians whose academic training teaches the opposite. I rationalised that the exhibition was not intended to be an extensive investigation into the whys of 1922 and 1972, nor was it supposed to represent a universal experience, for that simply does not exist. As a result, I emphasised that the exhibition gives an insight from multiple and sometimes conflicting viewpoints, as found in the Linen Hall’s archives, and more importantly, across the society in which we live.

Finally, I will end on the lessons I’ve learned from my first real exhibition:

- Be cognizant of the people, and their sensitivities connected to the history about which you are exploring

- Let the above influence how you present information but do not let it dictate it either

- Realise that a shared history does not necessarily mean one that everyone agrees on, but rather a representation of issues that affected most if not all sections of society

- Make sure everything fits in your cabinets before the exhibition launch day!