Shannon Devlin Blog

Queen's First Women

Dr Shannon Devlin

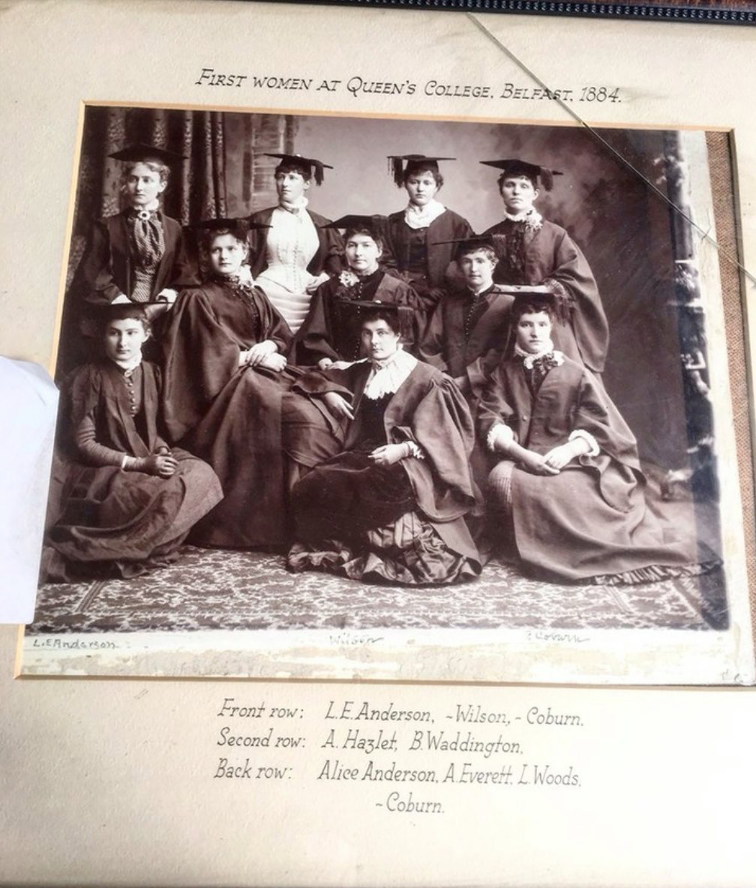

October 2022 marks 140 years since Queen’s College, Belfast (now Queen’s University, Belfast) became the first university in Ireland to admit women to classes. The nineteenth century witnessed rapid change in the push for more opportunities for women in education. The setting up of the Royal University of Ireland (RUI) in 1880 allowed women to matriculate and gain degrees on the same basis as men, preparing either at home or at liberal collegiate schools such as the co-educational Methodist College or Ladies’ Collegiate, Belfast (later Victoria College).[1] Spurred on by the RUI legislation, educational campaigners involved in the Belfast Ladies’ Institute, such as Isabella Tod, lobbied Queen’s College, Belfast (QCB) to admit women, stating it was unfair that they did not have the same access to professors – who wrote the RUI examinations – as male students. In 1882, Rev. J. L. Porter, President of QCB, received a petition from ‘influential persons in and around Belfast’ and the Senate finally admitted women to arts classes in 1882, science classes in 1883, and medical classes in 1889. The first nine women (the ‘Nine Graces’) graduated from the RUI in 1884 but it would be a further year before women attached to QCB joined their pioneering ranks. A recently unearthed photograph depicts some of the first women at Queen’s. Keen eyes on social media noted that only nine of the ten women were named (and further research proved that one of these names was wrong).

Crowdsourcing historical mysteries has become a popular pastime for many people on social media. #Twitterstorians and #AncestryHour hashtags on Twitter teem with tips for solving historical riddles. The National Library of Ireland has a regular group of ‘Photo Detectives’ who have been quietly filling in the gaps in the NLI catalogue on their Flickr page. The sleuthing in the comment section became so comprehensive that the NLI turned the findings into an exhibition in 2017. Trawling online forums, scouring Google Maps, or wading through Census records in the pursuit of an elusive puzzle piece has become part and parcel of historical research for amateurs and professionals alike. Funded by subscriptions from the general public, websites like Ancestry and FindMyPast are revolutionising how record collections are digitised for global access by millions of people every year. Historians like Jerome de Groot and Tanya Evans have been grappling with how this reciprocal process can be helpful for both academic historians and wider public history audiences. Genealogy can promote archival collections and museum exhibitions to a vast audience. On the other hand, the popularity of genealogy has allowed social historians access to digitised, searchable databases that previously remained in static archives.

'First women at Queen's College, Belfast, 1884'.

This picture was discovered during the renovations to the Queen's Students' Union in 2019.

Evidence suggests this picture was taken in 1886, the same day of the famed photograph of QCB graduates outside the Lanyon Building.

Some of the women, in the same clothing, can be seen in both photographs.

The First Women at QCB

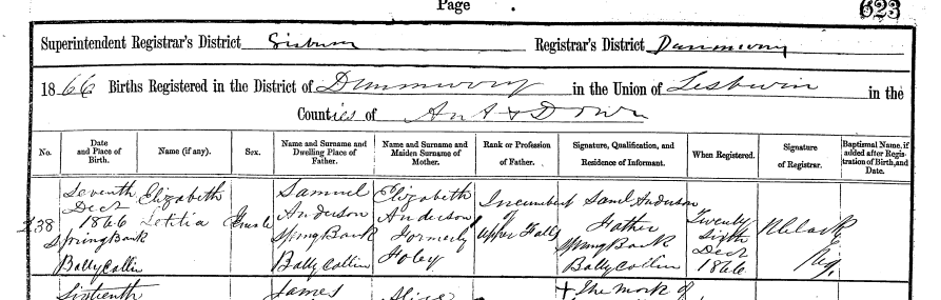

Tracing women through the historical record can be notoriously difficult. Naming conventions in news reports or other biographical documents usually referred to women as ‘Miss’ or once they had married, by their husband’s name. The Calendars for Queen’s College, Belfast list everyone who attended as registered students in each academic year, which is a helpful starting point. All ten women appear in these lists during the period 1882-87. Most of the women were born just before the legal requirement to register births but looking for younger siblings can help flesh out details of their family background and provide clues in determining the previous generation of the family tree.

Birth registration of L. E. Anderson, 7 Dec. 1866.

The registration tells us her family address, her father’s profession and her mother’s maiden name.

Unusual surnames or the inclusion of middle names help identify individuals across the historical record. Using genealogical methods, we can deduce that the women are:

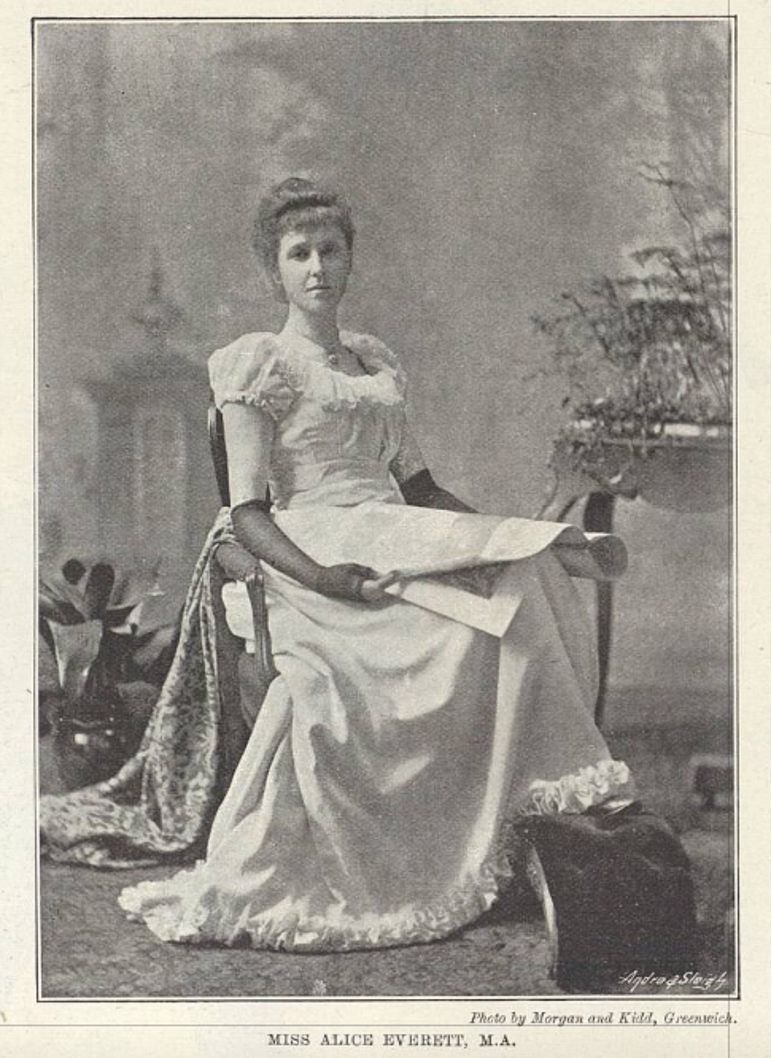

Back row: Alice Anderson (1863-98), BA 1886; Alice Everett (1865-1949), BA 1887; MA 1889; Louisa Jane ‘Louie’ Wood (1863-1956), BA 1887; Helena Coburn (1863-98), BA 1886.

Middle row: [Florence ‘Flora’ Augusta Hamilton (1862-1908), BA 1886]; Annie Woods Haslett (1863-1939), BA 1885, MA 1887; [Letitia Alice Walkington (1854-1918), BA 1885, MA 1886, LLB 1888, LLD 1889].

Front row: Letitia Elizabeth Anderson (1866-1965), Mary Wilson, BA 1887; Sara Coburn (1864-1918), BA 1885.

However, people with very common names cannot be traced. For example, 251 Irish ‘Mary Wilsons’ were born in the period 1864-70 – too many to trace – and this number does not include any Mary Wilson born before birth registration was introduced in 1864, those Marys who were incorrectly registered, or Wilsons born outside of Ireland. This means that this particular Mary Wilson is unfortunately lost within the historical record. (If you know more about her, please drop me an email!)

The middle row is the main mystery of the photograph. First of all, attempts to trace ‘B Waddington’ were futile. No student under that name is listed as matriculating in the RUI and there appears to be little trace of any Waddington families in Ireland at this time. Creating hypothetical connections is a key method in building a family tree in order to piece together enough evidence to be sure you have the correct individual. The only Waddington deaths registered in Ireland belong to a couple who died in the Belfast Workhouse – not where you would expect the parents of a well-educated, middle-class woman to appear – and their children were too young attend university in the 1880s.

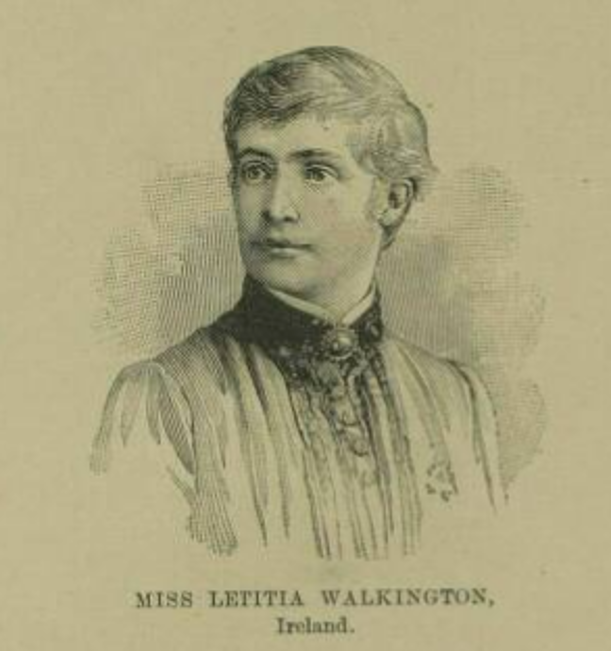

At a dead end, I turned to look for our missing student. A number of other names continually pop up in exam lists or news reports of student successes at QCB. One of these names was Letitia Alice Walkington (1854-1918). A pioneer in the Irish law profession, Letitia has her own Wikipedia page and, crucially, was profiled by the London Illustrated Press, providing us with a sketch to compare.

London Illustrated News, 13 Nov. 1897.

Convinced Walkington was in fact ‘B Waddington’ in the middle row, I turned to some of the other names attached to Queen’s at this time. Two other women graduated from QCB with their B.A. in 1886. Martha Kerrison Lynn (1865-1948), originally from Sligo, attended Belfast Ladies’ Collegiate before joining QCB briefly and completing her B.A. in ’86 through ‘private study’. She returned in 1890 to study for her M.A. The second was Florence Augusta Hamilton (1862-1908), who excelled in mathematics throughout her education, winning a number of valuable prizes and scholarships at Methodist College before graduating with her B.A. in ‘86 at QCB. By a stroke of luck, there were a number of photographs of Florence to compare to the group shot and I suggest that she is sitting on the left in the middle row (although, happy to take opinions on this!)

Florence Augusta Hamilton (1862-1908). Wikimedia Commons.

So who were they?

All of the women pictured were from the Ulster middle classes. Only two were not born in Ulster: Alice Everett was born in Glasgow but came with her father to Belfast when he took up a position as professor at Queen’s and Louie Wood was born in Co. Longford but had moved to Magherafelt as a child with her father’s ministry. All were Protestant reflecting the wider religious demographic of the Ulster middle classes and of Queen’s at this time – the Andersons, Everett, Hamilton, and Walkington were Anglican; the Coburn sisters and Haslett were Presbyterian; and Louie Wood was Methodist. In fact, four of the women were children of clergymen: Florence Hamilton’s father was rector at St Mark’s, Dundela; the Anderson sisters’ father was vicar of Upper Falls (Dunmurry); and Louie Wood’s father, a Methodist minister in Magherafelt. Alice Everett’s father was a professor at Queen’s, Sara and Helena Coburn’s family were seed merchants at Banbridge, Letitia Walkington’s father a lard merchant of Strandtown, and Annie Woods Haslett’s father a draper in Rathfriland.

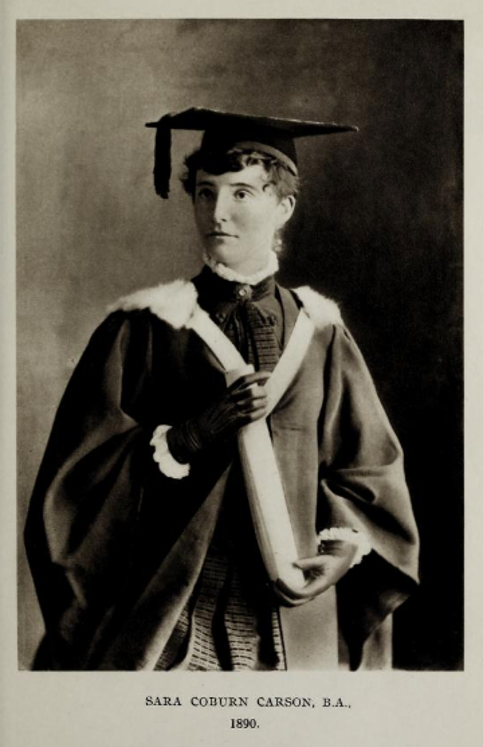

Sara Coburn, B.A. This portrait was found in her husband’s memoir, James Carson, Carsons of Monaghan and Ballybay (Lisburn, 1931).

Despite being dated 1890, it was probably taken on the same day as the group photograph.

Young women in the middle classes had the ability to devote time and money to studying in further education. This first cohort benefitted directly from the introduction of the Intermediate Education Act in 1878, all featuring prominently in prize lists in the period before they joined Queen’s. Most of the women also had other siblings in education at the same time – six Anderson siblings would eventually pass through QCB, three Haslett siblings attended concurrently with two other sisters at nearby Victoria College, and at least four Wood siblings attended QCB. Feeling the financial pinch, the education of brothers might be prioritised by parents with sisters or younger siblings receiving a short stint of schooling or expected to learn from older siblings. This was precisely why scholarships, prizes, and exhibitions for academic excellence were important for young academic women.

Porter claimed that the first female students settled into life at Queen’s well attending the same classes and experiencing university life just like their male counterparts (except for having to endure some of the men showing off…). However a problem was immediately clear following the first exam session. Whilst women could participate in the College competitions, they could not win the monetary prizes like their fellow male students. In 1884, Alice Everett won first place in the science First University Examination and Florence Hamilton placed fourth in the science Second University Examination. Neither were allowed the prize attached to their position due to their gender.

Not having anticipated women to achieve prize positions, President Porter was forced to take the advice of the Attorney-General of Ireland whose (rather flimsy) excuse was that the statute of the university did not stipulate a student could be female. This crucial wording had to be changed by Queen Victoria herself. Over the next decade, QCB women continued to win and be refused QCB prizes. In 1889, Thomas Hamilton, who had taken over as President, argued strongly that this rule was the reason QCB still had relatively low numbers of women in the college: ‘there seems to be no good reason why, if ladies have the ability to gain our honours, they should be forbidden to enjoy them’.[2] And he was right – many bright young women would go to other colleges where they could win prizes – Alice Everett won a £42-a-year for three years scholarship to Girton College, Cambridge, where she finished her B.A. and completed the mathematics tripos MA; Annie Woods Haslett won an RUI scholarship of £20 and returned to Victoria College on a John Brown Shaw Scholarship to study her M.A.; Mary Wilson placed first in her English and modern literature exams for the second year running, winning the Henry Hutchinson Stewart Scholarship worth £30-a-year for three years in 1887. Finally, after 14 years, the statute was changed in October 1896. Hamilton remarked that this would again change the nature of competition within the College, failing to see that women had been competing – and winning – the entire time the prize was refused to them.

Alice Everett’s profile in The Sketch, 22 Nov. 1893

After Queen’s

These ten women represent a fraction of the 45 women who attended QCB in the period 1882-90. All women completed their degrees at different times and most did so with a combination of classes at QCB and other schools, especially nearby Methodist College and Victoria College. Sara Coburn, Annie Haslett, and Letitia Walkington were the first to graduate in 1885 with their B.A. degree. They were followed by Alice Anderson, Helena Coburn, and Florence Hamilton in 1886, and Mary Wilson, Alice Everett and Louisa Wood in 1887. Despite attending QCB as a non-matriculated student in 1884 and matriculating the following year, Letitia Elizabeth Anderson appears to be the only woman featured in the photograph to not complete her degree.

Two of the women in this photograph went on to have particularly pioneering careers. As mentioned, Letitia Walkington became the first woman in Ireland or Great Britain to attain a law doctorate (the second, Frances Gray, was also a QCB grad). However, she recognised that she would not be called to the bar due to her gender and devoted her life instead to the ‘welfare of women and children’. A member of the Irish Women’s Suffrage and Local Government Association, she co-founded the Belfast Women’s Suffrage Society in 1912 where she acted as Vice-President. In 1918, she formed the Women Voters’ Union in Belfast to unite women workers but she died unexpectedly the same year before this could come into fruition. Alice Everett similarly was a pioneer in her profession. After completing her MA at Cambridge and a brief term at art school, Everett was invited to become the first female observer at the Greenwich Observatory where she operated a telescope and mapped stars. In 1895, she became the first woman to work at a German observatory and later went on to be a founding member of the Royal Television Society, pioneering television technology in the 1920s and 30s.

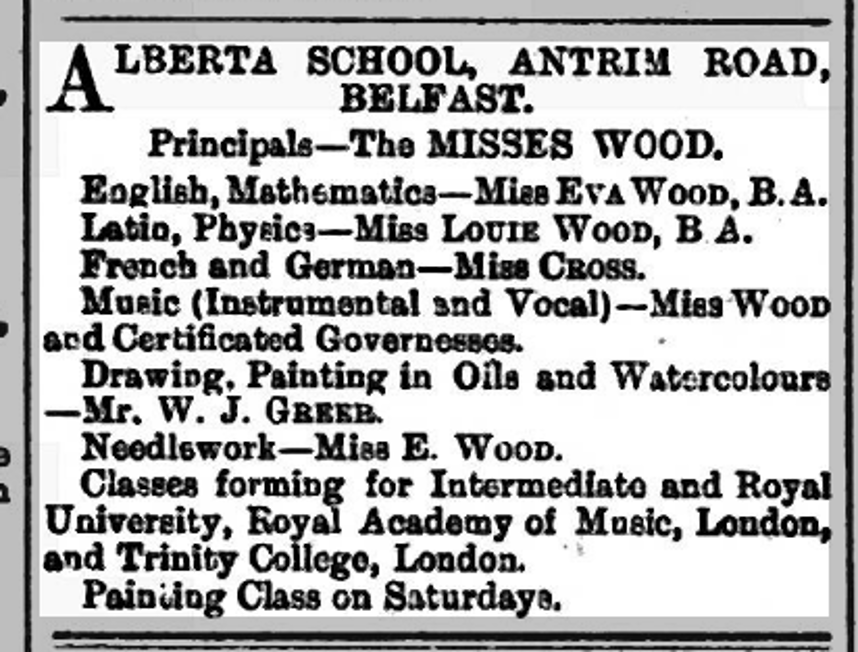

Many of the other women also had successful independent careers. Viewed as one of few acceptable professions for middle-class women, teaching was the most obvious route for many women with academic qualifications. (In 1893, Alice Everett commented that this was a ‘universal drift’ she was adamant not to follow). After a stint teaching at Victoria College, Annie Woods Haslett taught languages in her brother’s academy in Dublin. Martha Kerrison Lynn went to England as a governess. Louie Wood and her sister, Eva (QCB BA 1888) ran a school from their house on the Antrim Road offering support for those who wished to complete the RUI examinations.

Advertisement for Louie and Eva Wood’s school at their home, Alberta on the Antrim Road.

Northern Whig, 24 Oct. 1888.

After her sister’s death in 1890, Louie Wood gave up her school and married, moving to England. Despite stretching nineteenth-century middle-class social boundaries, some Victorian stereotypes still remained and it was deemed inappropriate for married women to work. The unmarried Anderson sisters acted as housekeepers for their brother who was a Professor of Logic in Sheffield. Florence Hamilton married and turned to encouraging the academic achievements of her children, which included the author C. S. Lewis. The Coburn sisters married a set of brothers from Monaghan and exhibited their leadership skills in philanthropic circles, participating in Zenana Mission fundraising and non-militant suffrage activity. Sara Coburn was noted to be a keen debater and both sisters’ B.A. degrees are inscribed on their headstone in Ballybay Graveyard, hinting at how much they valued the achievement of attaining their degrees. No matter their path after Queen’s, all of the first women to attend pushed for educational reform for those coming after them.

Historians who view family history sleuthing as ‘just’ a hobby have a lot of learn from keen genealogists. This approach can provide insight into the lived experiences of people in the past and is particularly helpful in filling in gaps where other records no longer survive. Biographical material, migration records, testamentary material, gravestone inscriptions, and personal memoirs allow historians to piece together both micro- and macro-histories revolutionising how we can explore and understand the past.

The information for this blog was derived from a number of sources including: the Census of Ireland, 1901 & 1911; the Census of England, 1891, 1901 & 1911 (digitised by Ancestry); Irish civil registrations of births, marriages, & deaths (digitised by the GROI); the Irish newspaper collection, the Sketch & Illustrated London News (digitised by the British Newspaper Archive); PRONI digitised will and probate collection; President Reports of Queen’s College Belfast, 1884-90 (digitised here); and the QCB Calendars, 1883-90 (held in the Queen’s University Archive, with thanks to Ursula Mitchel).

See also:

TW Moody and JC Beckett, Queen's Belfast, 1845-1949: the history of a university (Faber, 1959).

Aoife O’Leary McNeice, ‘Bored bluestockings and frivolous flirts: dynamics of gender and the experiences of the first female students of Queen’s College Cork, 1879-1910’ in Irish Studies Review, 28, no. 4 (2020), pp 446-50.

[1] Attendance at an approved university or college was not required until the University (Ireland) Act, 1908.

[2] QCB President’s Report, 1888-89.